(english text below)

A grande richiesta, abbiamo deciso di pubblicare sul sito le lunghe e straordinarie interviste apparse sul magazine cartaceo dal 2009 al 2011. Quaranta trascinanti conversazioni con i protagonisti dell’arte contemporanea, del design e dell’architettura. Una volta alla settimana, un appuntamento da non perdere. Un regalo.

Oggi tocca a Walter Niedermayr.

Paolo Priolo

Intervista di Susanna Legrenzi. Klat #03, estate 2010.

È il 2001, quando Eikon – l’El Croquis della fotografia – dedica a Walter Niedermayr un numero monografico. Il titolo è Raumfolgen, alla lettera “sequenze di spazi oppure conseguenze dello spazio”. A sorpresa, non ci sono le Alpi. Ma corridoi, tunnel sotterranei, ambulatori. Lavori seriali in strutture ospedaliere. Lo stesso sguardo in continuum che caratterizza l’indagine successiva: celle di prigione, istituto penale Berlino-Tegel, primavera 2003; Krems-Stein, autunno 2003; centro di detenzione giovanile di Gerasdorf, Vienna, 2004. Una di queste immagini, in grande formato, è nel suo studio a Bolzano. Un edificio moderno, nella prima cintura industriale, che in Alto Adige vuol dire un battito di ciglia dal tetto verde-oro del Duomo. Un open-space asettico: tavoli, plotter, una decina di libri. Sposti di 60 gradi lo sguardo e la montagna, che immaginavi lontana, è nuovamente lì: in un’opera, dietro la vetrata, nel suo ultimo progetto sull’Iran, dove paesaggi color sabbia cedono al bianco ottico di una stazione sciistica. Riannodi il filo del discorso: ci sono le Alpi, le celle, il dialogo serrato con lo studio giapponese SANAA. Ma soprattutto, c’è un’indagine che coltiva un’unica ossessione: lo spazio secondo Walter Niedermayr.

È la prima volta che vedo uno studio così ostinatamente ordinato: da quanto tempo ci lavora?

Quattro, cinque anni.

Come si svolge il lavoro in studio?

Non trascorro molto tempo in studio, vengo per qualche ora, ogni giorno. Presidia Patrick, il mio assistente che lavora le immagini.

Quando non è in studio?

Seguo i miei progetti.

Francesco Jodice, in un’intervista, diceva che la condizione del fotografo ricorda il protagonista di un quadro di Caspar David Friedrich: una persona sola sul ciglio della montagna…

Forse cent’anni fa (sorride, nda). Oggi, ovunque vada c’è gente. Non mi trovo mai solo, accade raramente anche quando parto in solitaria per la montagna.

Come è arrivato alla fotografia?

Sono un autodidatta, non ho seguito un’istruzione specialistica. Da giovane ho lavorato in Germania, alla Siemens, nel reparto tecnico: elettronica, computer, hardware. In quegli anni, avevo già iniziato a fotografare. Avevo un forte interesse anche per i film sperimentali. Purtroppo, in quel periodo per motivi economici non ho approfondito.

In che anni siamo?

1975-’77. L’anno successivo sono rientrato a Bolzano. Ho lavorato in un’azienda software e ho continuato a interessarmi di fotografia, ma senza fretta.

Il suo primo progetto fotografico?

Il primo di una certa importanza è una ricerca in Alto Adige su una miniera d’argento, un luogo storicamente rilevante all’epoca dei Fugger di Augusta, che dalla Germania avevano potere europeo sulle miniere. Ho documentato il sito, analizzando il retroterra sociale. Le immagini erano ancora in bianco e nero.

Con quale macchina ha iniziato a scattare?

Una 6×7, manuale.

Sviluppava in camera oscura?

In quella stagione sì. Ancora oggi a casa ho una camera oscura, che però non uso più.

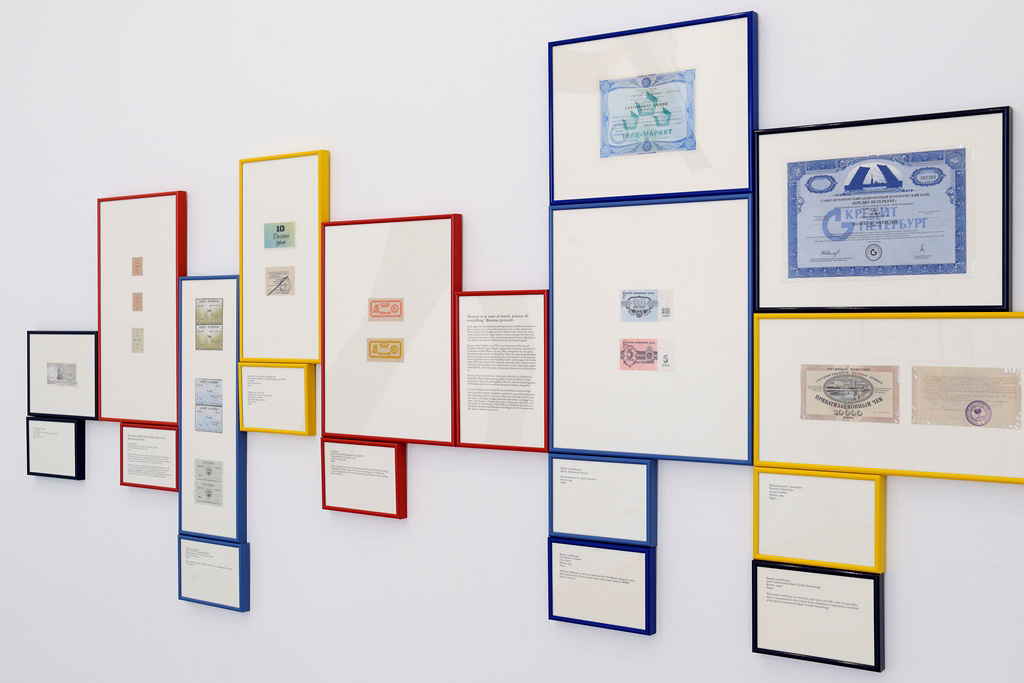

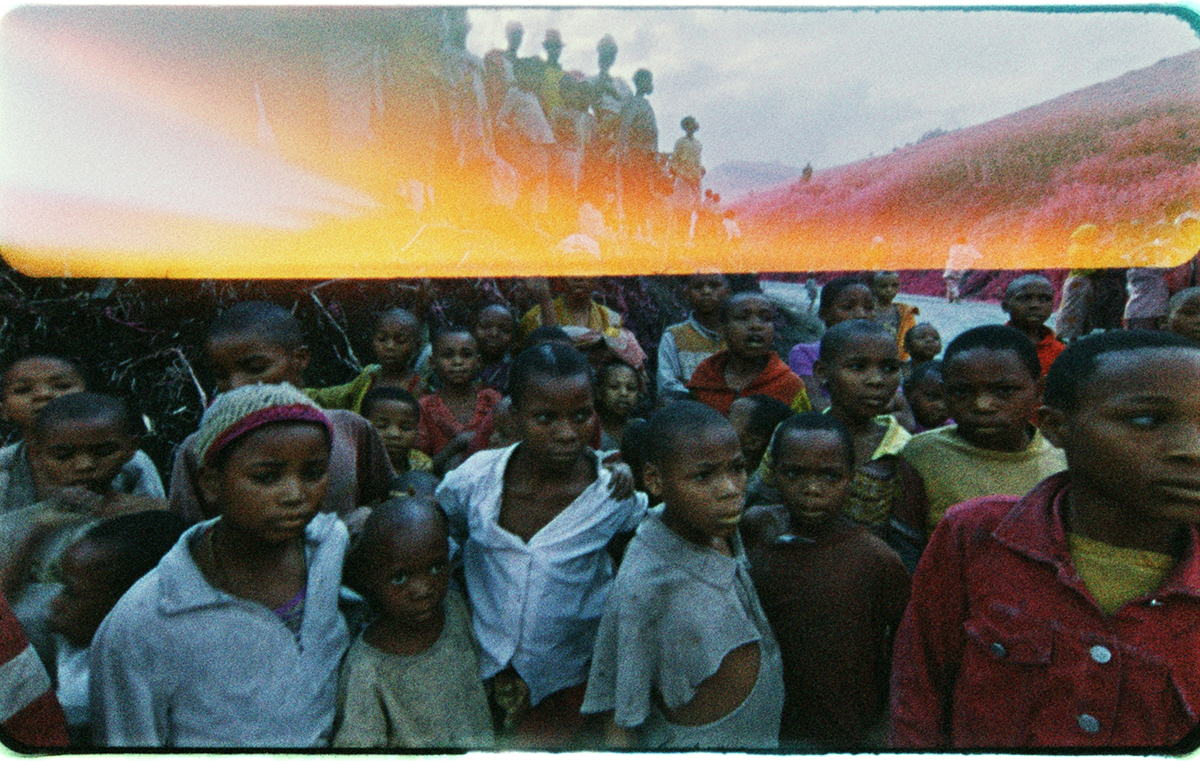

![Walter Niedermayr, Nigardsbreen, 1/2002.]()

Walter Niedermayr, Nigardsbreen, 1/2002. Courtesy: Galleria Suzy Shammah, Milano e/and Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin/Stockholm

Nostalgia?

Mi piaceva, ma era complicato. Si stava lì notti intere a sviluppare, stampare, ingrandire. Mi ci sono cimentato da solo: ero affascinato, volevo capire come funzionava il processo. Oggi lavoro ancora in analogico, uso la pellicola, ma poi procediamo con la scansione, la lavorazione in digitale, quindi le stampe. Pochi anni ed è cambiato tutto.

Ansel Adams, un grande vecchio della fotografia, ha detto: «Spesso ho pensato che se la fotografia fosse “difficile” nel vero senso della parola – nel senso cioè che la creazione di una semplice fotografia richiedesse lo stesso tempo e la stessa fatica di un buon acquerello o di una buona incisione – il salto qualitativo della produzione media sarebbe enorme. L’assoluta facilità con cui possiamo produrre un’immagine banale porta spesso a una totale mancanza di creatività». Concorda?

Dipende da cosa si vuole fare con il mezzo fotografico, da come lo si usa. La tecnica non mi ha mai dato problemi. Sono riuscito a imparare da solo. Certo, ho conosciuto anche diversi fotografi. Per esempio, si è rivelato fondamentale l’incontro con Lewis Baltz, uno dei protagonisti della stagione del New Topographic. Le sue ricerche sul paesaggio hanno influito sul mio lavoro; in particolare, il progetto Park City, realizzato nei primi anni Ottanta, vicino a Salt Lake City, la seconda casa degli americani: detriti, edifici in costruzione, la devastazione del territorio. Anni fa sono andato a visitare quella regione in America, ero molto curioso di vedere come era cambiata. Di Baltz mi affascinano anche i lavori più recenti, il suo linguaggio è ancora molto contemporaneo. Un altro che mi interessava era Stephen Shore.

