(english text below)

A grande richiesta, abbiamo deciso di pubblicare sul sito le lunghe e straordinarie interviste apparse sul magazine cartaceo dal 2009 al 2011. Quaranta trascinanti conversazioni con i protagonisti dell’arte contemporanea, del design e dell’architettura. Una volta alla settimana, un appuntamento da non perdere. Un regalo.

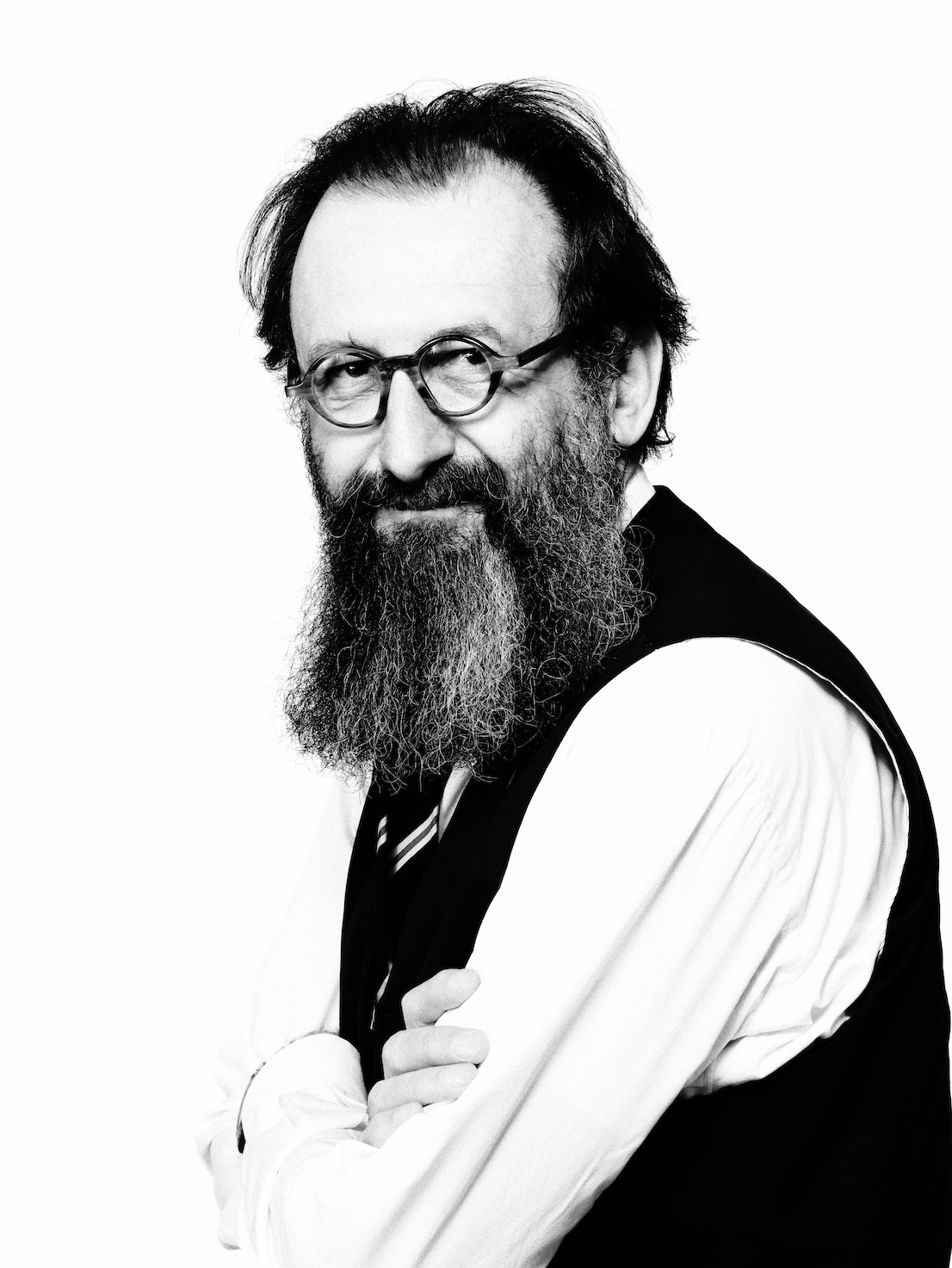

Oggi tocca a Stefano Boeri.

Paolo Priolo

Intervista di Pietro Los. Klat #01, inverno 2009-2010.

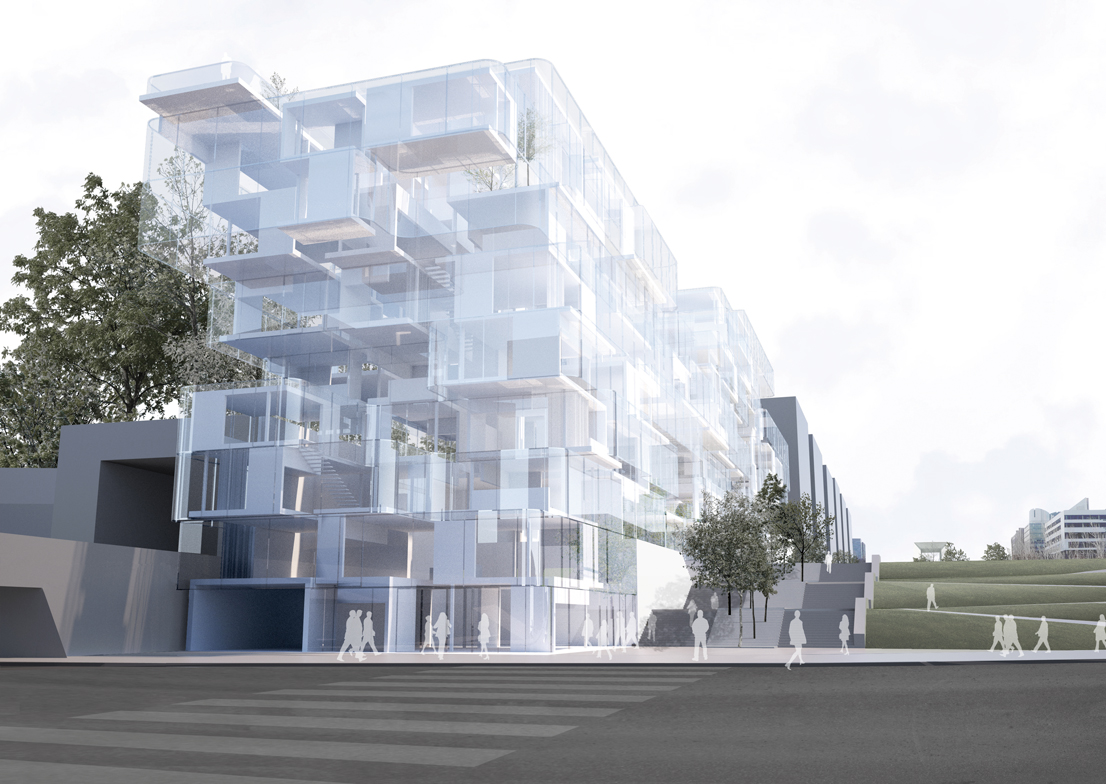

Protagonista della scena architettonica internazionale, progettista critico e innovativo, fondatore dell’agenzia di ricerca Multiplicity e direttore di Abitare, Stefano Boeri ha da poco concluso il suo intervento di riqualificazione dell’ex area militare alla Maddalena e ha ripreso i lavori di un’importante architettura-darsena a Marsiglia. Nel frattempo, si dedica al perfezionamento del suo Bosco Verticale a Milano, potente modello di residenza sperimentale. KLAT ha fatto il punto con lui, alternando teoria e prassi, pensiero e progetto.

Come è cambiata e come sta cambiando la professione di architetto negli ultimi anni?

Non è cambiata molto, se guardiamo alla sostanza. Nella nostra professione, pulsano da sempre due dimensioni: una che tende a includere il mondo esterno e una che tende invece a escluderlo. Mi spiego meglio: la dimensione inclusiva, analitica, è quella che ci spinge di continuo verso una specie di bulimia informativa: fare l’architetto significa infatti raccogliere continuamente idee, informazioni, opinioni, intenzioni sul contesto su cui si deve operare, sui suoi utenti, sui materiali da usare. È un modo di includere il mondo, che ci aiuta a immaginare il futuro di un luogo, a riempirlo di visioni e di possibilità evolutive. Accanto a questa dimensione, ce n’è sempre un’altra, opposta, necessariamente esclusiva, basata su un processo crescente di selezione di possibilità. È quella che ci spinge verso la definizione di una forma finale, compiuta e individuale: la forma definitiva e unica con cui decidiamo di plasmare un pezzo di città, un edificio, un oggetto di design. Quando progettiamo, dobbiamo riuscire a far convivere l’opportunità di un sapere analitico, che si apre al mondo, con la necessità di un sapere che invece esclude il mondo, tranne che per quella piccolissima parte che riguarda la nostra attività di progettisti. Come ben sappiamo, la relazione tra queste due dimensioni, che richiama quella tra analisi e progetto, è complessa e spesso conflittuale, ma costituisce la cifra della professione dell’architetto. Al punto che la specificità di ogni architetto si gioca tutta dentro questo rapporto.