Sia Baltz sia Shore hanno lavorato sul paesaggio. In tempi meno sospetti, persino Vermeer ha usato la camera oscura per molti dei suoi dipinti, di certo per la Piccola strada di Delft, riproducendo sulla tela ciò che realmente appariva ai suoi occhi. Che rapporto ha con la realtà che fotografa?

Penso che l’immagine sia una cosa a sé: la fotografia, alla fine, è una superficie bidimensionale. C’è una relazione tra ciò che fotografiamo e la realtà, ma quella che ci racconta l’immagine è un’altra realtà ancora. Si tratta di una trasformazione del visibile. Da sempre sono affascinato dal rapporto tra realtà dello spazio e realtà dell’immagine.

Germania, Italia. Tecnologia e informatica: un universo astratto, matematico. Che cosa l’ha spinta a misurarsi con il paesaggio fisico?

Iniziare a lavorare sul paesaggio alpino è stato piuttosto ovvio, visto che le montagne costituiscono una topografia a me molto vicina, che mi ha sempre incuriosito. Da piccolo ci andavo spesso con mio padre, è il paesaggio che mi circonda. Il mio interesse per le Alpi è nato dal cambiamento della missione di questi luoghi. Con gli anni, molto è cambiato. Il turismo ha avuto uno sviluppo strepitoso.

Inquadrare è il modo più semplice di eliminare qualcosa dal nostro campo di percezione retinica. Con l’inquadratura si ritaglia una finestra sul reale. Talvolta è una porzione motivata di un intero. Che cosa resta al di fuori?

Penso che ogni immagine sia solo un frammento di una cosa molto più complessa. Di uno scenario, cerco di inquadrare ciò che più m’interessa: il paesaggio che viene usato dall’uomo, che viene strutturato. Il paesaggio puro, senza riflessi umani, mi affascina poco. Forse non esiste nemmeno più, l’uomo è già stato dappertutto.

L’evento che contribuì più di altri a dare avvio a un radicale cambiamento della fotografia italiana fu Viaggio in Italia di Luigi Ghirri. Era il 1984. Il progetto, una mostra e un libro, coinvolgeva una schiera di giovani fotografi: Gabriele Basilico, Mimmo Jodice, Guido Guidi, Mario Cresci, Roberto Salbiati, Olivo Barbieri, Vincenzo Castella e Giovanni Chiaramonte. Che tipo di legame ha con quella stagione?

Sicuramente è stata una stagione molto importante, che in qualche modo, forse, mi ha anche influenzato. Oggi, però, il modo di pensare la fotografia è un po’ cambiato. Penso che fotografare il paesaggio con l’intenzione di realizzare un documento puro non abbia più il senso di una volta.

Se dovessimo cercare l’origine di questo interesse rivolto al paesaggio, un’importanza notevole l’hanno avuta gli Alinari, Giuseppe Pagano e Paolo Monti, Mario Sironi. Ma anche l’opera dei grandi americani, da Walker Evans a Lee Friedlander, Robert Frank, William Eggleston. Guardando all’Europa, sono da citare Bernd e Hilla Becher, con la loro catalogazione di elementi di architettura industriale. Con un passato così denso, c’è ancora modo di superare la “tradizione”?

Quando ho fatto il mio primo lavoro in serie, nel 1987, mi sono chiesto se aveva senso rinunciare a lavorare intorno a un’immagine singola, che in quanto singola diventa poi un’icona. La verità è che ciò che vediamo a livello retinico non è mai un’unica immagine, ma più punti di vista. Ecco la serialità. Con questo metodo, ho cercato di andare in un’altra direzione. Credo anche che in ogni scatto includiamo quello che ci portiamo dentro: la cultura, la percezione primaria, tutto ciò che alimenta la nostra stessa storia. È solo con questa attrezzatura pesante che realizziamo le immagini. Se vediamo la fotografia da questa prospettiva, ogni autore ha una sua specificità di sguardo che va oltre le scuole, oltre la tradizione.

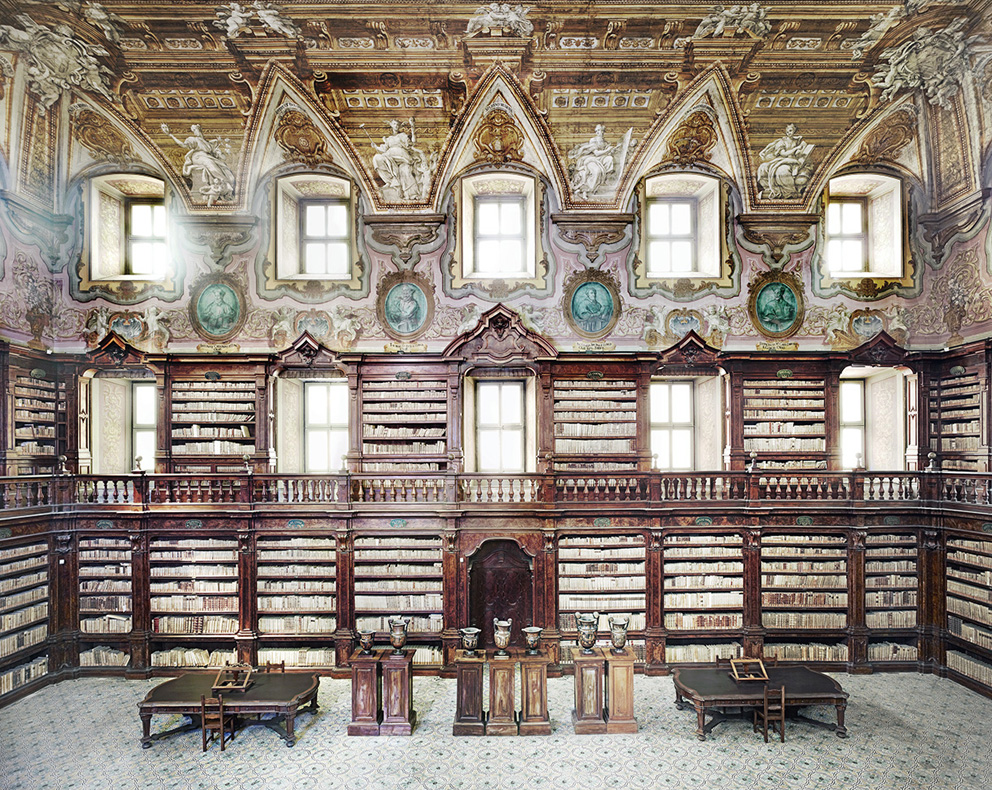

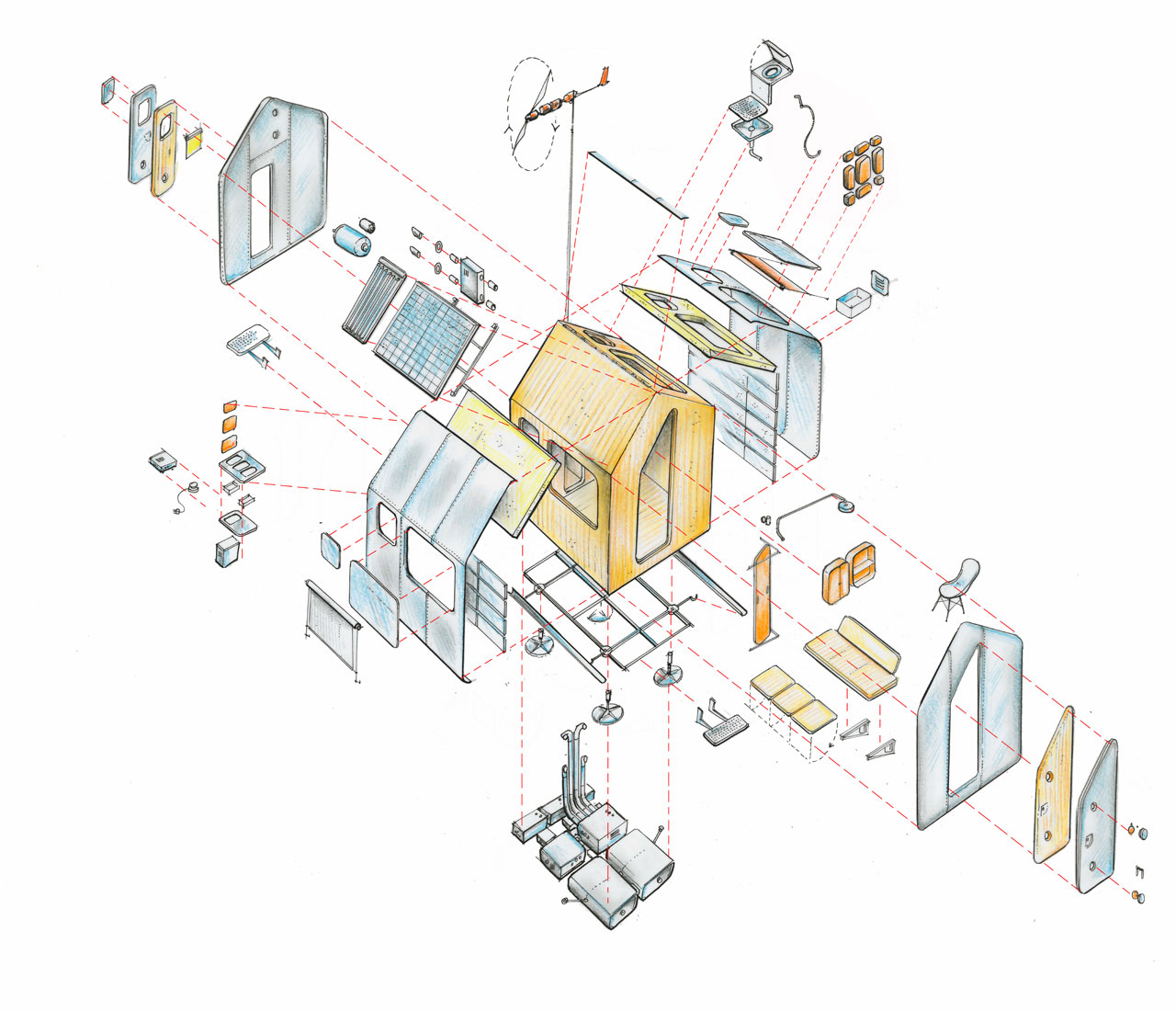

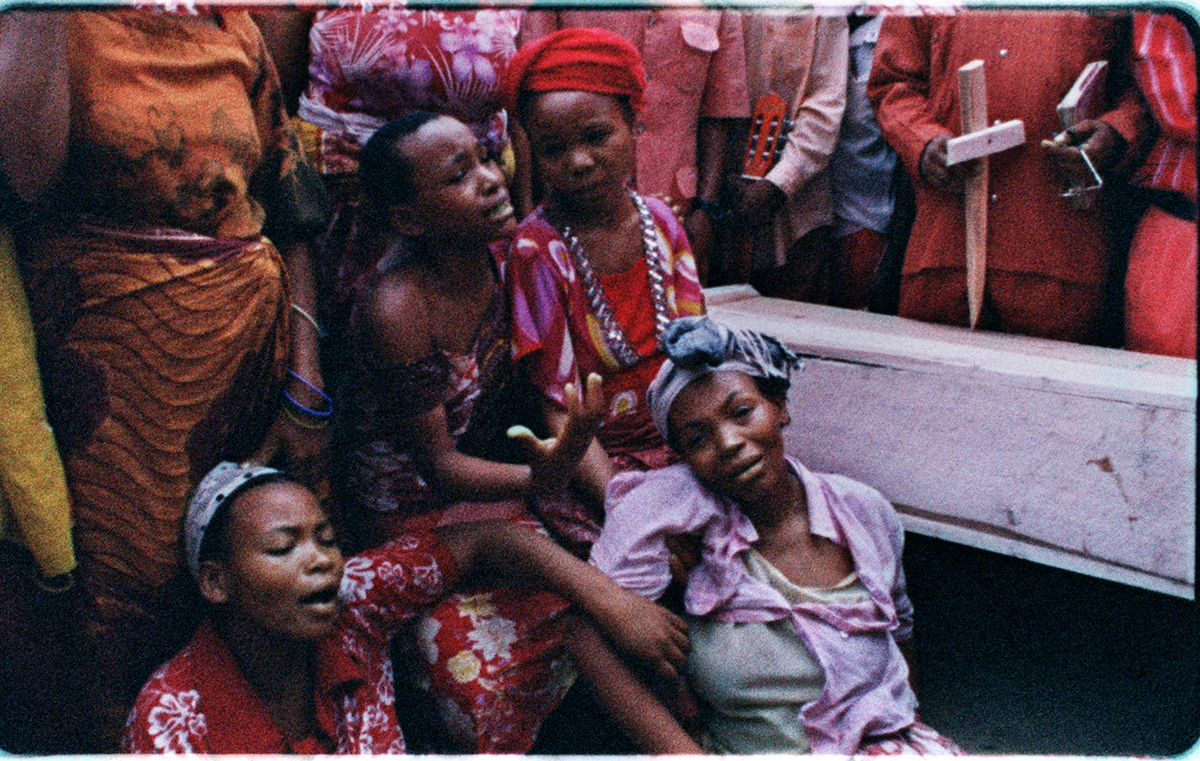

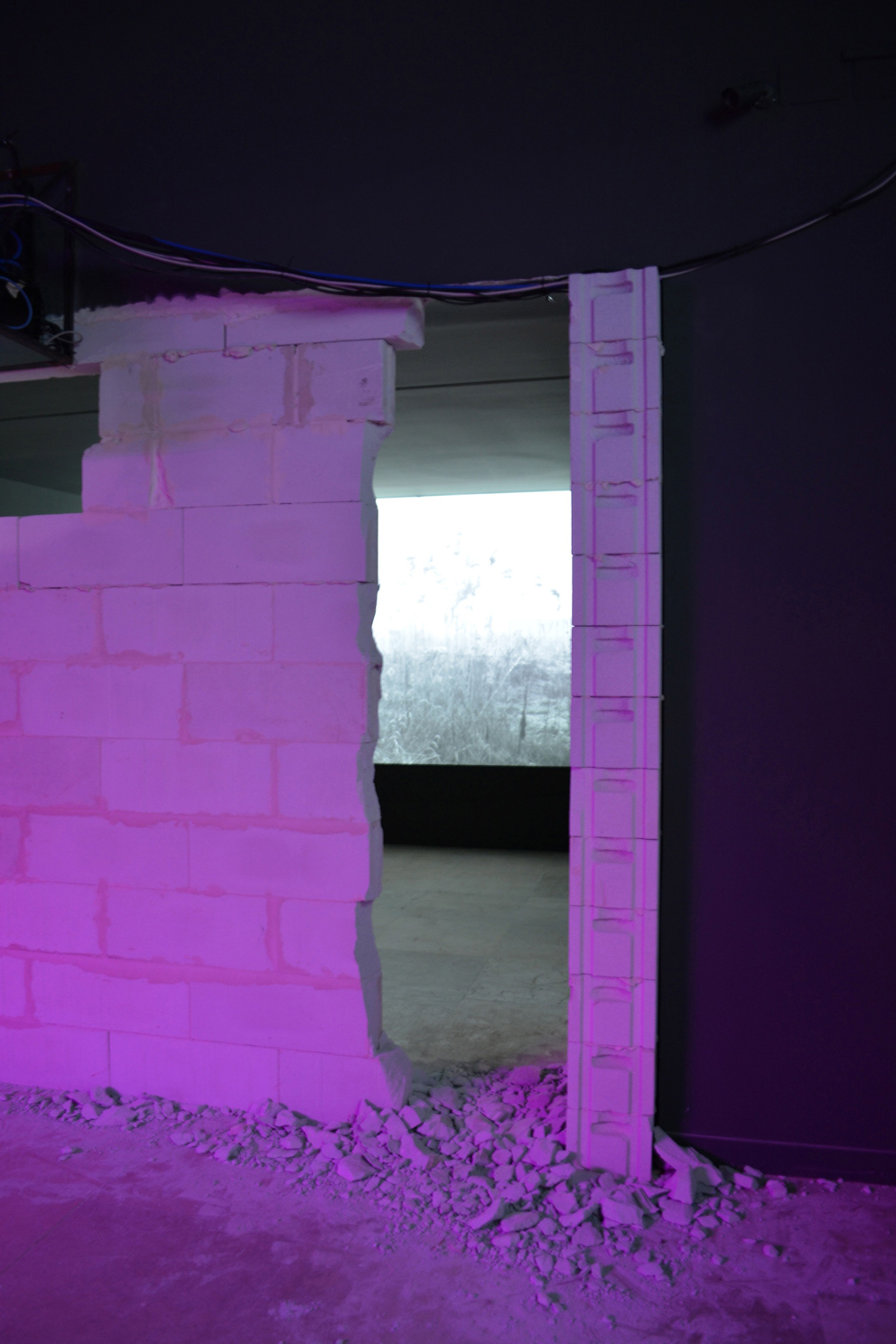

![Walter Niedermayr, Raumfolgen, 159/2005.]()

Walter Niedermayr, Raumfolgen, 159/2005. Courtesy: Galleria Suzy Shammah, Milano e/and Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin/Stockholm.

Superare la tradizione è anche contemplare la presenza di un paesaggio umano. Un aspetto che molta della fotografia di landscape continua a tralasciare.

Una certa fotografia coltiva l’ossessione di restituire spazi puliti, senza persone. Il landscape e l’architettura, o semplicemente lo spazio, esistono con le persone: se non ci sono persone non c’è spazio. Nei miei lavori sulla montagna, la presenza di persone è essenziale: la gente dà una idea delle dimensioni, ci dice dove si trova, quanto è grande una superficie. È un parametro di riferimento.

Baudelaire diceva che la fotografia è la palestra dei pittori mancati. Ancora oggi, il rapporto tra arte e fotografia è controverso. Persino il reportage di guerra diventa oggetto di mostre in luoghi solitamente votati all’arte.

Vedo la fotografia come un mezzo a disposizione dell’arte, che può essere arte o meno: dipende da ciò che l’artista o il fotografo realizza con questo mezzo, dalla ricerca che porta avanti. Chi poi definisce cosa è arte e cosa non lo è, è un’altra questione. Personalmente, non so se io faccio arte, non l’ho mai detto. Certo, poi c’è il mercato…

Contemporaneità in fotografia.

La fotografia contemporanea si definisce in base al rapporto che ho con il mondo contemporaneo. Si relaziona con il modo in cui mi muovo, con le cose che faccio. Oggi il rapporto con il paesaggio forse è diventato più diretto, immediato. Non c’è più l’atteggiamento contemplativo di una volta, alla Caspar David Friedrich. Il mio interesse per il mezzo fotografico è rendere visibile ciò che, in parte, può andare oltre la normale rappresentazione. La fotografia non può sostituire l’aura dell’originale, cosicché s’interroga sul proprio ruolo, come mezzo di espressione: si chiede cosa può rilevare e rivelare, senza avanzare pretese di verità.

Tra i suoi lavori più recenti, c’è anche il one-to-one con lo studio giapponese SANAA, di Kazuyo Sejima, direttore della prossima Biennale d’Architettura di Venezia, e Ryue Nishizawa. Come vi siete avvicinati?

Li conoscevo dagli anni Ottanta. Già allora sembravano architetti molto interessanti. Alla fine del 1990 ho ricevuto una mail dallo studio. Avevano trovato un mio libro in Spagna e chiedevano di incontrarmi a Tokyo per farmi vedere le loro architetture. In quel periodo avevo in preparazione una mostra in Giappone. Ci siamo trovati, condividendo poi interessi molto simili.

Che cosa la attrae dell’architettura di SANAA?

È un’architettura molto essenziale, apparentemente semplice, ma di una semplicità complessa, con una tendenza a relativizzare il rapporto tra forma e contenuto, rimanendo sempre molto funzionale. Non è mai spettacolare, anche se lavorano sempre al limite della realizzabilità. Nel loro caso, si tratta di una sorta di ambivalenza dell’architettura, sottolineata dall’uso del vetro e della trasparenza. Anch’io cerco nella fotografia di sfidare il limite, quello del visibile, della rappresentazione. È un aspetto centrale del mio lavoro.

Walter Benjamin ha sostenuto che è più facile cogliere un’architettura mediante la macchina fotografica che non nella realtà. Che cosa accade quando l’architettura è vista da un artista?