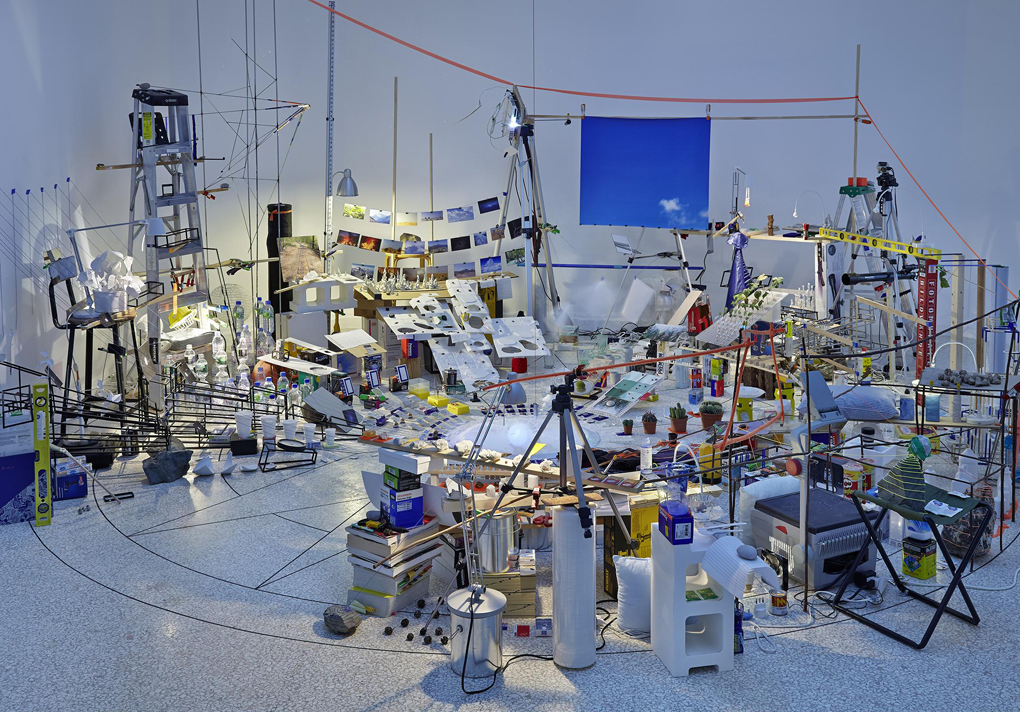

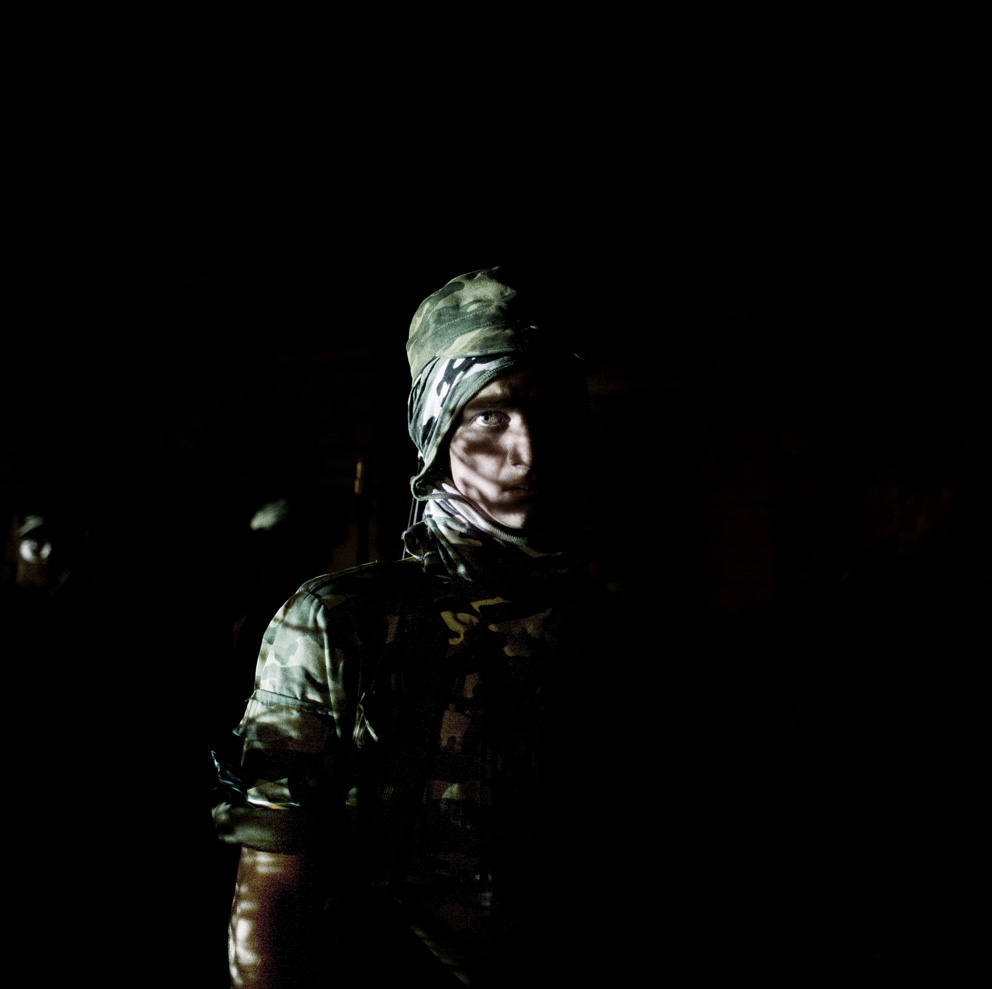

![Stefano Boeri, Gianandrea Barreca, Giovanni La Varra, Bosco Verticale, 2008. Rendering Boeri Studio, Milano]()

Stefano Boeri, Gianandrea Barreca, Giovanni La Varra, Bosco Verticale, 2008. Rendering Boeri Studio, Milano

Nel suo caso?

Per quanto mi riguarda, penso che questo rapporto diventi interessante quando si riesce a mantenere una sostanziale autonomia tra le due dimensioni, evitando che una prevalga sull’altra, che una si sviluppi prima o in assenza dell’altra. Entrambe vanno invece vissute in autonomia e simultaneamente, lasciando che dal loro conflitto e dal loro attrito si generino delle associazioni improvvise, dei significati imprevisti, nuove idee. Io non ho mai creduto al primato logico o temporale dell’analisi sul progetto e neppure al suo opposto. Credo, invece, che si debba imparare a governare l’inevitabile conflittualità tra le due sfere. Gli architetti schizofrenici sono i più interessanti.

È stato direttore di Domus dal 2004 al 2007, e dal 2007 dirige il mensile Abitare. Che funzione può o deve svolgere una rivista specializzata rispetto all’architettura?

Ogni rivista di architettura definisce la propria identità a partire dal rapporto che stabilisce tra gli edifici di pietra e quelli di carta. Cioè, a partire dal modo in cui cerca di colmare il vuoto tra l’esperienza sensoriale di un’architettura che esiste come materia, in qualche parte del mondo esterno, e l’esperienza intellettuale della stessa architettura, che si replica come simulacro nella nostra immaginazione di lettori. Il senso ultimo di riviste come Abitare è quello di pubblicare architetture che il lettore raramente visiterà, abiterà o toccherà, e che potrà abitare solo attraverso l’immaginario estetico e simbolico che la rivista produce. Il rapporto tra la natura fisica e la natura simbolica di un luogo è dunque molto delicato. Negli ultimi anni, abbiamo assistito a un crescente sdoppiamento d’identità dell’architettura. Le grandi architetture, oggi, hanno una vita doppia e parallela. Ci sono edifici divenuti celebri, anche grazie alla diffusione da parte dei media globali, che da un lato conservano, in qualche parte del mondo, una loro identità fisica, materiale. Dall’altro, invece, potenziano a tal punto la loro identità simbolica e immateriale da diventare veri e propri simulacri, autonomi rispetto all’originale. A volte, queste due modalità di esistenza non sono neppure legate da meccanismi di causa-effetto: alcune architetture continuano a circolare come immagini di culto nella semiosfera, anche quando la loro vita di edifici materiali ha perso smalto e attrattiva.

Come si colloca Abitare rispetto a questi due mondi?

Abbiamo cercato di aiutare il lettore a ridurre la distanza che separa i simulacri dagli edifici materiali, alternando rigore e creatività. Alla descrizione rigorosa (fotografica, topografica) di un’architettura, affianchiamo interpretazioni ricche di fantasia e dichiaratamente arbitrarie dei luoghi e degli spazi. Non credo alla fedeltà descrittiva come principio guida di una rivista, alla corrispondenza univoca fra realtà materiale e rappresentazione. Penso sia necessario proporre punti di vista diversi, pure interpretazioni della realtà, mondi paralleli capaci di dare un senso aggiuntivo alla natura fisica dei luoghi, alla prospettiva dei costruttori e dei progettisti. Credo sia importante offrire al lettore vari percorsi di avvicinamento a un’architettura, al suo senso, senza illuderlo che ce ne sia una ottimale: illusoria e scintillante, oppure asettica e oggettiva. Ecco perché, come direttore di Abitare, ho voluto introdurre una dimensione letteraria negli articoli, nei servizi. Abbiamo chiesto a un gruppo di scrittori di localizzare il loro immaginario nelle architetture e negli spazi ospitati dalla rivista e di produrre dei racconti. Il racconto è un ottimo strumento per connettere la natura simbolica e quella fisica di uno spazio, per guidare il lettore in un viaggio tra i due mondi. Attraverso il racconto, il lettore diventa consapevole del suo ruolo di consumatore di immagini, miti, icone e narrazioni, e può sottrarsi ai cliché veicolati dai media globali. Ma ci sono anche altri modi di riflettere sulla geografia simbolica e materiale di un luogo. Grazie al contributo di Salottobuono, abbiamo provato a scomporre l’architettura facendone emergere la logica interna, la struttura. E ancora: abbiamo chiesto a fotografi di interpretare a loro modo uno spazio, guidando e arricchendo l’esperienza del lettore. Altre volte, invece, sono stati gli occhi degli abitanti a guidare il lettore: come nel caso dell’esperienza fatta con Ila Bêka e Louise Lemoine sulle architetture celebri esaminate dal punto di vista di chi le vive. Sono molte le possibilità che ha una rivista di lavorare sul piano simbolico, senza perdere di vista il referente fisico e minerale dell’architettura. Noi non ci limitiamo a rappresentare uno spazio, ma proponiamo al lettore, giocando assieme a lui, dei luoghi immaginari che rispettino un principio di coerenza (non di fedeltà) con l’architettura materiale, che giace, permane, da qualche parte del mondo esterno.

Passiamo dall’esperienza editoriale a quella espositiva. Lei ha realizzato varie mostre dei suoi progetti: potremmo dire che l’attività espositiva rappresenta lo strumento di un nuovo metodo di lavoro, più ibrido, capace di individuare soluzioni innovative attraverso una visione laterale del progetto?

Direi di no. L’esposizione di un progetto o di una ricerca ha piuttosto un significato etico. Mettere in mostra, assieme ai risultati, anche le premesse del tuo lavoro, dalla fase teorica al processo di realizzazione, consente al visitatore di verificare i presupposti originari del tuo progetto e di confrontarli con il risultato finale. Un’esposizione sottopone le tue idee a un processo di validazione/falsificazione. Rende fondate le eventuali critiche e ti aiuta a migliorare.