SANAA non mi ha mai considerato un fotografo documentarista. A me interessa restituire una percezione soggettiva, che è propria dell’immagine. Il mio modo di lavorare in senso seriale si oppone alla tradizionale concezione di spazio statico e rende forse l’idea dinamica del percorso percettivo. Già dall’inizio, era chiaro che i miei non erano scatti di documentazione, ma ricerche sulle loro architetture. Tra i progetti di SANAA che più mi hanno affascinato c’è sicuramente il 21st Century Museum a Kanazawa, il Padiglione del Vetro del Museo d’Arte di Toledo, in Ohio, e l’ultimo progetto, il Rolex Center a Losanna, in Svizzera, forse il più interessante tra tutti. A colpirmi, è stata la sperimentazione di un nuovo modo di intendere il movimento all’interno di in uno spazio: l’esperienza diretta del luogo è diversa dalla percezione che se ne ha. È un po’ come passeggiare su un paesaggio collinare…

Ruff ha indagato per anni su Mies van der Rohe: ci sono architetture iconiche con le quali le piacerebbe dialogare?

Non saprei. Quello di Ruff è un altro approccio. Mies van der Rohe fa ormai parte della storia dell’architettura, è un classico. Il lavoro di SANAA è molto contemporaneo. Sejima e Nishizawa vivono e progettano adesso, con un modo per certi versi molto democratico.

Immagino che sia stato nel loro studio a Tokyo: com’è sopravvissuto al caos creativo che vi regna?

Lì è il Giappone. Per noi europei può sembrare caotico, ma si ha comunque la sensazione di un ordine molto sistematico. Sono in molti e lavorano in spazi molto ristretti. Tutto ciò richiede molta disciplina e reciproco rispetto. Ultimamente hanno cambiato studio, ma l’atmosfera è la stessa: venti, trenta persone che lavorano tutte insieme, giorno e notte. Un flusso di energie che diventa più calmo in certi momenti, grazie alla presenza mitigante di un certo numero di assistenti europei, che di natura hanno altri ritmi. È un altro modo di intendere la professione, anche Kazuyo non si risparmia. Per noi europei è un’esperienza molto diversa, quasi stordente.

SANAA Tokyo, Niedermayr Bolzano: come mai ha scelto di vivere lontano da quelli che comunemente sono indicati come epicentri?

Credo che i centri siano quelli che noi stessi eleggiamo come tali. Oggi, se siamo interessati a delle cose, a delle esperienze, possiamo comunque facilmente raggiungerle, possiamo informarci. Chiaramente, ci sono luoghi dove c’è più movimento: Berlino, Londra, New York. Alla fine, qui a Bolzano la qualità della vita non è male. A volte, se mi sento isolato, parto. Sono spesso in giro. Mi piace fermarmi per un certo periodo in un altro luogo e poi tornare.

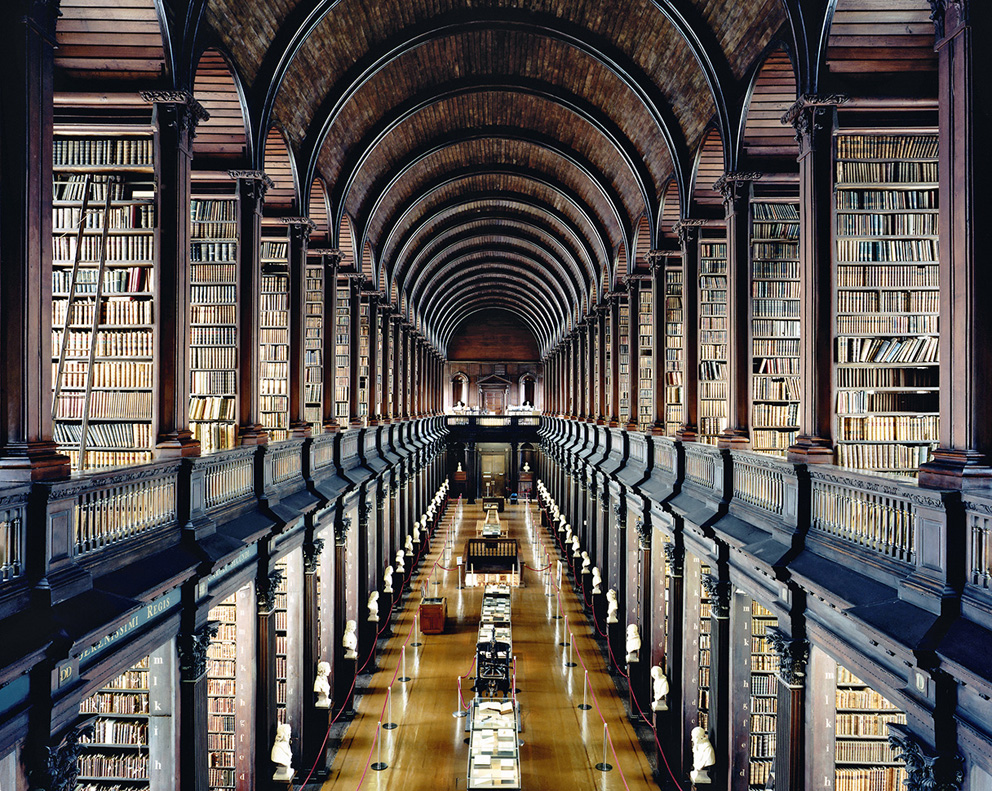

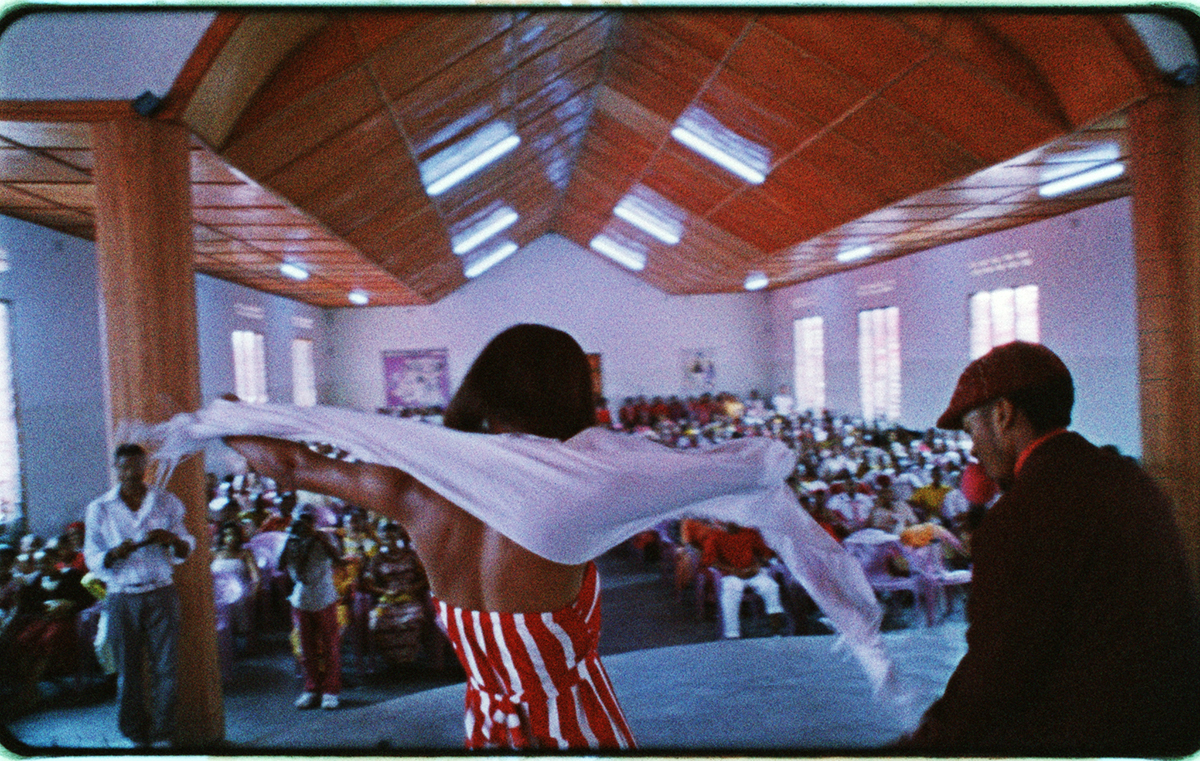

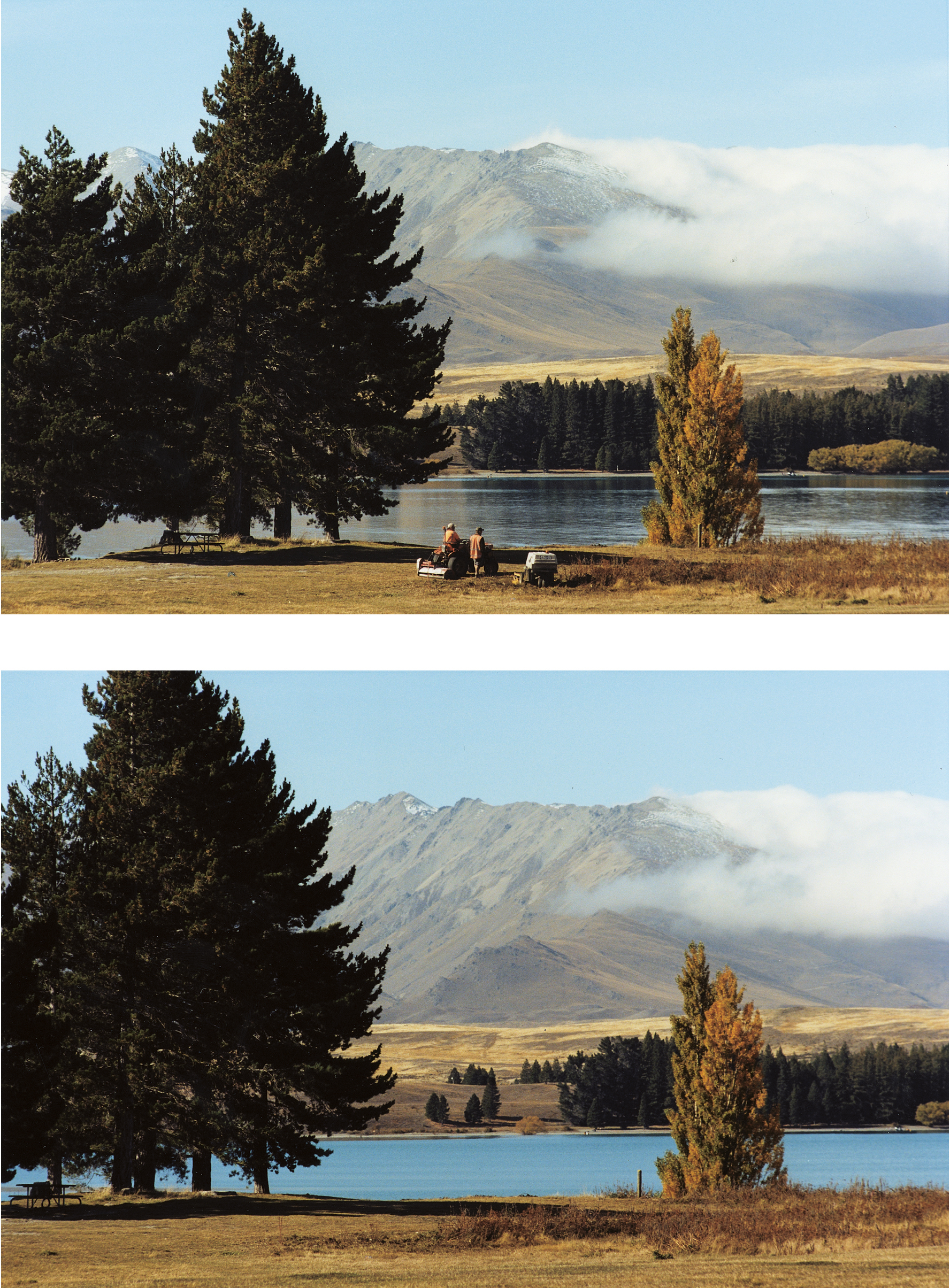

![Walter Niedermayr, Kitzsteinhorn, 32/2007.]()

Walter Niedermayr, Kitzsteinhorn, 32/2007. Courtesy: Galleria Suzy Shammah, Milano e/and Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin/Stockholm.

Da anni la fotografia di ricerca si esprime sempre in un formato extralarge, quasi fosse il formato stesso a legittimarne l’aura. Che importanza ha il formato nella fotografia contemporanea e nello specifico nel suo lavoro?

Il formato è sicuramente una cosa da decidere con precisione, senza necessariamente tener conto della dittatura del mercato. All’inizio, credo che il grande formato sia stato un po’ il modo per scappare dal rettangolo fotografico e un po’ la scorciatoia per andare incontro al mondo dell’arte. Nella mia ricerca, il formato dipende dal contenuto dell’immagine. Inoltre, considero anche il rapporto con lo spazio dove verrà esposta l’opera. Da questo punto di vista, posso decidere di stampare anche in formato molto piccolo. Occorre vedere come si vuole costruire la propria mostra. Alle sue spalle c’è un dittico che fa parte della ricerca sulle prigioni: quella stessa immagine l’ho usata in formato molto piccolo, a New York, e in dimensioni extralarge in altri contesti. Dipende dalla situazione.

Dal formato alle tirature. Sempre secondo Thomas Ruff, la tiratura è piuttosto comoda. È un modo per considerare chiuso un lavoro. E fa salire i prezzi. Per lei?

Io faccio edizioni da 6. Chiaramente, il prezzo cambia avendo preso questa decisione. Quando le sei copie di un lavoro sono stampate l’edizione è chiusa. Certo, la fotografia ti offre la possibilità di fare immagini in eternità, ma una scelta del genere richiede altri contesti.

Mercato, quotazioni, gallerie. Che aria tira in questo momento?

Credo che gli artisti dovrebbero essere più autonomi, facendo anche progetti al di fuori delle gallerie e dei circuiti dell’arte. La galleria ha un ruolo di primo piano se si considera responsabile non solo nei propri riguardi, ma anche nei confronti dell’artista, favorendone lo sviluppo. In periodi economicamente difficili come questo, le qualità di un gallerista diventano evidenti. Io forse ho avuto fortuna, essendo entrato nel circuito anni fa. Sento però di altri artisti che hanno problemi con le gallerie, che in questo periodo spariscono o investono meno.

Lei ha una galleria a New York, una a Milano, a Stoccolma e a Berlino.

Come dicevo, non mi lamento.

Come lavora a una mostra?

Parto sempre dallo spazio, cioè da una pianta, e mi faccio delle idee su quello che si potrebbe fare. Una volta ho sperimentato l’uso di rendering. Ho provato, ma ho scoperto che funziona poco e alla fine ho cambiato tutto. Mi basta la carta, con quella riesco a immaginare. Per ora ho esposto sempre opere in gran parte inedite. Non ho fatto ancora retrospettive. Ogni mostra monografica richiede un impegno di circa sei mesi. Anche se alla fine devo ammettere che per chiudere un lavoro devo avvertire il peso di una certa pressione…

Parliamo di libri.

Rispetto a una mostra, un libro è un’altra cosa. Un’altra percezione. Mi interessa molto. Cerco di lavorare con grafici che percepiscono il mio modo di lavorare. Spesso c’è molta difficoltà a comprendersi: a volte ho l’impressione che il lettering non dialoghi in armonia con le immagini. Per Walter Niedermayr/SANAA ho lavorato con un grafico olandese: all’inizio abbiamo avuto molte discussioni, incomprensioni. È stato un percorso piuttosto impegnativo: alla fine è venuto fuori un bellissimo libro.

Come procede all’editing?

Prima cerco di organizzare un nucleo di immagini, quindi cerco di dare loro una sequenza. Le porto a casa, le stendo per terra, le giro e rigiro, fino a farle funzionare. Poi, ecco: arriva il grafico e vuole cambiare le cose. È un processo continuo di cambiamenti, un andarsi incontro con delle idee.

Come si difende dall’iperproduzione d’immagini che ci circonda?

Mi concentro sulle mie immagini, sul mio modo di vederle. Per difendersi occorre anche essere molto rigorosi nella loro scelta e non produrre all’infinito. Anche facendo meno libri. La moltiplicazione di immagini tramite libri porta a un’inflazione. Un’altra possibilità potrebbe essere anche quella di essere molto radicali. Basterebbe, forse, interrogarsi continuamente sul senso del proprio lavoro.

Quanti libri ha pubblicato?

In 20 anni ho fatto 9 monografie.

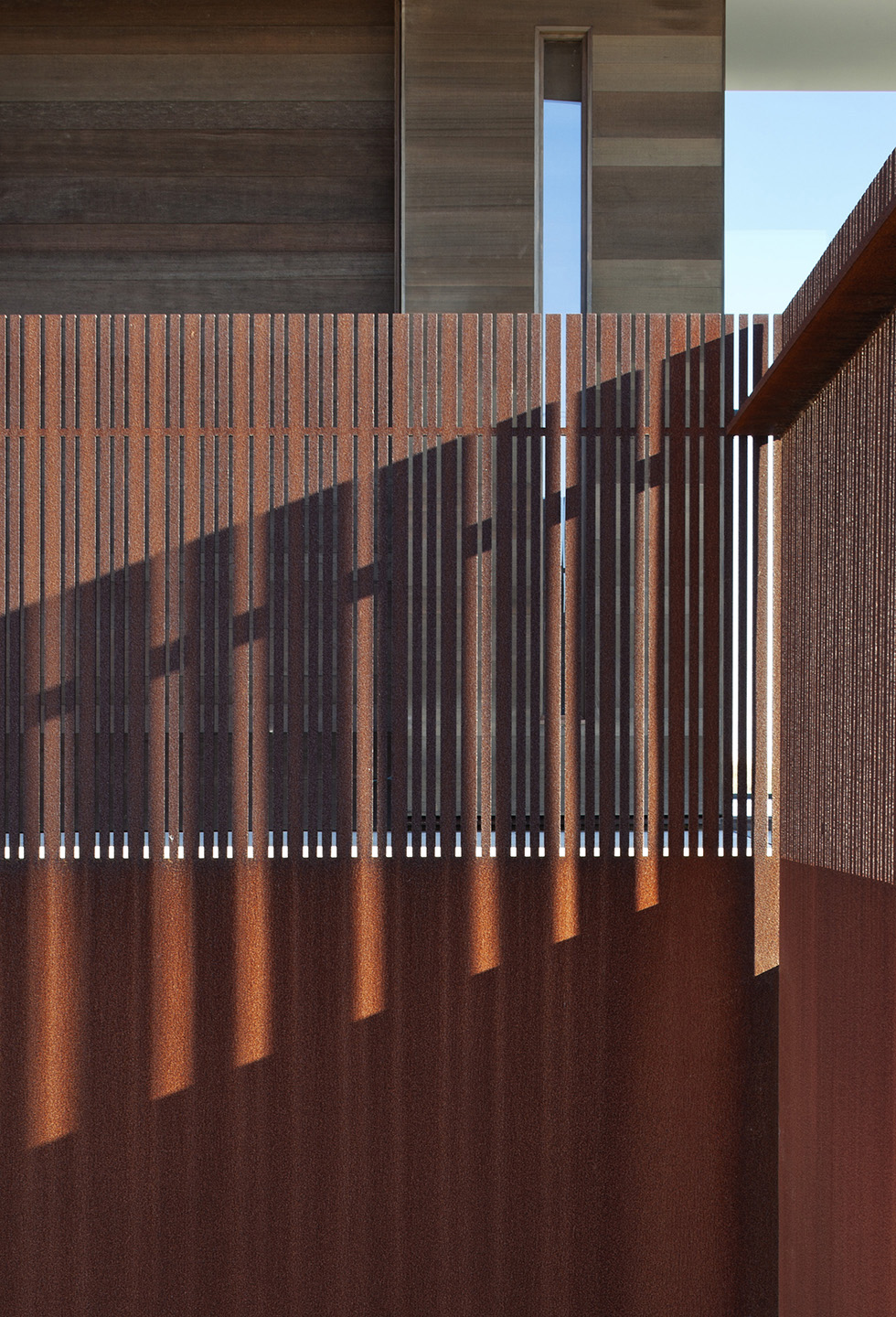

Tra i recenti c’è Station Z: Memorial Sachsenhausen, Walter Niedermayr/HG Merz.

Stazione Z è il nome del forno crematorio del campo di concentramento di Sachsenhausen, uno dei primi campi nazisti. Tra il 1936 e il 1945 a Sachsenhausen furono rinchiuse più di 200.000 persone di circa 40 nazionalità diverse. Anni fa, l’architetto tedesco HG Merz ha progettato un memoriale: una struttura astratta, quasi una lamina che protegge le tracce del luogo. Quando mi è stato chiesto di lavorarci, per me è stato importante capire quale sarebbe stato il periodo giusto. Ci sono stato a gennaio, c’era abbastanza freddo, una certa luce, una certa atmosfera per poter fare questo lavoro. Prima di iniziare a fotografare, ho fatto due sopralluoghi per capire meglio quale fosse la sua storia, il contesto, come mai fu scelta questa zona, a soli 35 chilometri a Nord di Berlino.

Restituire un luogo come questo, con una carica storica ed emotiva così importante, attraverso una immagine esteticamente complessa e ricercata non può generare un corto circuito?

È lo stesso interrogativo suscitato da ricerche come quella sulle prigioni. Ci sono dei luoghi dove per me è molto difficile stare. Dopo tre giorni a Sachsenhausen, ho avuto la sensazione che il luogo esprimesse comunque ciò che era stato. Anche se non si vedono più le tracce, è impossibile non sentirle, sono nell’atmosfera. Ogni passo che fai, non puoi prescinderne.