È l’approccio di Multiplicity, la sua agenzia di ricerca.

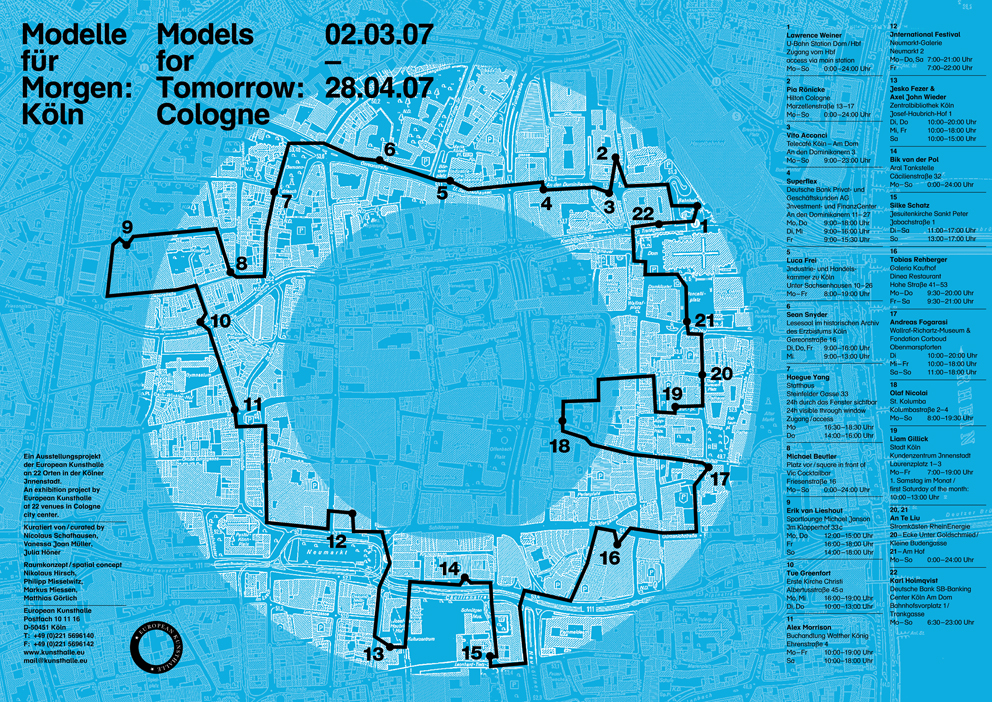

Nelle esposizioni delle ricerche di Multiplicity – a Kassel, alla Biennale di Venezia, al Musée d’Art Moderne di Parigi – abbiamo sempre cercato di raccontare non solo il risultato finale, ma anche i presupposti e la metodologia del nostro lavoro. È stato usato lo stesso approccio anche all’ultima Biennale di Architettura, quando, con Abitare, si è affrontata la questione della sostenibilità. Volevamo evidenziare gli effetti collaterali e imprevisti dovuti all’esacerbazione di alcune retoriche “ottuse” della sostenibilità, utilizzando il concetto di distopia, ovvero la rappresentazione di un mondo che si colloca in un futuro anti-utopico, indesiderabile. Nell’esposizione sulle “sostenibili distopie” abbiamo raccontato le premesse, i materiali selezionati e i passaggi logici che ci hanno portato a utilizzare il concetto di distopia.

Giocando con le parole, possiamo immaginare l’estetica come rappresentazione formale dell’etica?

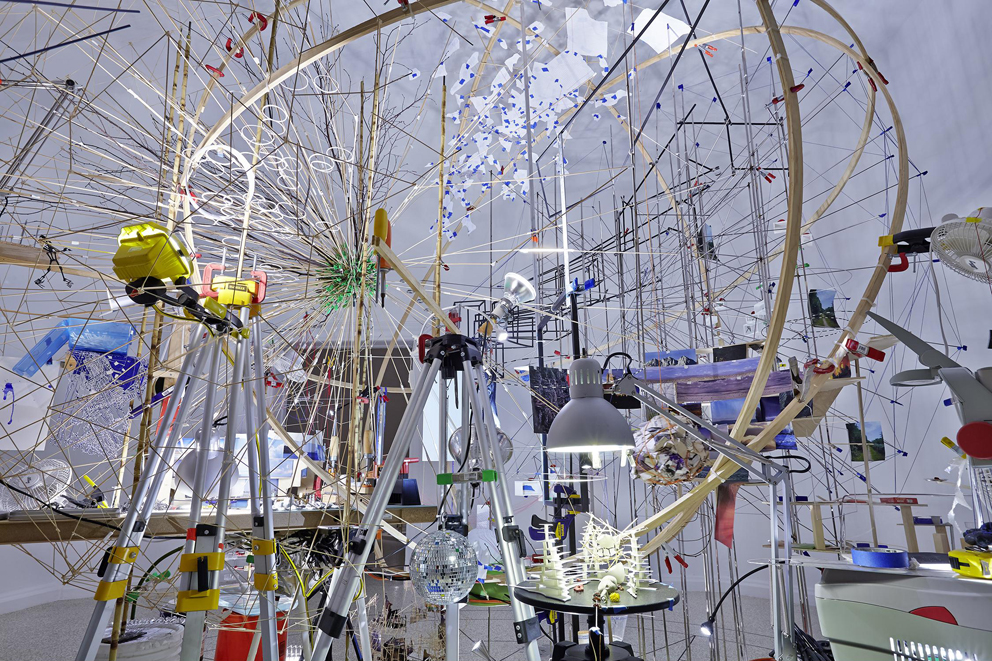

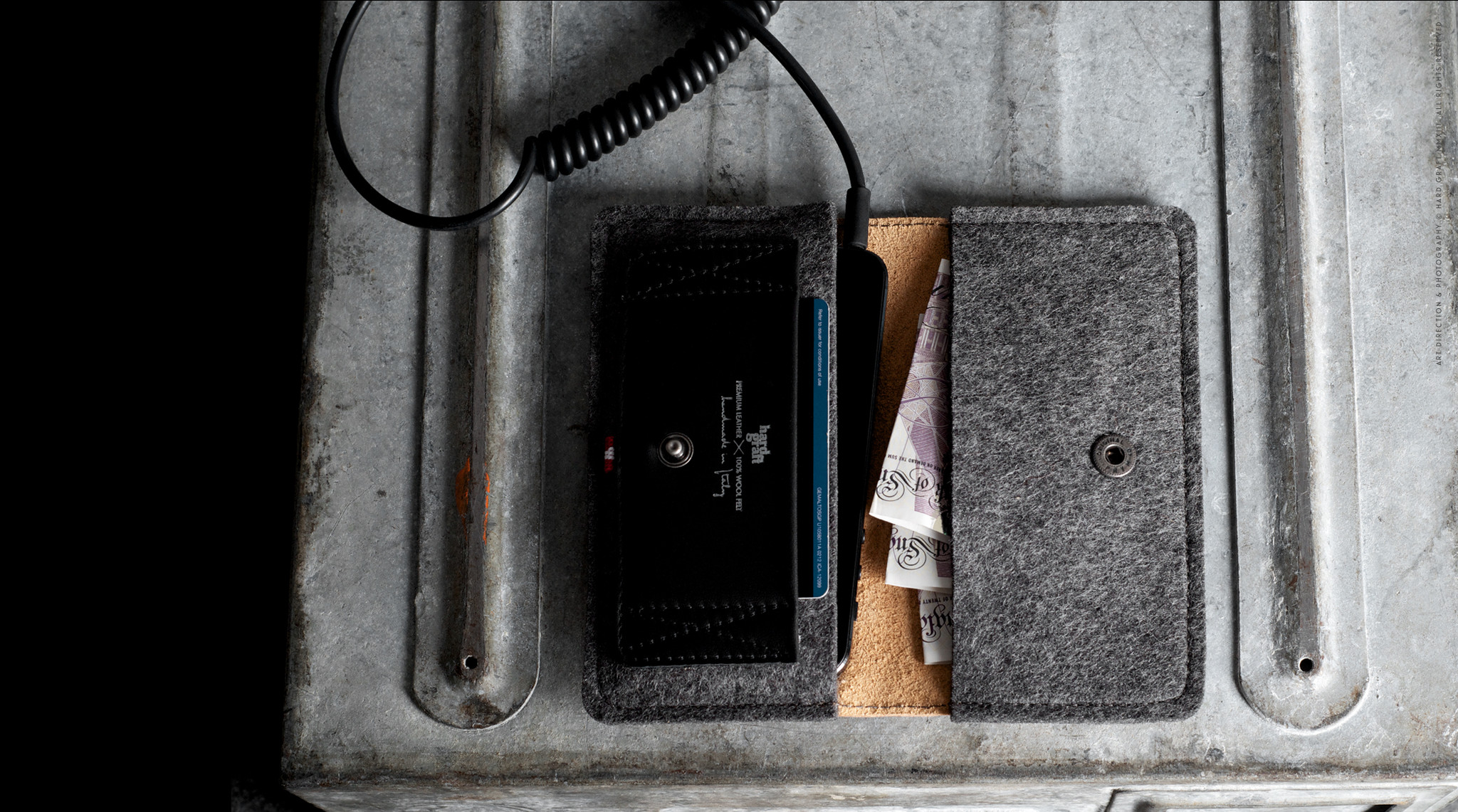

Non credo sia così. Ci sono delle valenze etiche fortissime nel fare architettura, che non stanno prima o dopo la dimensione estetica. Semplicemente, fanno parte delle scelte progettuali. Faccio un esempio per essere più chiaro: quando mi hanno dato l’incarico di realizzare una parte del progetto per il G8 all’Isola della Maddalena, nell’area dell’ex Arsenale della Marina Militare, ho dovuto affrontare da subito il problema di immaginare un insediamento con una duplice funzione: quella di un grande polo nautico che, inizialmente, per non più di tre giorni, avrebbe dovuto ospitare un evento planetario. L’insediamento è stato così pensato e progettato non solo come teatro di un evento eccezionale, ma anche come architettura permanente, destinata a valorizzare un contesto socio-economico penalizzato dalla dismissione di un’antica economia militare. Per questo, in totale sintonia con Renato Soru e Guido Bertolaso, abbiamo in un certo senso sfruttato il G8 come acceleratore di un processo virtuoso, che avrebbe regalato a un arcipelago in grande crisi la transizione da un’economia militare a un’economia basata sul turismo nautico e sportivo.