Che rapporto ha con il colore? Negli anni i suoi lavori hanno subito una graduale desaturazione.

Sul colore c’è una discussione infinita. Già quando ho cominciato a fotografare, e usavo il bianco e nero, avevo l’impressione che il mondo della fotografia fosse troppo pieno di contrasti. Dopo aver scoperto il lavoro di Timothy O’Sullivan, che mi ha colpito per via di quel suo bianco e nero così morbido, la desaturazione del colore mi è parsa più naturale, più vicina a quello che percepiamo. Ora mi accorgo che spesso mi spingo oltre, rasentando il limite. È come se cercassi una distanza sempre più grande dal concetto un po’ datato della saturazione che, a ben vedere, è un dettato dell’industria che ci dice: così sarebbe giusto, si vende meglio. Amo i colori neutri, mi piace più un bianco freddo che caldo. Lavorando sui paesaggi montani ho spesso il bianco: preciso, pulisce e dona equilibrio a tutti gli altri colori.

Oggi con il digitale, Photoshop, il plotter, l’occhio si è abituato a immaginare/vedere un risultato che si concretizza in immagini dopo almeno tre passaggi. Accade anche nell’editoria: prima c’è il monitor del computer che ci restituisce l’immagine in un modo, poi ci sono i cromalin, quindi la stampa su carta. Con tutti questi passaggi, l’occhio si è abituato a misurarsi con 3 “inganni”. Che cosa vede e che cosa immagina Niedermayr quando guarda il mondo attraverso l’obiettivo?

Credo che già in camera oscura ci fossero molte possibilità di manipolazione. Oggi con il digitale queste possibilità si sono semplicemente moltiplicate. Si può fare di tutto. Poi bisogna vedere che cosa si vuole fare. Per me non cambia molto. Cambia nel senso che non devo più usare la chimica richiesta dai bagni per lo sviluppo. Lo stesso vale anche per il colore: ieri lo si poteva filtrare in analogico, oggi c’è Photoshop che ha potenzialità altissime.

A cosa sta lavorando adesso?

Sto preparando una pubblicazione con alcuni lavori che ho realizzato in Iran. Ci sono stato tre volte: nel 2005, 2006, 2008. Ho fotografato il paesaggio della città storica e moderna. Non solo a Teheran, ma anche in altri centri: Esfahan, Shiraz, Yazd e in altri.

È la prima volta che si misura con un paesaggio così distante?

Non proprio, ho lavorato anche in America, in Giappone, in Nuova Zelanda. Il progetto in Iran è stato organizzato da un istituto di Vienna che si occupa di scambi culturali con l’Iran. Sono coinvolti artisti, architetti, scrittori che presentano le loro ricerche, conducono workshop e infine possono lavorare fino a quattro settimane nel paese, che è un luogo bellissimo, molto interessante. Quello che sentiamo dell’Iran è molto distorto dalla politica. La politica in Iran è una cosa, la popolazione un’altra. La maggior parte della generazione dei trentenni vorrebbe andarsene via o cambiare il sistema, è una realtà difficile, complessa.

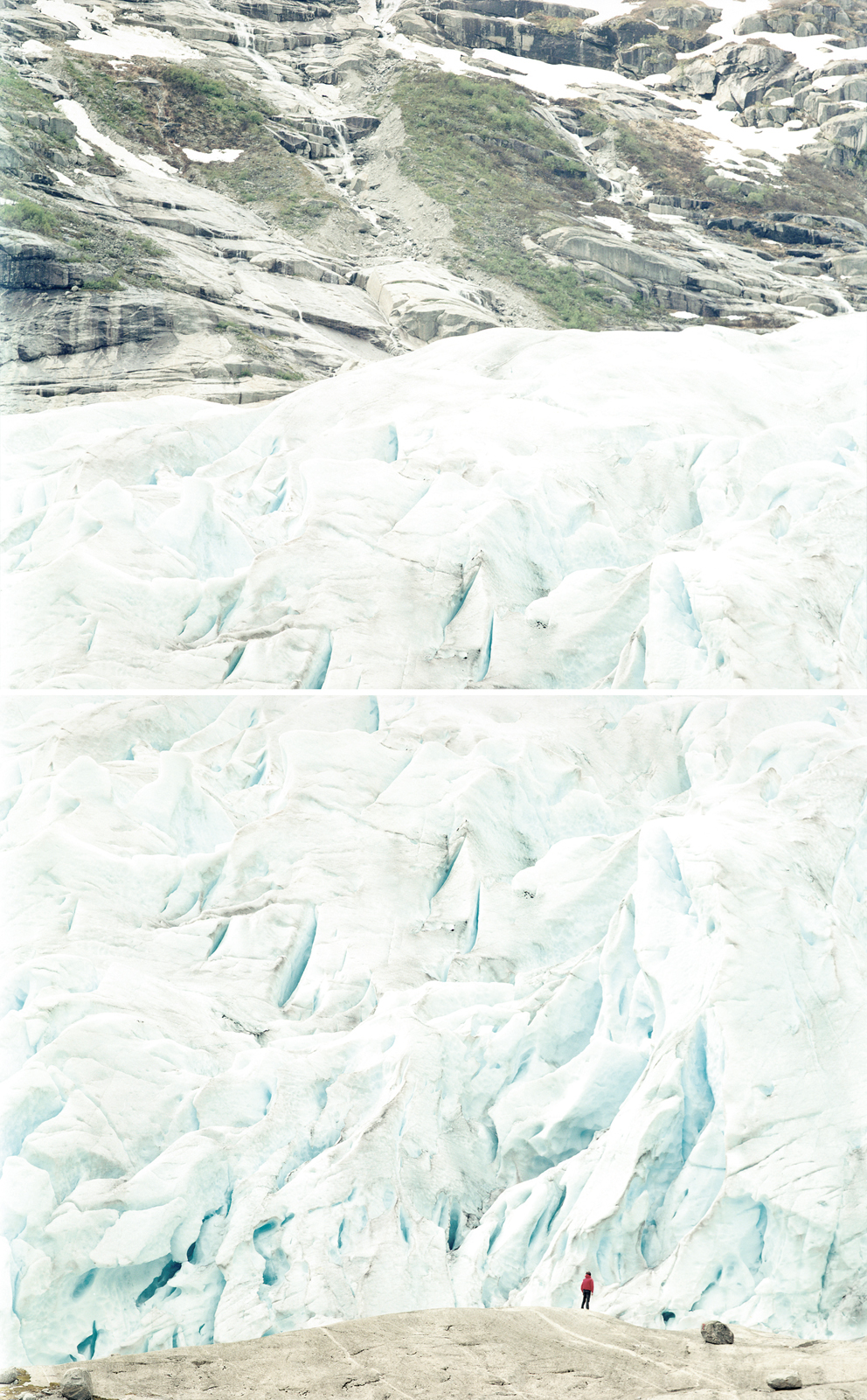

![Walter Niedermayr, Raumfolgen, 236/2007.]()

Walter Niedermayr, Raumfolgen, 236/2007. Courtesy: Galleria Suzy Shammah, Milano e/and Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin/Stockholm.

Che libro sfoglieremo?

La ricerca ha a che fare con il nuovo che si è inserito nella tradizione. Mi interessava molto questa ambivalenza: da un lato c’è una storia lunghissima, di tremila anni e anche più, che abbraccia diversi periodi, epoche e culture, anche architettoniche. Una tradizione estremamente affascinante. Penso, per esempio, alle torri del vento iraniane, edifici semplici e al tempo stesso sofisticati dal punto di vista bioclimatico. Dopo la rivoluzione islamica, il passato recente ha introdotto un’idea di architettura che ha prodotto paesaggi senza connessioni con la storia. Questo contrasto mi ha molto colpito. È come se la forza escludente del regime avesse imposto l’abbandono della tradizione, suggerendo involontariamente di guardare a Ovest in cerca d’altri modelli.

Ci fa vedere qualcosa?

Niedermayr apre un libro a caratteri arabi. Sfoglia e ci mostra le ricerche di una decina di autori. Vedi Teheran, le costruzioni di terra, l’Iran monumentale, quartieri sfarinati, periferie scolorite. Poi a sorpresa, il bianco ottico di una stazione sciistica. E, ancora una volta, tutto torna.

/

In response to great demand, we have decided to publish on our site the long and extraordinary interviews that appeared in the print magazine from 2009 to 2011. Forty gripping conversations with the protagonists of contemporary art, design and architecture. Once a week, an appointment not to be missed. A real treat. Today it’s Walter Niedermayr’s turn.

Paolo Priolo

Interview by Susanna Legrenzi. Klat #03, summer 2010.

In 2001 Eikon – the El Croquis of photography – did a special issue on Walter Niedermayr. The title was Raumfolgen, literally “sequences of spaces or consequences of space.” Surprisingly enough there were no Alps. Just corridors, underground tunnels, clinics. Series of pictures taken in health care facilities. The same continuum gaze found in the next study: prison cells, Berlin-Tegel penitentiary, spring 2003; Krems-Stein, fall 2003; Gerasdorf youth detention center, Vienna, 2004. One of these images, in a large print, hangs in his studio in Bolzano. A modern building, in the first industrial belt, which in Alto Adige means the blink of an eye from the green-gold roof of the cathedral. An aseptic open space: tables, plotters, a dozen books or so. Shift your gaze by sixty degrees and the mountains, which you had imagined distant, are back: in a work, behind the glazing, in his latest project on Iran, where sand-tone landscapes yield to the optical white of a ski resort. You tie up the threads of the discussion: the Alps, the cells, the intense dialogue with the Japanese studio SANAA. But, above all, there is research that pursues a single obsession: space, according to Walter Niedermayr.

This is the first time I’ve seen such an orderly studio: how long have you been working in here?

Four or five years.

How does the work happen in this studio?

I don’t spend much time here, I come for a few hours every day. It’s run by Patrick, my assistant who works on the images.

And when you’re not in the studio?

I work on my projects.

Francesco Jodice, in an interview, said that the condition of the photographer is like that of a Caspar David Friedrich figure: a lone person on the edge of the mountain…

Maybe one hundred years ago (smile, ed.). Today, wherever you go there are people. I am never alone, it is rare even when I make solitary excursions in the mountains.

What brought you to photography?

I am self-taught, I did not have any specialized training. When I was young I worked in Germany, for Siemens, in the technical division: electronics, computers, hardware. In those years I had already started to take pictures. I was very interested in experimental film, too. Unfortunately, for economic reasons I did not pursue that interest, in that period.