Che soluzioni architettoniche ha individuato per soddisfare la duplice funzione?

Ho scelto la sintesi formale: un grande tetto, un scatola sull’acqua, un insieme di stecche.

Quasi degli archetipi…

Il paesaggio dell’arcipelago è già molto ricco di figure, linee, volumi. Le strutture granitiche e basaltiche, scolpite nei secoli dai venti e dal mare, esauriscono, o quasi, ogni altra espressione formale. Il mio obiettivo era quello di costruire un’architettura essenziale che, reagendo con questo paesaggio esuberante, ne selezionasse delle prospettive, dei tagli.

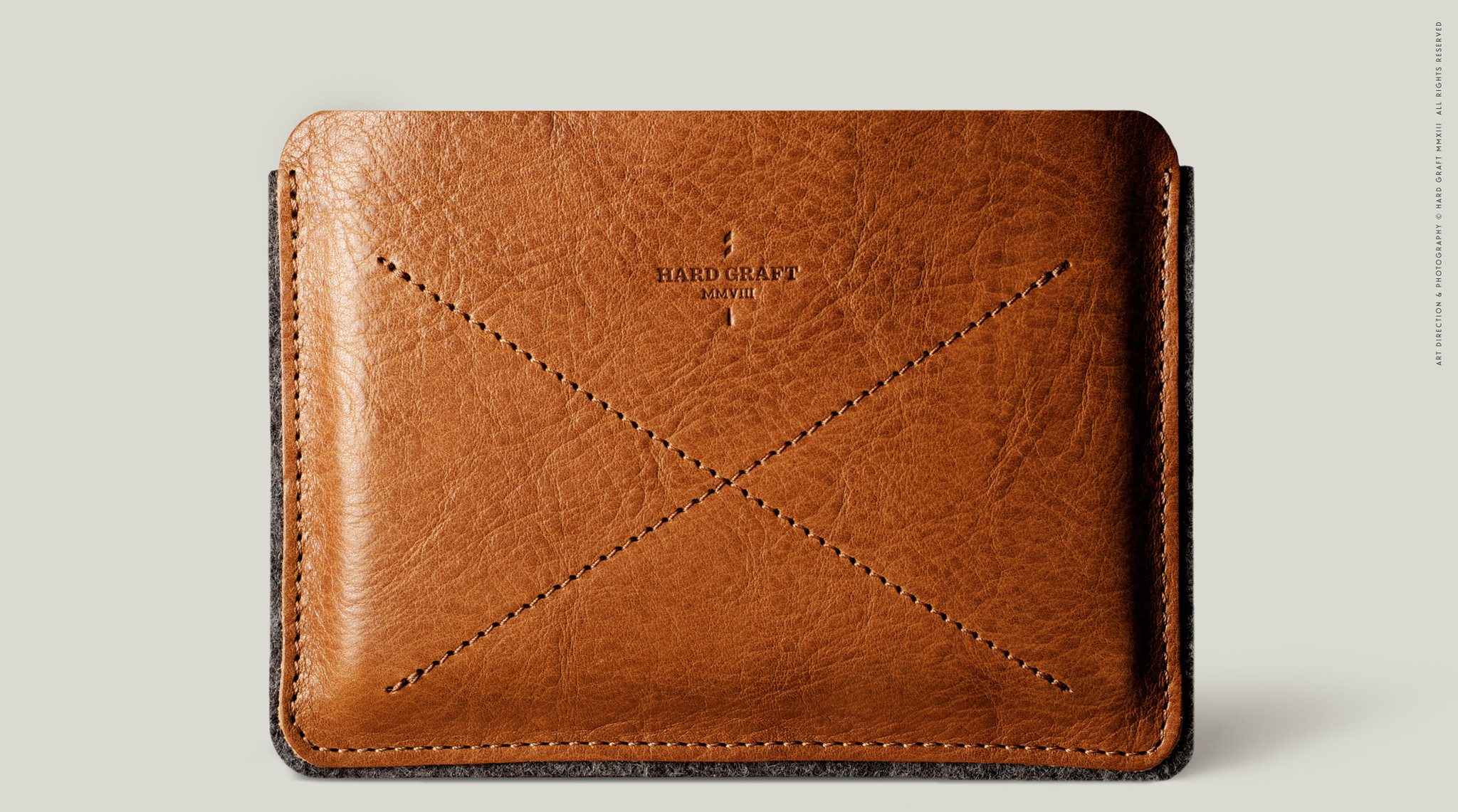

![Sede della rivista Abitare. Milano]()

Sede della rivista Abitare. Milano / Head offices of the magazine Abitare. Milan.

Tutto in funzione post summit…

Ogni edificio è stato realizzato con una sua funzionalità pro e post G8: abbiamo costruito un grande albergo che per tre giorni avrebbe ospitato la delegazione USA, un’area cantieristica che sarebbe stata usata come centro stampa, un grande polo nautico-commerciale che durante il G8 avrebbe ospitato i tremila delegati, uno yacht club dove si sarebbe dovuto svolgere il summit…

Che effetto ha avuto sui lavori in corso il cambio di location del G8, dalla Maddalena all’Aquila?

Un effetto relativo, per fortuna. Il cantiere è finito nei tempi previsti, con l’unica eccezione degli spazi verdi e alberati, che non erano stati finanziati. Nel complesso, si tratta di un’opera formidabile, se consideriamo la dimensione dell’insediamento e i tempi di realizzazione nel contesto italiano: tra progetto preliminare e costruzione sono passati appena 16 mesi, 10 dei quali di cantiere vero e proprio, comprese le bonifiche. E oggi, con il probabile arrivo della Louis Vuitton Cup, la propensione originaria del sito verso la vela e la nautica sportiva sarebbe ulteriormente confermata.

Passiamo all’ambiente, alla sostenibilità e al manifesto che ha scritto assieme all’economista Jeremy Rifkin.

Oggi convivono tre grandi retoriche sul tema della sostenibilità, tutte mirate a proporre una sorta di riconciliazione tra natura e città. Una prima retorica, di tipo tecnocratico, ci invita a credere che, potenziando e diffondendo ovunque i dispositivi di captazione e accumulo delle energie rinnovabili, sia possibile raggiungere una sorta di compensazione tra natura e sfera antropica: come se la gigantesca orma dell’uomo sulla natura potesse farsi più lieve, grazie a un formidabile sforzo tecnologico che riduce al minimo i consumi energetici. Una seconda retorica, invece, propone una riconciliazione fondata sull’idea di estensione delle pratiche di coltivazione: come se l’agricoltura, cioè il prendersi cura del terreno a fini produttivi, potesse diventare una grande panacea dei mali dell’urbanizzazione. Da qui, l’ipotesi di un allargamento delle aree coltivabili sia all’esterno sia all’interno delle nostre città. La terza retorica, infine, riconosce alla natura un grado assoluto di autonomia rispetto alla sfera antropica e cerca una riconciliazione basata su un principio di coesistenza: la città deve saper circoscrivere il proprio terreno e rispettare zone di naturalità pura, dove molteplici specie vegetali e animali possano crescere e svilupparsi in totale autonomia, fuori dal controllo umano.

Che rapporto sussiste tra queste retoriche e l’architettura?

Le tre retoriche hanno avuto un grande peso nell’architettura. Quella tecnocratica è stata rilanciata qualche anno fa da un libro scritto da un architetto, William McDonough, e da un biochimico, Michael Braungart, dal titolo Cradle to Cradle. Un libro che negli USA ha avuto un grande successo, nel quale si propone di estendere all’edilizia e all’urbanistica il principio della metabolizzazione (e del riciclo) di tutti gli artefatti umani, ispirandosi all’idea che le architetture possano funzionare come piante, come alberi, e dunque siano in grado di assorbire l’energia dal sole, dalla terra e di consumarla senza produrre residui. La seconda retorica, quella agro-produttiva, ha radici anche nel pensiero dell’architettura radicale, e in particolare nell’opera di Andrea Branzi: nel suo lavoro è sempre stata presente una riflessione sulla compatibilità tra artificio urbano e dimensione vegetale: da No-Stop-City (1969) al progetto teorico di Agronica (1995). Questa retorica promuove la valorizzazione dell’agricoltura di prossimità e lo sfruttamento di ogni superficie urbana disponibile a verde progettato. La natura viene coltivata in forma di giardino, di muro verticale, di bosco, di terreno agricolo, nella prospettiva di demineralizzare lo spazio urbano, trasformandolo in una superficie vegetale, verticale e orizzontale, continua.

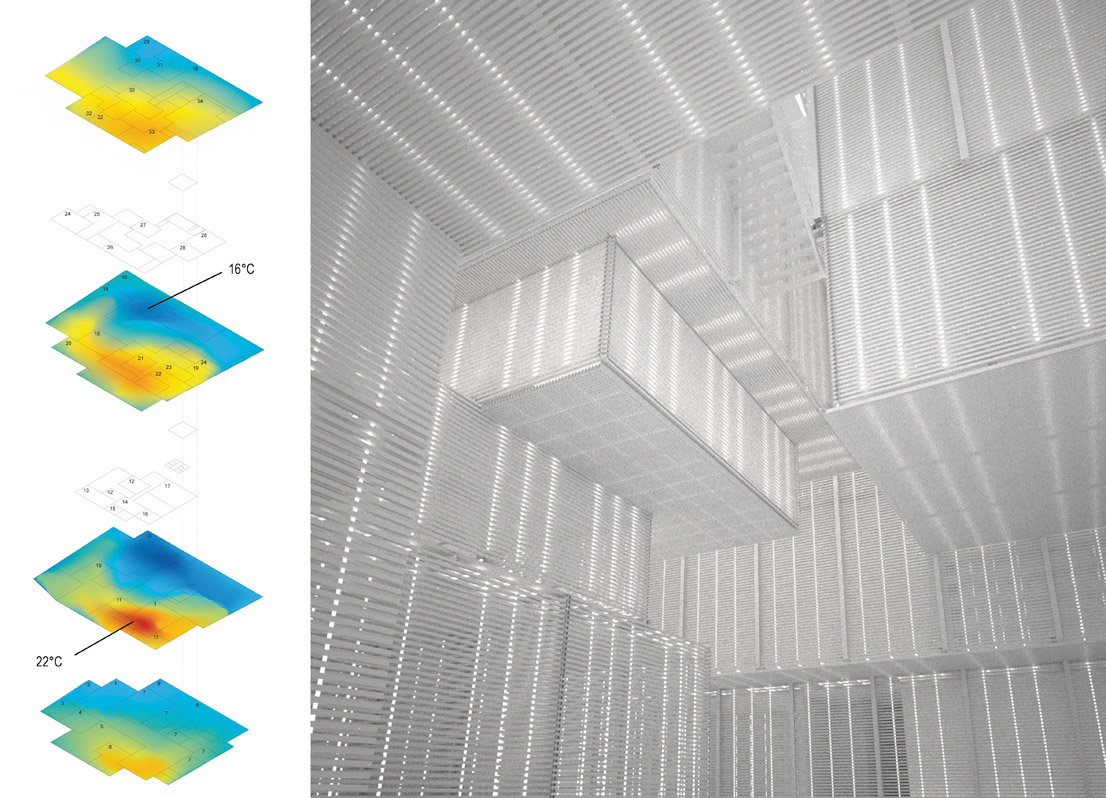

![Stefano Boeri, Sala Conferenze - Ex Arsenale Militare, Isola di La Maddalena, 2009]()

Stefano Boeri, Sala Conferenze – Ex Arsenale Militare, Isola di La Maddalena, 2009 / Stefano Boeri, The Conference Hall – Ex Military Arsenal, Island of La Maddalena, Sardinia, Italy, 2009

Poi c’è la terza retorica…

… che è quella più estrema, più spigolosa, ma anche la più interessante. Nega l’artificio e riconosce alla natura un’autonomia assoluta, tale da non poter essere copiata, coltivata o riprodotta. La natura è intesa come una sfera animale e vegetale indipendente, su cui non si può intervenire. Da qui l’idea di Terzo Paesaggio sviluppata dal paesaggista Gilles Clément, che legge in quel vasto insieme di spazi urbani abbandonati dall’uomo e riassorbiti dalla natura (binari, infrastrutture, aree industriali, capannoni ricoperti da rovi, sterpaglie, verde selvatico e residuale, erbacce) i germi di una nuova spazialità, imprevedibile e non condizionabile dalla progettazione urbana. La cosa che mi interessa di più di quest’ultima retorica è che pone finalmente, in modo estremo, la questione di un’etica urbana non antropocentrica, di una disciplina che arrivi a considerare, anche dentro il territorio urbanizzato, zone di totale autonomia della natura.

E Rifkin?

Il manifesto pubblicato su Abitare, l’anno scorso a ottobre, firmato a Venezia con Rifkin e altri architetti internazionali, riprende soprattutto la prima retorica e la fonda su una suggestiva ipotesi di democratizzazione dell’innovazione tecnologica: ogni edificio deve funzionare come una centrale energetica. Il manifesto ha il grande pregio di rendere socialmente ed economicamente auspicabile, oltre che realistica, una politica urbana della sostenibilità. Una visione ecologica della città che richiede una responsabilità dell’individuo e che mira a coinvolgere puntualmente i progettisti per costruire reti locali intelligenti, introducendo così una dimensione politica nell’architettura.

Prima si parlava di distopia: non trova che queste tre teorie possano dar luogo a visioni estremizzanti?

Sì. Queste tre retoriche producono delle potenziali distopie, degli incubi. Da un lato, c’è il rischio che si torni a una visione fortemente tecnocratica del paesaggio urbano. Penso per esempio, al progetto di Norman Foster per una città totalmente sostenibile nei pressi di Abu Dhabi, dove si costruisce una macchina costosissima e potente per dimostrare che lo spazio urbano può non danneggiare la natura, senza considerare che costruendo una nuova città si sottrae comunque spazio a una naturalità originaria. Un vero paradosso. Ma penso anche alle migliaia di dispositivi energetici che rischiano di invadere lo spazio delle nostre città, anche quello verde. Una seconda distopia può nascere dal fatto che una natura coltivata e progettata lascia ben poco spazio all’imprevedibilità: avremo forse più verde urbano, pulito e ben coltivato, ma rischiamo di avere meno spazio dedicato alla libera e ingovernabile articolazione dei comportamenti umani. Del resto, anche la visione di una naturalità non governata che si riprende alcuni spazi cittadini, se non viene affrontata con attenzione può portare a paradossi e problemi, come quelli causati dalla crescente presenza di specie animali non domestiche (cinghiali, cervi, volpi, ecc.) nelle aree urbane delle città europee.

E dal punto di vista della progettazione?

Le visioni di William McDonough e di Rifkin sono interessanti da un punto di vista politico, perché introducono una forma di sostenibilità dal basso: tutti noi dovremmo preoccuparci che un edificio funzioni come una centrale, che un quartiere operi come una rete locale di produzione, consumo e distribuzione dell’energia. La visione di Branzi, quella della vegetalizzazione della città, è invece la più potente sul piano della progettazione architettonica, richiama una lunga storia di progetti e ricerche che vanno dalle costruzioni verdi di Emilio Ambasz fino al nostro progetto milanese di Bosco Verticale. La retorica del Terzo Paesaggio consente invece di ragionare su frammenti di paesaggio naturale spontanei e inattesi, per certi versi incontaminati, su cui esercitare consapevolmente una rinuncia creativa.

Cambiamo argomento: come cambia l’abitare? È sempre più diffusa, mi pare, una forma dislocata e policentrica di abitare, quasi un abitare in valigia…

È vero, ma questa idea di abitare temporaneo, nomade, convive con una fortissima esigenza di radicamento, di ritorno a un rapporto con i luoghi, con la famiglia intesa come comunità parentale allargata. Con Multiplicity e Abitare abbiamo condotto alcune ricerche sul cambiamento delle tipologie abitative che confermano questa tendenza. C’è oggi un grande bisogno di radicamento all’interno di spazi, dove però si accetta sempre di più la coabitazione con individui che non appartengono solo al nucleo familiare ristretto. Questa propensione alla coabitazione è dovuta a diversi fattori: l’evoluzione dei bisogni di spazio delle famiglie e delle aspettative di vita dei suoi membri, lo sviluppo di progetti di lavoro temporanei e di abitudini nomadi, e la necessità di risparmiare, di condividere e ridurre le spese di alloggio. Coabitazione significa che la casa tende sempre più a diventare uno spazio a geometria variabile, in grado di adattarsi a bisogni mutevoli, ma significa anche convivialità, socializzazione, maggior attenzione alla cultura del cibo. La cucina, e non più il salotto televisivo, è tornata infatti a essere il luogo centrale di interazione tra individui che convivono. Una situazione ben descritta, con anticipo, da Ferzan Ozpetek ne Le fate ignoranti.

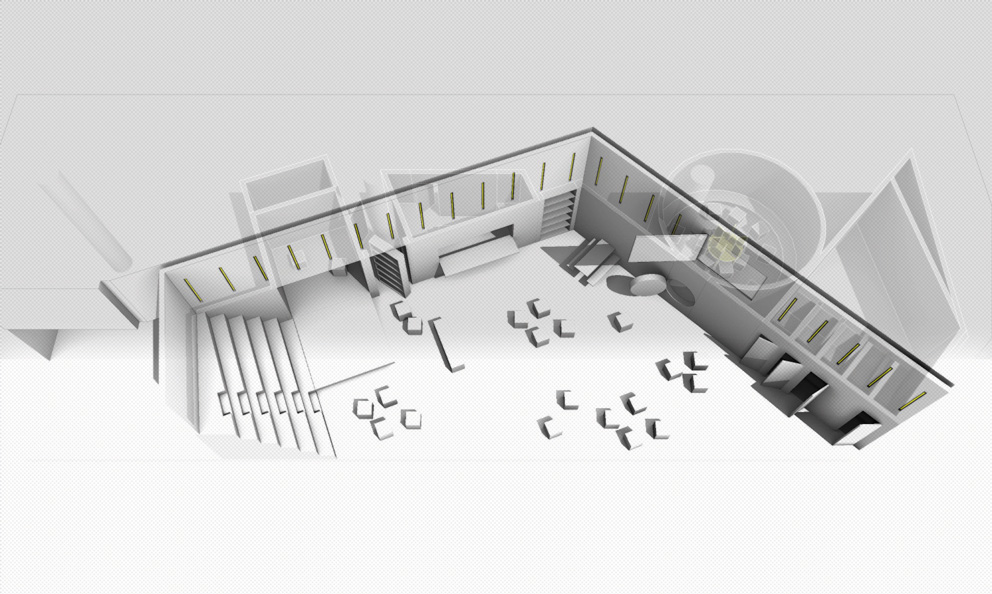

![Boeri Studio, Centre Régional de la Méditerranée, Marsiglia, 2009. Centro polifunzionale]()

Boeri Studio, Centre Régional de la Méditerranée, Marsiglia, 2009. Centro polifunzionale / Boeri Studio, Centre Régional de la Méditerranée, Marseilles, 2009. Multifunctional Centre

Ci sono progetti in corso o passati ai quali è più legato?