What period was that?

1975-77. The next year I returned to Bolzano. I worked for a software company and continued to work on photography, but without haste.

Your first photography project?

The first of any importance was a research project in Alto Adige on a silver mine, a place of historical significance during the time of the Fuggers of Augsburg, who from Germany held European power over mining. I documented the site, analyzing the social background. The images were still in black and white.

What kind of camera did you use in the beginning?

A 6×7, manual.

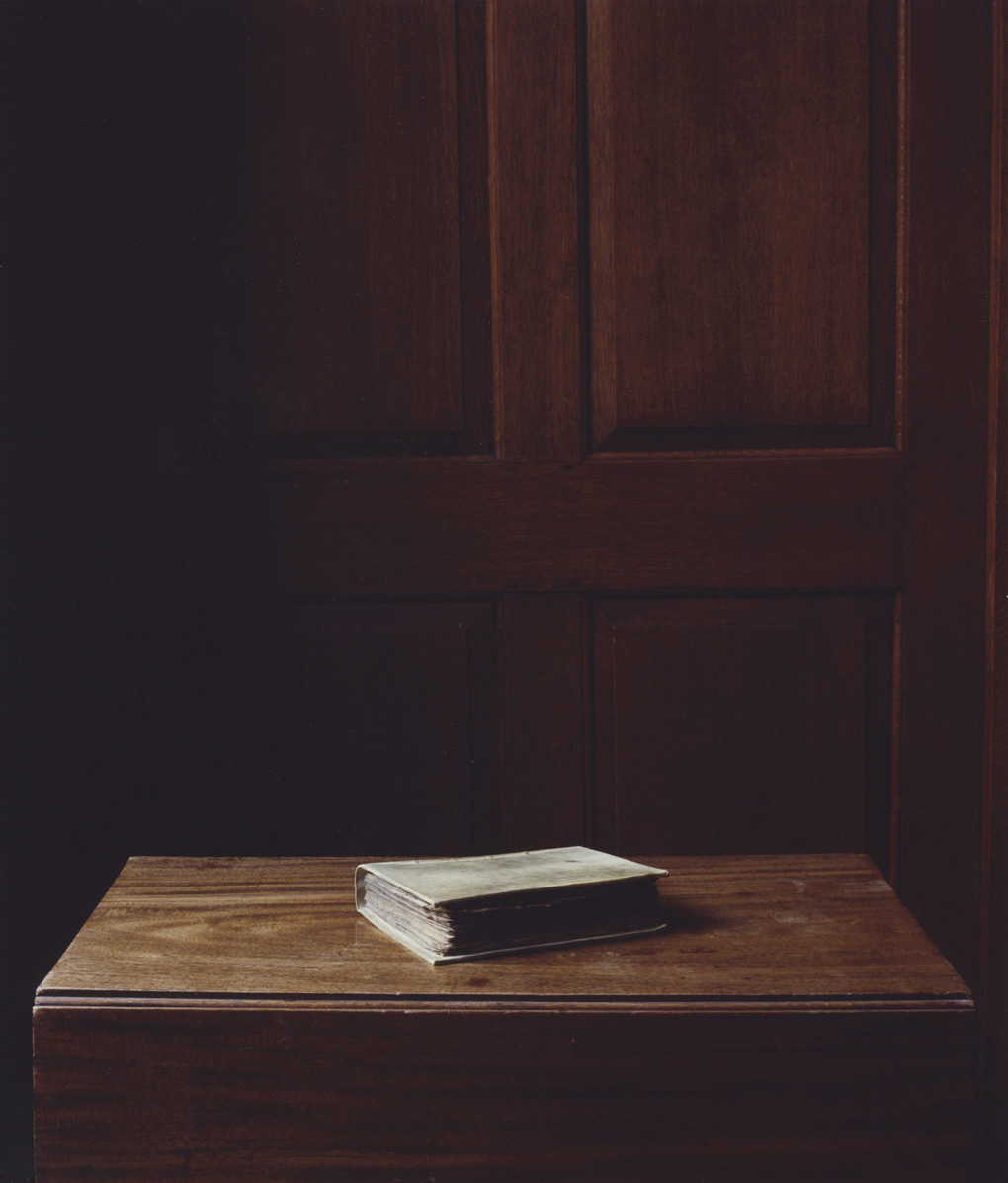

![Walter Niedermayr, Sachsenhausen, 3/2007.]()

Walter Niedermayr, Sachsenhausen, 3/2007. Courtesy: Galleria Suzy Shammah, Milano e/and Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin/Stockholm

Did you develop the film in a darkroom?

Yes, at the time. I still have a darkroom at home, but I no longer use it.

Do you miss it?

I liked it, but it was complicated. I would spend entire nights in there, developing, printing, enlarging. I did it on my own: I was fascinated, I wanted to understand how the process worked. Today I still work analog, I use film, but then we do scanning, digital processing, and then prints. Everything has changed in just a few years.

Ansel Adams, a grand old man of photography, said: “I have often thought that if photography were ‘difficult’ in the true sense of the term – meaning that the creation of a simple photograph would entail as much time and effort as the production of a good watercolor or etching – there would be a vast improvement in total output. The sheer ease with which we can produce a superficial image often leads to creative disaster.” Do you agree?

It depends on what you want to do with the photographic medium, on how you use it. Technique has never been a problem for me. I managed to learn by myself. Of course I also got to know a number of photographers. For example, one fundamental acquaintance was Lewis Baltz, one of the protagonists of the New Topographic period. His research on landscape had an influence on my work. In particular, the Park City project, done in the early eighties, near Salt Lake City, the second home of Americans: debris, buildings under construction, devastation of the territory. Years ago I went to visit that part of America, I was very curious to see what had changed. I am also fascinated by Baltz’s more recent works, his language is still very contemporary. Another photographer that interested me was Stephen Shore.

Both Baltz and Shore have worked on landscape. In much earlier times, even Vermeer used the camera obscura for many of his paintings, certainly for the Little Street in Delft, reproducing on the canvas what really appeared before his eyes. What relationship do you have with the reality you photograph?

I think the image is a thing in itself: the photograph, in the end, is a two-dimensional surface. There is a relationship between what we photograph and reality, but what the image narrates for us is another reality itself. It is a transformation of the visible. I’ve always been fascinated by the relationship between the reality of space and the reality of the image.

Germany, Italy. Technology and computers: an abstract, mathematical universe. What urged you to come to terms with the physical landscape?

To start by working on the Alpine landscape was rather obvious, given the fact that the mountains are a topography that is very close to me, and has always piqued my curiosity. As a child I often went walking on the mountains with my father, it is the landscape that surrounds me. My interest in the Alps came from the change of mission of these places. Over the years much has changed. Tourism has grown by leaps and bounds.

Framing is the simplest way to eliminate something from our retinal field of perception. With framing, one makes a window on reality. At times it is a portion motivated by a whole. What gets excluded?

I think that every image is just a fragment of something much more complex. From a scene, I try to frame what interests me: the landscape that is used by man, that is structured. The pure landscape, without human impact, doesn’t fascinate me particularly. Maybe it doesn’t even exist any longer, man has already been everywhere.

For Italian photography, the event that contributed more than others to launch a radical change was the project Viaggio in Italia (Italian Journey, ed) by Luigi Ghirri. That was in 1984. The project, an exhibition and a book, involved a group of young photographers: Gabriele Basilico, Mimmo Jodice, Guido Guidi, Mario Cresci, Roberto Salbiati, Olivo Barbieri, Vincenzo Castella and Giovanni Chiaramonte. What type of link do you have with that period?

It was undoubtedly a very important time, which may somehow have influenced me. Today, though, the way of thinking about photography has changed a bit. I think that photographing the landscape with the aim of producing a pure record no longer has the sense it once did.

If we look for the origin of this interest in landscape, important figures of reference include the Alinari brothers, Giuseppe Pagano and Paolo Monti, Mario Sironi. But also the great Americans, from Walker Evans to Lee Friedlander, Robert Frank, William Eggleston. Looking at Europe, we should mention Bernd and Hilla Becher, with their cataloguing of industrial architecture. With such a dense past, is there still a way to go beyond the “tradition”?

When I did my first series, in 1987, I wondered if it made sense to give up the work on single images, because the single image then becomes an icon. The truth is that what we see on a retinal level is never a single image, but multiple points of view. Thus the series. With this method, I have tried to go in another direction. I also believe that we include, in every shot, what we carry around inside us: culture, primal perception, everything that goes into our own story. It is only with this heavy equipment that we make our images. If we see photography in this light, every author has his own specific gaze that goes beyond schools, beyond tradition.

![Walter Niedermayr, Sachsenhausen, 23/2007.]()

Walter Niedermayr, Sachsenhausen, 23/2007. Courtesy: Galleria Suzy Shammah, Milano e/and Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin/Stockholm.

Getting beyond tradition also means considering the presence of a human landscape. Much landscape photography continues to exclude that.

A certain type of photography cultivates the obsession with clean spaces, without people. Landscape and architecture, or just space, exist with people: if there are no people, there is no space. In my works on the mountain environment, the presence of people is essential: people give an idea of the scale, they tell us where things are, the size of a surface. They are a parameter of reference.

Baudelaire said that photography is the “refuge of failed painters.” Even today, the relationship between art and photography is controversial. War reporting is often shown in exhibitions in places usually devoted to art.

I see photography as one medium that is available to art, a medium that can be art or not: it depends on what the artist or the photographer does with this medium, on the research conducted with it. The matter of who defines what is art is a different question. Personally, I don’t know if I make art, I have never said that. Of course, then there’s the market…

Photography and the contemporary…

Contemporary photography is defined on the basis of the relationship I have with the contemporary world. It is related to the way I move, the things I do. Today the relationship with the landscape, perhaps, has become more direct, immediate. There is no longer that attitude of contemplation, like Caspar David Friedrich. My interest in the photographic medium is to render visible what, in part, can go beyond normal representation. Photography cannot replace the aura of the original, so it asks itself about its role as a means of expression: it asks itself what it can point out and reveal, without claiming to represent the truth.

Among your recent works, there is also the one in which you go head-to-head with the Japanese studio SANAA, namely Kazuyo Sejima, director of the next Venice Architectural Biennial, and Ryue Nishizawa. How did you begin working together?

I met them in the eighties. They already seemed like very interesting architects back then. At the end of 1990 I received an email from their studio. They had found a book of mine in Spain and asked if we could meet in Tokyo, to show me their works of architecture. In that period I was preparing an exhibition in Japan. We met, and found that we had some common interests that were not so far apart.

What attracts you about the architecture of SANAA?