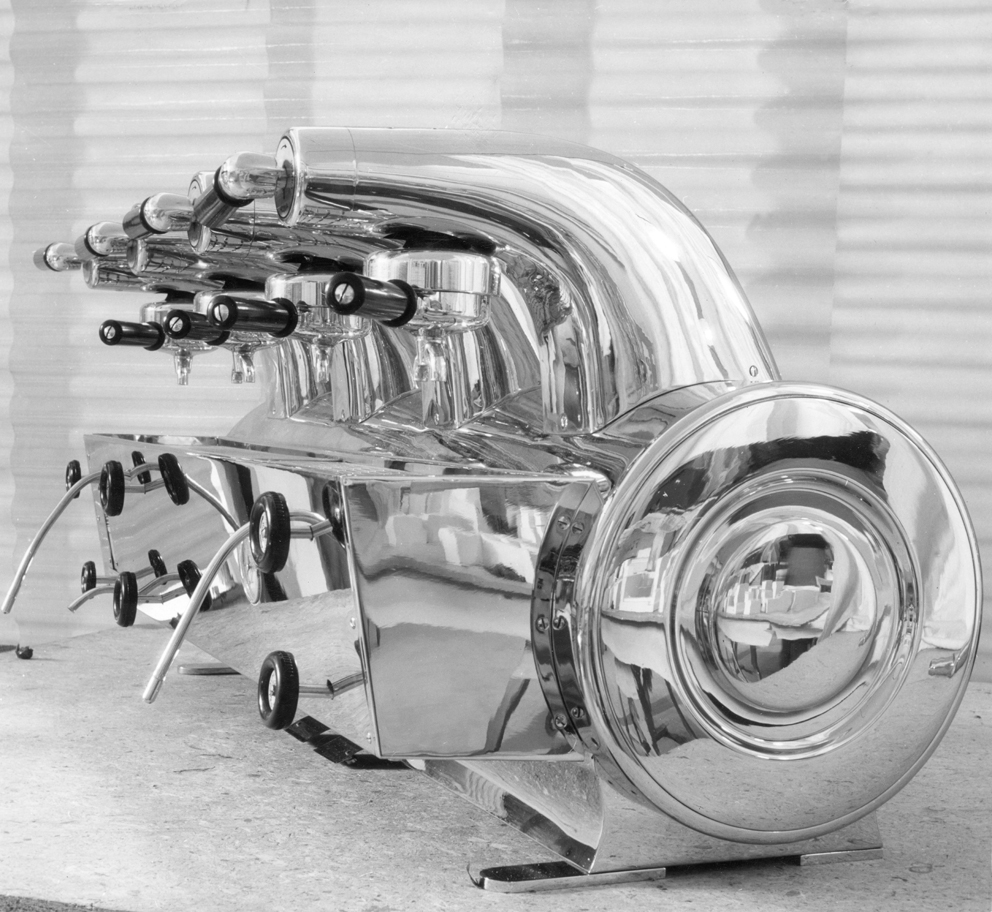

Certamente. Il primo che mi viene in mente, quello a cui sono più affezionato, è la centrale geotermica Enel, Bagnore 3, realizzata nel 1997 nei pressi del monte Amiata, a Santa Fiora di Grosseto. La committenza ci aveva chiesto di nascondere l’impianto all’interno di scatoloni industriali, cercando di camuffare la centrale. Noi, invece, abbiamo scelto di dare massima visibilità all’impianto, trasformando una serie di ingranaggi anonimi e impresentabili (i macchinari e le torri di raffreddamento) in una grande macchina unitaria che non ha paura di dialogare con il paesaggio. Poi ci sono i progetti legati al mare, forse tra i miei lavori più importanti. Uno è quello di Marsiglia, nato nel 2004 e giunto solo ora alla fase cantieristica, dopo una storia lunga e controversa. Si tratta di una architettura-darsena destinata ad attività di ricerca e documentazione sul Mediterraneo. Un grande edificio a C che ospita al suo interno il mare e lo copre con un tetto abitato (uno spazio espositivo) che ha uno sbalzo di 40 metri. Il centro sorgerà nell’area geografica in cui si forma il Maestrale, che poi soffia fino alle Bocche di Bonifacio, dove è nata in questi mesi l’architettura del centro congressi alla Maddalena. Nell’edificio di Marsiglia, l’acqua penetra tra i due piani orizzontali e crea una grande piazza di mare, in grado di accogliere barche a vela e piccole imbarcazioni da diporto. Alla Maddalena, la grande sala destinata a ospitare il summit, protesa sull’acqua, consente una vista grandangolare di tutte le isole dell’arcipelago. Mi piace l’idea che queste due architetture saranno percorse dallo stesso moto ventoso.

Lontano dalle città e dalle grandi periferie urbane…

In realtà, sono molto legato anche all’edificio di residenze popolari che, con Gianandrea Barreca e Giovanni La Varra, abbiamo realizzato a Seregno, nella periferia di Milano, dove si è cercato di lavorare sulla geometria variabile dell’abitare e sul tema della coabitazione: prevedendo spazi mutevoli per famiglie che possono aumentare e diminuire di dimensione, realizzabili a costi molto contenuti. In fondo, l’opposto di quanto abbiamo progettato nel quartiere Isola, a Milano, con il Bosco Verticale. Un intervento inconsueto, per certi versi altamente sperimentale, destinato a un’utenza facoltosa. Un progetto in bilico tra la retorica tecnocratica e quella branziana di cui si parlava prima, nel quale abbiamo messo in secondo piano l’architettura, privilegiando il piano strutturale e ingegneristico di una infrastruttura capace di sostenere e nutrire alberi fino a cento metri d’altezza… Alberi che, all’ultimo piano, arrivano a dodici metri! Una vera sfida, che mi ha divertito molto.

Bisogna pur divertirsi…

Mi incuriosiva questa scelta consapevole di rinunciare all’architettura come semplice forma espressiva, lavorando più sull’aspetto quasi meccanico di soluzione di un problema concettuale: come portare un abete a quella altezza? Come sostenere dei balconi appesantiti dalla terra necessaria alla vita degli alberi? Come costruire un bosco verticale composto da più di 1200 alberi nel centro di Milano? Il committente, Manfredi Catella, amministratore delegato di Hines Italia, inizialmente aveva ragionevoli dubbi sulla nostra proposta, ma alla fine ha accettato di condividere con noi il rischio di un’architettura mai realizzata. Così, grazie a una specie di radicalità cosciente e alla certezza della sua fattibilità, il Bosco Verticale sta andando in porto.

KLAT guarda anche all’arte contemporanea: cosa ne pensa della relazione fra arte e architettura?

È una relazione feconda, che ho praticato a lungo, anche in modo bulimico e strumentale. Ho sempre considerato l’arte come alimento per l’architettura. Quando nel 2002, con Multiplicity, siamo stati invitati a Kassel per Documenta 11, eravamo gli unici italiani presenti. Quella partecipazione ha generato invidie, ambiguità, equivoci, come se avessimo voluto invadere un campo a noi estraneo. In realtà, io non ho mai pensato di fare l’artista. L’arte è stata spesso un committente per noi, ci ha dato grandi opportunità di fare ricerca e una totale libertà di pensiero. Ma oggi sono pochi gli artisti che trovo interessanti. Se penso alle esperienze stimolanti prodotte ultimamente in campo artistico, mi vengono in mente poche cose e pochi nomi. Tra i nomi, c’è sicuramente quello di Hans Ulrich Obrist, carissimo amico che crede di essere un curatore e invece è un grande artista contemporaneo. Da anni, Obrist si muove nel mondo accumulando e collezionando, in modo quasi parossistico e accelerato, interviste, contatti, conversazioni con i protagonisti della cultura globale, per costituire una sorta di archivio planetario del pensiero. Un’utopia concreta, una follia necessaria, straordinaria, praticata grazie a un’opera individuale, la sua vita, che è quasi una Body Art di nuova generazione. Hans sfrutta il format dell’intervista per generare relazioni, che a loro volta producono idee. Il resto del panorama artistico mi pare un po’ noioso, perché costretto spesso all’affannosa ricerca della provocazione. Per non parlare del connubio arte e moda o arte e design, una sorta di abbraccio mortale e suicida che sta alimentando, in giro per il mondo, una patetica fiera mobile delle vanità.

/

In response to great demand, we have decided to publish on our site the long and extraordinary interviews that appeared in the print magazine from 2009 to 2011. Forty gripping conversations with the protagonists of contemporary art, design and architecture. Once a week, an appointment not to be missed. A real treat. Today it’s Stefano Boeri’s turn.

Paolo Priolo

Interview by Pietro Los. Klat #01, winter 2009-2010.

An important player on the international architectural scene, a critical and innovative designer, founder of the research group Multiplicity and editor of Abitare magazine, Stefano Boeri has just finished re-designing the ex-military zone of La Maddalena, in Sardinia, and has re-started work on an important architectural-shipyard in Marseilles. In the meantime, he is finishing off his Vertical Forest in Milan, a powerful example of experimental residential architecture. KLAT caught up with him to discuss theory and practice and the links between theory and planning.

![Stefano Boeri, Sala Conferenze - Ex Arsenale Militare, Isola di La Maddalena, 2009]()

Stefano Boeri, Sala Conferenze – Ex Arsenale Militare, Isola di La Maddalena, 2009 / Stefano Boeri, The Conference Hall – Ex Military Arsenal, Island of La Maddalena, Sardinia, Italy, 2009

How has the architectural profession changed in recent years and is it still changing?

It hasn’t changed all that much, if the truth be told. Our profession works at two levels: one which tends to include the outside world and one which excludes that world. Let me explain. The inclusive level, the analytical level, is that which moves towards a kind of overdose of information. Being an architect means collecting ideas, information and opinions about the context in which we work, about users and materials, all the time. This is a way of including the outside world in our work, which helps us to imagine the future of a place, to fill it with ideas and imagine changing scenarios. Beyond this dimension, there is another, which is very different, and is exclusive, based as it is around the increasing possibility of selection. This level pushes us towards solutions, towards finalised projects, something which is finished and individualised, the complete and unique form through which we decide to change a part of the city, a building, a design object. When we plan, we need to bring together analytical knowledge, which opens out to the world, with a kind of knowledge which excludes the outside world, apart from that tiny part which regards our work as planners. The relationship between these two levels, between analysis and planning, is complex and often conflictual. But it is at the heart of the architectural profession. The specific nature of every architect is intimately linked to this relationship.

How do you deal with this issue yourself?

I think that this relationship becomes interesting, for me, when you can keep the two levels apart, and try to avoid one dominating the other, or that one develops first, or without, the other. Both levels need to be experienced autonomously and simultaneously, and the conflict between them, and the way they clash, needs to be free to create unlikely associations, unlikely meanings, new ideas. I have never believed in the logical or temporal primacy of analysis over planning or vice versa. I believe, instead, that we need to learn to manage the inevitable conflict between these two dimensions of an architect’s work. The most interesting architects are those who work in a schizophrenic way.

You edited Domus from 2004 to 2007 and since then you have been editor of Abitare. What role does a specialist architecture magazine play in today’s world and what role should it play?

Every architectural magazine defines its identity through the relationship it creates between buildings made of stone and those made with paper. That is, in the way in which it looks to close the gap between the sensory experience of architecture which exists in the material world, in the outside world, and the intellectual experience linked to architecture, which is seen in the imaginary images we create as readers. A magazine like Abitare describes architectural objects which the reader will probably never see, live in or touch – but can only understand through the aesthetic and symbolic imaginary produced by the magazine. The relationship between the physical and symbolic nature of a place is a very delicate one. Recent architectural identity has developed more and more of a dualistic nature. Large scale architecture, today, has a double and parallel set of existences. There are the famous buildings, represented by the global media, who maintain their physical and material identity in some part of the world. On the other hand, their symbolic and immaterial nature is so powerful that they have become semblances of reality, autonomous with regard to their original form. Sometimes, these two ways of existing are not even linked by cause and effect. Some forms of architecture continue to exists as cult images in the imaginary world, even when their life as material buildings has lost its charm and attractiveness.

Where does Abitare fit into these two worlds?

We have tried to help the reader to reduce the distance which separates the imaginary forms from the material buildings themselves, by using a mix of rigour and creativity. Alongside the rigid, clear description of architecture in a more traditional way (through maps, photography, plans), we have utilised interpretations infused with fantasy and arbitrary descriptions of places and spaces. I don’t believe that descriptive faith can be the main element for an architectural magazine, or that there is a unique relationship between material reality and representation. I think we need to see things from different points of view: pure interpretations of reality, parallel worlds which can add something to the physical nature of places, as well as to the opinions of builders and planners. Readers need to be given alternative ways of understanding architecture, without the illusion that only one way is the best. Thus, as editor of Abitare, I have tried to introduce a literary dimension to articles and reports. We have called on a group of writers to use their imagination in architectural terms, and to produce stories for the magazine. Stories are an excellent way to connect the symbolic and physical nature of space, and to guide the reader in a journey between these two worlds. Through stories, the reader becomes aware of his or her role as a consumer of images, myths, icons and stories, and can escape from the clichés found in the global media. But there are also other ways to think about the symbolic geography of places. Thanks to the work of Salottobuono, we have tried to deconstruct architecture and help its internal logic and its structure emerge. Moreover, we have asked photographers to interpret spaces in their own way, guiding and enriching the reader’s experience. On other occasions, the eyes of the inhabitants have been a guide for the reader, as in the pieces with Ila Bêka and Louise Lemoine which looked at celebrated architectural buildings from the point of view of those who live within them. A magazine has a lot of scope in terms of working on the symbolic level, without forgetting the physical and actual aspects of architecture. We do not just represent space, we propose it to the reader. We play games with our readers, inventing imaginary places which are coherent with (but not faithful to) material forms of architecture which exist somewhere in the outside world.

Let’s move onto your work with exhibitions. You have created a number of exhibitions linked to your projects. Would it be correct to say that for you exhibitions are used as a new kind of way of working, something which is more hybrid, and able to detect and create innovative solutions through a more oblique way of seeing a project?

I don’t think so. Exhibiting a project or the results of research has an ethical implication. When you put the theoretical areas of a project on show, alongside what was actually constructed or the research which was carried out, this allows visitors to check on the original presuppositions of your work and compare them with the final results. Exhibitions allow your work to be validated or seen as false or wrong. It shows you if the criticisms levelled at the work at the beginning were mistaken, and it helps you improve.

And how does Multiplicity, your research group, work?

When we have set up exhibitions using the work of Multiplicity – in Kassel, at the Venice Biennale, at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris – we have always tried to analyse not only the final results, but also the background and methods to our work. The same approach was adopted with Abitare, at the most recent Biennale of Architecture, which looked at the issue of sustainability. We wanted to show the collateral and side-effects which can arise from a rhetorical and stubborn approach to sustainability by using the concept of dystopia – that is the representation of a world as an anti-utopian future. In the exhibition dedicated to “sustainable dystopias” we looked at the background, the selection of material and the ways in which we were pushed to examine at the idea of dystopia.

![Stefano Boeri, USE - Uncertain States of Europe, Bordeaux, 2000. Installazione per la mostra Mutations. Multiplicity, Milano]()

Stefano Boeri, USE – Uncertain States of Europe, Bordeaux, 2000. Installazione per la mostra Mutations. Multiplicity, Milano / Stefano Boeri, USE – Uncertain States of Europe, Bordeaux, 2000. Installation for the exhibition Mutations. Multiplicity, Milan

Can we think of aesthetics as the formal representation of ethics?

Not really. Ethics is central to architectural practice, but it is neither more or less important than the aesthetic dimension. Put simply, these are choices made during work on a project. I want to give you an example of this. When I was given the job of creating part of the project for the G8 on the island of La Maddalena, in the ex-military shipyard there, I had to think of this building in two ways: as a permanent large-scale nautical area, which would also be required for a global event, only for three days. The building was conceived as something which would last beyond that initial, theatrical event, and have a use and a function that would compensate for the loss of the military economy, which has a long history in the area. In this way, through working with Renato Soru and Guido Bertolaso, we exploited the G8 to create a virtuous circle of events, which was to create a new form of economy – based on nautical and sporting tourism and not on the military – for an archipelago undergoing something of a crisis.

What kind of architectural solutions did you come up with to create this double use?

I chose a formal synthesis of styles: a large roof, a box on the water, a collection of pipes.

Almost as if they were archetypes…

The landscape in that archipelago is already rich in figures, lines, shapes. The granite and basalt structures, shaped by centuries of wind and sea, go beyond anything which man could ever invent. My aim was to construct a minimalist form of architecture which, in contrast with these exuberant landscapes, could express a series of views and non-views.

All for a post-summit environment…

Every building was created with this double use in mind – pro and post-G8. We built a large hotel which was to host the US delegation, a building site which was to be used as the press office, a large nautical and commercial area which would be home to the 3000 delegates during the G8 and a yacht club where the summit was to take place.

What effect did the change of location of the G8, from La Maddalena to Aquila, have on this work?

Only a relative effect, luckily. The building was finished on time, apart from the green and tree-lined spaces, which didn’t receive funding. Overall, it was an impressive achievement, given the limited time at our disposal and the normal time required in an Italian context for work of this kind. Only 16 months went by between the preliminary project and building being completed, and only 10 months of real building took place (including the clean-up beforehand). Today, with the probable arrival of the Louis Vuitton Cup, the original potential of the site as a place for sailing and water sports is being realised.

Let’s move onto the question of the environment and sustainability. You have issued a manifesto together with the economist Jeremy Rifkin.

Today there are three grand rhetorical narratives concerning sustainability, which exist in parallel, and all three are attempting to create a kind of reconciliation between nature and the city. The first (rhetorical) narrative, which has a technocratic edge, asks us to believe that by strengthening and creating systems of renewable energy, a kind of stand-off can be reached between nature and the human world – as if the enormous weight placed by man on nature can be eased through technology which reduces energy consumption to a minimum. A second rhetorical idea, however, argues for reconciliation based upon an increased in cultivation – as if agriculture, that is the use of land for productive ends, can resolve the problems created by urbanisation. So there are proposals to increase the land available for agricultural use, both within and outside of our cities. The third rhetorical idea, finally, argues for co-existence and recognises that nature has some autonomy with regard to the human sphere. Cities need to be limited in size and respect areas of pure nature, where various types of vegetation can grow and develop in total autonomy, outside of human control.

What is the relationship between these three forms of rhetorical argument and architecture?

All three have had a great influence on architecture. The technocratic argument was re-launched some years ago through a book called Cradle to Cradle, written by an architect, William McDonough, and a bio-chemist, Michael Braungart. In the United States this book had a huge impact. It argues that the principle of metabolisation and recycling of all human artefacts should be extended to building and planning, and that architecture can work in the same way as plants and trees do, and that we are therefore able to absorb energy from the sun, the land and to consume it without producing waste. The second rhetorical argument, which I call agro-productive, has roots in radical architectural theory, and in particular in the work of Andrea Branzi. Branzi has always been interested in questions linked to the compatibility between urban human spheres and the realm of vegetation, from No-Stop-City (1969) to the theoretical project known as Agronica (1995). This rhetorical argument argues for the development of neighbourhood agriculture and the exploitation of every possible urban space for planned green areas. Nature is cultivated as a garden, with its walls seen as a kind of wood, and agricultural land is increased in order to de-mineralise urban space, transforming it into a continuous zone of vegetation, which is both vertical and horizontal.

And the third rhetorical argument?

This is the most extreme approach of all, and the most difficult to deal with, but also the most interesting. It denies that the artificial world exists in some areas and argues that nature should be totally autonomous, and should not be copied, cultivated or reproduced. Nature is seen as an independent animal and vegetal sphere, which cannot be altered by man. Hence the idea of the Third Landscape developed by Gilles Clément, who sees those vast abandoned spaces which have been reappropriated by nature – rail tracks, infrastructure, industrial areas, buildings covered by wild green spaces – as the seeds of new forms of space, which are unpredictable and unconditioned by urban planning. What interests me most, in this type of approach, is that it looks in an extreme way at urban ethics without the human dimension, and is able to understand a zone dominated by autonomous natural forms, even within an urban area.

And what about Rifkin?

The manifesto which was signed at Venice with Rifkin and other international architects, published last year in Abitare, October issue, is linked above all to what I have referred to as the first rhetorical argument and to the possibility to democratise technological innovations: every building should work like a power station. The manifesto is important in that it calls for sustainable urban politics which is both socially and economically useful as well as realistic. This is an ecological vision for the city which demands that individuals be responsible and which tries to bring in the planners in order to build intelligent local networks, which introduces a political dimension into architecture.

Earlier you discussed dystopias. Don’t you think that these three theoretical forms can produce extreme visions?

Yes. These three rhetorical arguments are all potential dystopias or even possible nightmares. On the one hand, there is a risk of a return to technocratic approaches to urban landscapes. For example, there is Norman Foster project for a totally sustainable city close to Abu Dhabi, where expensive structures will be built in order to show that urban space does not damage nature, without taking into consideration the fact that the construction of a new city in itself takes away space from the natural world, or from what was originally there – a real contradiction. But I am also talking about the thousands of energy saving devices or energy collecting devices which take up much space, including green space, in our cities. A second dystopia could originate with the fact that cultivated and planned nature assigns little role to chance. We might have more green spaces in our cities, which are clean and well organised, but we risk having less space which is dedicated to free and ungovernable use. Moreover, even the idea of a non-governed nature, which takes control of some city spaces, if not thought about seriously can create further problems, such as those linked to the proliferation of non domestic animals – wild boar, deer, foxes, ecc. – in urban areas in European cities.

And what about planning?

The ideas of William McDonough and Rifkin are interesting from a political point of view, because they point towards sustainability driven from below. We should all be interested in the fact that a building works like a power plant and that neighbourhoods create local networks for producing, consuming and distributing energy. Branzi’s vision, that of a vegetalization of the city, is the most powerful we have from the point of view of architectural planning – and relates to a long history of projects and research which range from the green buildings of Emilio Ambasz right up to our Milanese vertical wood project. The rhetoric behind the Third Landscape helps us understand many spontaneous and unexpected fragments of the city, which are also to some extent uncontaminated, and could be left to flourish through a sort of creative refusal to act.

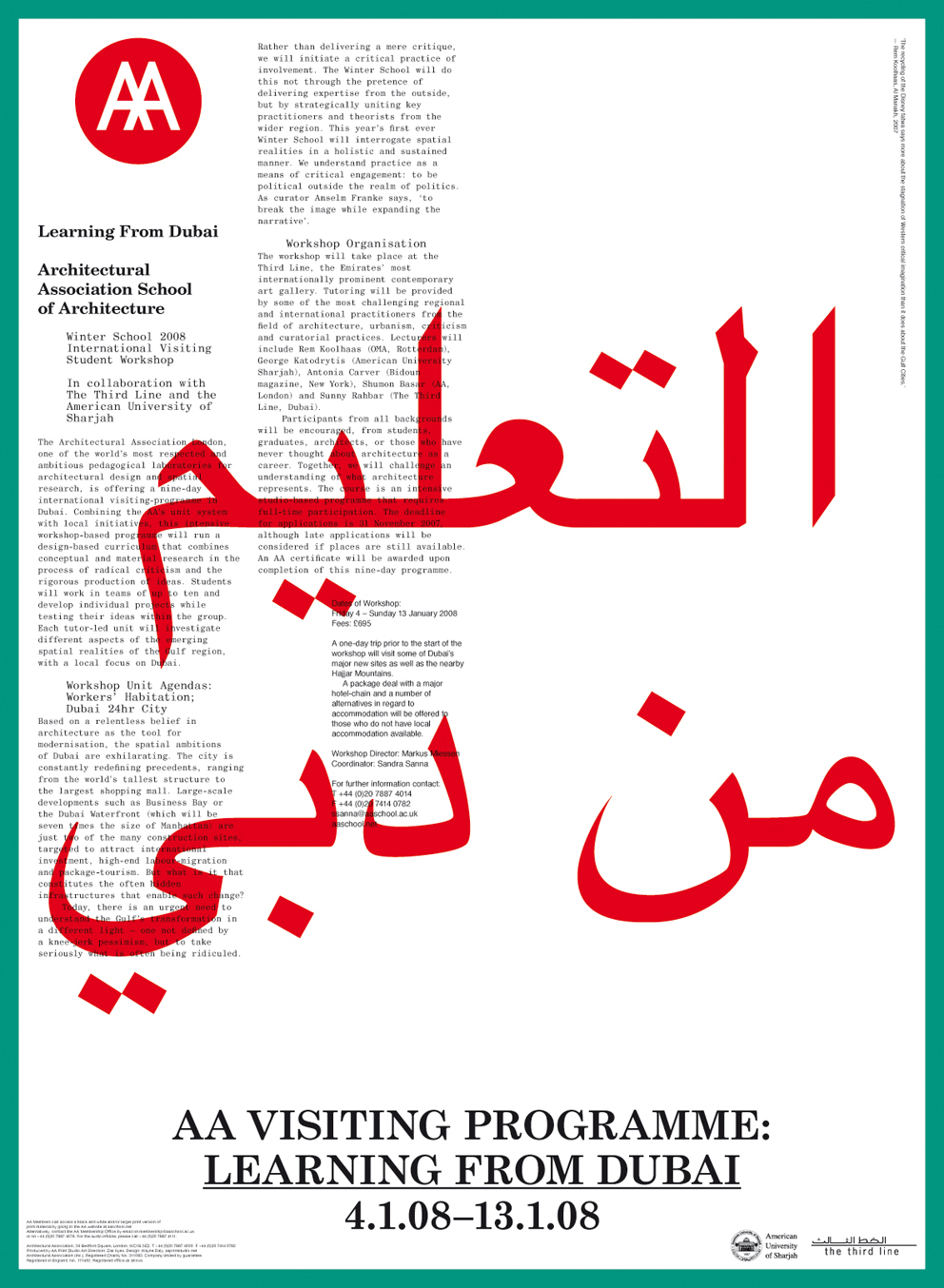

![Stefano Boeri, Enel Bagnore 3, Santa Fiora di Grosseto, 1997. Impianto geotermico]()

Stefano Boeri, Enel Bagnore 3, Santa Fiora di Grosseto, 1997. Impianto geotermico / Stefano Boeri, Enel Bagnore 3, Santa Fiora di Grosseto, Tuscany, Italy, 1997. Geothermal Plant

Let’s change the subject. How are ways of living changing today? It seems to me that spread out and polycentric forms of living are more and more common – people live in a kind of suitcase…

You are right. But this idea of temporary living, this nomadic urge, exists alongside a strong desire for roots, for a link to place, with families seen as extended parental communities. With Multiplicity and Abitare we have carried out some research into changes in forms of residence which confirm this tendency. Today many people want to put down roots within lived spaces, but they are also ready to accept co-habitation with individuals who are not part of the family unit. This tendency to co-habit is the result of different factors: changes to family spaces and life expectations within the family, the development of temporary work and nomadic movement, the need to save money, to share and reduce living costs. Co-habitation means that homes have become more and more flexible, more and more able to adapt to different needs, but it also implies socialisation, conviviality and closer attention to cooking and food in general. The kitchen, and not the living room with its TV, has become, once again, the key site of interaction between co-habiting individuals. This situation was depicted (ahead of its time) in Ferzan Ozpetek’s film, Le fate ignoranti.

Are there any ongoing or past projects of yours of which you are particularly fond?

Of course. The first which springs to mind, and one which I am most attached to, is the Enel geo-thermal Bagnore 3 plant, built in 1997 close to Monte Amiata, at Santa Fiora di Grosseto. We were asked to hide this building within some industrial boxes. But we decided to make the centre highly visible, transforming a series of anonymous and ugly objects (the machines and the cooling tower) into a big unitary object which was not afraid to build a relationship with the landscape. Then there are the projects linked to the sea, which might be seen as my most important work so far. One was in Marseilles, was started in 2004 and is only now at the building stage. It is an architectural-shipyard which is destined to be a centre for research and documentation on the Mediterranean region. It is a large C-shaped building which has the sea inside and is covered with a roof which is also used as an exhibition space. The centre is being built in an area where the Mistral wind forms, and then blows right up to the Bocche of Bonifacio, where the architecture linked to the conference centre of La Maddalena is being created. In the Marseilles building, water comes in through two horizontal floors and creates a large sea piazza, which can play host to sailing boats and small passenger ships. In La Maddalena, the large room which had been destined to host the summit is pointing out over the water– and allows for a wide view of all the islands in the archipelago. I like the idea that these buildings are both affected by the same kind of wind.

Far from the cities and the urban hinterland…

I also have strong links with those working class housing projects which I built in Seregno, on the edge of Milan, with Gianandrea Barreca and Giovanni La Varra, where we tried to work with variable shapes and forms around the theme of co-habitation, creating changeable spaces for families which can be increased and decreased, without incurring high costs. This project is almost the opposite of the Bosco Verticale (the vertical forest) which we have designed for the Isola neighbourhood, in Milan. This is an unusual project, highly experimental, which is destined for richer clients. It is a project which tries to strike a balance between technocratic rhetoric and the Branzian ideas we discussed earlier. Architecture has taken a back seat here, and what has become crucial is the question of the structure and engineering which can support and sustain trees in a building which is around 100 metres tall, and where the trees can be up to 12 metres tall on the top floor. This has been a real challenge, and I have enjoyed it a lot.

You sometimes need to have fun…

I was curious about this choice not to create architecture as a simple expressive form, and the idea of working with mechanical solutions to conceptual problems. How can we have an oak at that height? How can we support balconies made heavy by the soil needed for the trees to stay alive? How can a vertical forest made up of more than 1200 trees be built in the centre of Milan? The financier, Manfredi Catella, CEO of Hines Italia, was very doubtful, at the beginning, about this project. But in the end he accepted the risks involved. So, thanks to a kind of conscious extremism and the certainty that this could indeed be done, the Vertical Forest is being created as we speak.

KLAT is also interested in contemporary art: what do you think about the relationship between art and architecture?

It is a happy relationship, which I have utilised on many occasions, and sometimes in ways which were exaggerated or exploitative. I have always seen art as something which feeds into architecture. When Multiplicity was invited in 2002 to Kassel for Documenta 11, we were the only Italians there. That participation generated jealousies, ambiguities, misunderstandings almost as if we had wanted to do something which had nothing to do with us. In reality, I have never wanted to be an artist. Art has helped us carry out research and think freely. That said, I think that there are few contemporary artists who are doing really interesting work today. I can only think of a few names of people who are doing important artistic work today. These names include Hans Ulrich Obrist, a dear friend who thinks of himself as a curator but is instead a great contemporary artist. For years, Obrist has been travelling around the world accumulating and collecting interviews, contacts, conversations with players on the global cultural scene, in a way which is both semi-paroxystic and extremely fast, in order to create a kind of international archive of thought. For me, this concrete utopia is a necessary madness of extraordinary scope, carried out thanks to the work of one individual and his life. It represents a new form of Body Art. Hans uses interviews in order to set up networks, which then produce ideas. Much of the rest seems a little boring to me, and it often seems that artists are simply looking to provoke. And this is not to mention the relationship between art and fashion and art and design, which appears to me as a deathly embrace which shifts around the world – a pathetic and moving vanity fair.

Follow Paolo Priolo on Google+, Facebook, Twitter