It is a very essential, apparently simple architecture, I’d say it has a complex simplicity, with a tendency to relativize the relationship between form and content, while always remaining very functional. It is never spectacular, though they work on the cutting edge of feasibility. In our case, it is a sort of ambivalence of architecture, underlined by the use of glass and transparency. In photography, I too try to defy the limit, that of the visible, of representation. This is a central aspect of my work.

Walter Benjamin said it is easier to grasp a work of architecture through the camera than in reality. What happens when architecture is seen by an artist?

SANAA have never thought of me as a documentary photographer. I am interested in conveying a subjective perception, that belongs to the image. My way of working in series is opposed to the traditional conception of static space, and perhaps it conveys the dynamic idea of the perceptive itinerary. Already, at the start, it was clear that my pictures were not documentation, but research on their architecture. The projects by SANAA that have certainly fascinated me most are the 21st Century Museum at Kanazawa, the Glass Pavilion of the Art Museum of Toledo, Ohio, and the latest project, the Rolex Center in Lausanne, Switzerland, maybe the most interesting of all. What strikes me is the experimentation with a new way of considering movement inside a space: the direct experience of the place is different from one’s perception of it. It is a bit like walking in a hilly landscape…

![Walter Niedermayr, Raumfolgen, 132/2004.]()

Walter Niedermayr, Raumfolgen, 132/2004. Courtesy: Galleria Suzy Shammah, Milano e/and Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin/Stockholm.

Ruff has investigated Mies van der Rohe for years: are there iconic works of architecture with which you would like to establish a dialogue?

I wouldn’t know. Ruff has another approach. Mies van der Rohe is part of the history of architecture, a classic. The work of SANAA is very contemporary. Sejima and Nishizawa live now and design now, in a way that is very democratic, in some aspects.

I imagine you have visited their studio in Tokyo: how did you survive the creative chaos there?

That’s Japan. For us Europeans it may seem chaotic, but you get the sensation, in any case, of a very systematic order. There are many people, working in very limited spaces. All this requires a lot of discipline and respect for others. Recently they changed their studio, but the atmosphere is the same: twenty, thirty people all working together, day and night. A flow of energies that becomes calmer in certain moments, thanks to the mitigating presence of a certain number of European assistants, who by nature have other rhythms. It is another way of thinking about the profession, Kazuyo works very hard too. For us Europeans it is a very different, almost dazing experience.

SANAA Tokyo, Niedermayr Bolzano: why have you chosen to live far away from the places that are usually indicated as the cultural centers?

I believe we all make and choose our own centers. Today, if we are interested in things, in experiences, we can easily reach them, and get information. Clearly there are places where there is more movement: Berlin, London, New York. In the end the quality of life here in Bolzano is not bad. At times, if I feel isolated, I go somewhere. I travel often. I like to stop for a while in another place, and then come back here.

For years now, art photography has always expressed itself in extralarge format, almost as if the format itself could provide the aura. What is the importance of size in contemporary photography, and specifically in your work?

Format is definitely something to decide on in a precise way, without necessarily considering the dictates of the market. At the start, I think the large format was partially motivated by the desire to escape from the photographic rectangle, a sort of shortcut to meet the art world halfway. In my research the size depends on the content of the image. I also consider the relationship with the space where the work will be shown. From this viewpoint, I may also decide to print things very small. You have to see how you want to construct your own show. Behind you there is a diptych that is part of the project on prisons: I have used that same image in a very small format, in New York, and in extralarge size in other contexts. It depends on the situation.

From format to number of prints. According to Thomas Ruff, the limited edition is handy. It is a way of considering a work complete, closed. And it helps to boost prices. What do you think?

I do editions of six. Clearly the price changes once you have made this decision. When the six copies of a work are printed, the edition is finished. Of course photography offers you the possibility of making infinite images, but a choice of that kind requires other contexts.

Market, prices, galleries. What’s the atmosphere right now?

I believe artists should be more independent, they should also do projects outside the circuits of art and art galleries. The gallery has an important role if it considers itself responsible not just for its own affairs, but also with respect to the artist, to facilitate his growth. In periods of economic difficulty like this one, the qualities of a gallerist become more evident. Maybe I’ve been lucky, because I entered the circuit years ago. Today I hear about other artists who have problems with galleries, which are tending to vanish, in this period, or to invest less.

You have galleries in New York, Milan, Stockholm and Berlin.

As I said, I’m not complaining.

How do you work on an exhibition?

I always start with the space, a floor plan, and then I start to think about what can be done there. In the past I experimented with the use of renderings. I tried it, but I discovered it doesn’t work very well, so in the end I changed everything. All I need is paper, I can imagine things that way. For now I have always shown new works, for the most part. I haven’t done any retrospectives yet. Every thematic exhibition requires about six months of work. Though in the end, I must admit that to finish a work I need to feel a certain amount of pressure…

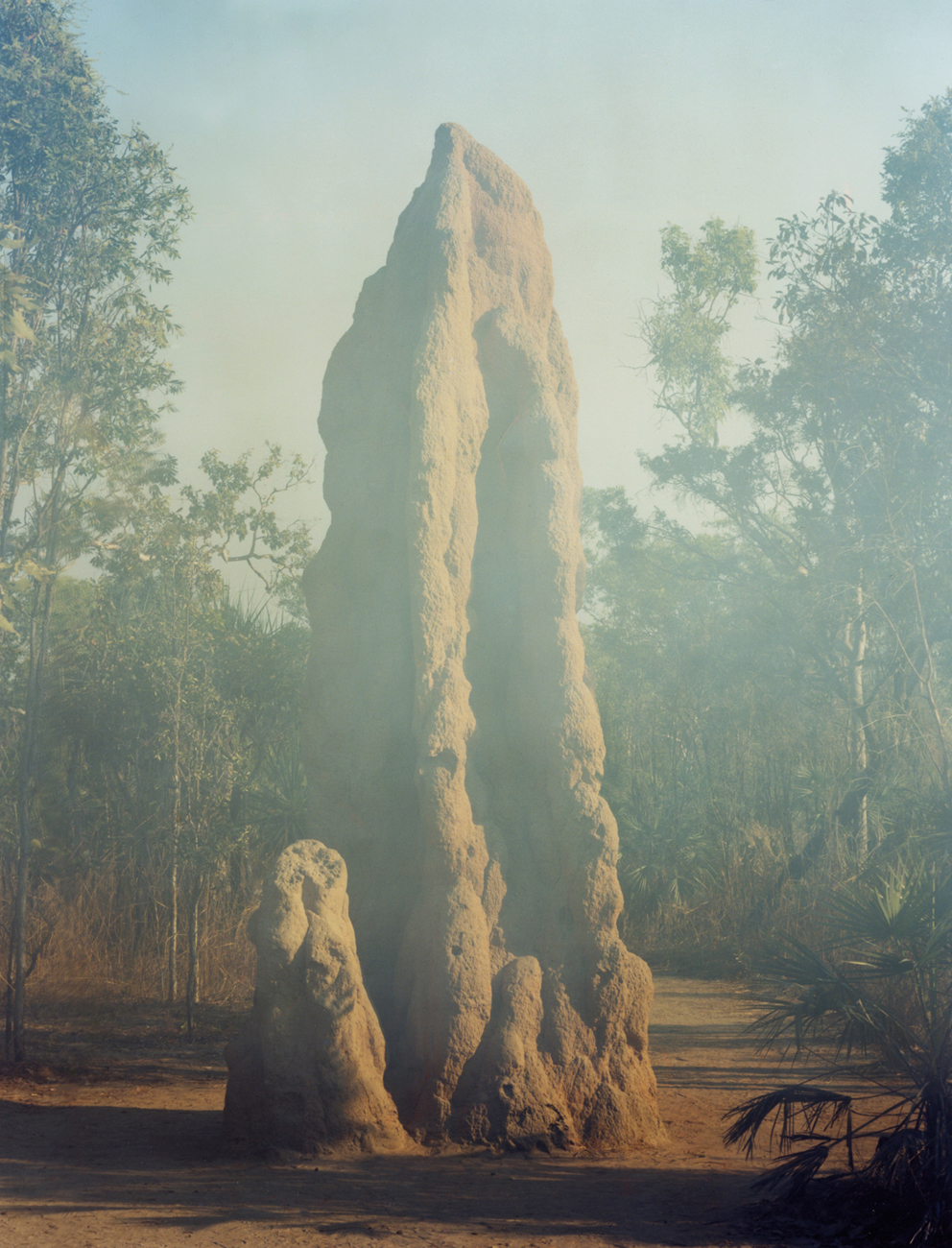

![Walter Niedermayr, Bildraum S, 164/2007.]()

Walter Niedermayr, Bildraum S, 164/2007. Courtesy: Galleria Suzy Shammah, Milano e/and Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin/Stockholm.

Let’s talk about books.

With respect to an exhibition, a book is something else. Another perception. Books interest me very much. I try to work with graphic designers who understand my way of working. Often it is very hard to comprehend each other: at times I have the impression that lettering does not establish a harmonious dialogue with the images. For Walter Niedermayr/SANAA I worked with a Dutch graphic designer: at the start we argued often, there were misunderstandings. It was a rather demanding process: but in the end a very beautiful book emerged.

How do you do your editing?

First I try to organize a nucleus of images, then I try to put them in a sequence. I take them home, I put them on the floor, I move them around until I see that the thing might work. Then the graphic designer arrives and wants to change things. It is a continuing process of changes, a give and take of ideas.

How do you defend yourself against the hyperproduction of images that surrounds us?

I concentrate on my images, on my way of seeing them. To defend yourself you also have to be very rigorous about the choice of images, and not produce them endlessly. Also by making fewer books. The multiplication of images through books leads to a sort of inflation. Another possibility might be that of being very radical. Perhaps it is enough to constantly question the meaning of your work.

How many books have you published?

In twenty years I have done nine monographs.

One of the recent books is Station Z: Memorial Sachsenhausen, Walter Niedermayr/HG Merz.

Station Z is the name of the cremation oven of the concentration camp of Sachsenhausen, one of the first Nazi camps. From 1936 to 1945 more than two hundred thousand people of about forty different nationalities were imprisoned at Sachsenhausen. Years ago, the German architect HG Merz designed a memorial: an abstract structure, almost a sheet that protects the traces of the place. When I was asked to work on this, for me it was important to understand what would be the right time of year. I was there in January, it was quite cold, and there was a certain light, a certain atmosphere that made it possible to do the work. Before beginning to take pictures, I visited the place twice, for a better understanding of its history, the context, why this zone was selected, just thirty five kilometers north of Berlin.

Don’t you think that to represent a place like this – so laden with weighty emotional and historical character – through an aesthetically complex and refined image, might generate a short circuit?

The same question is raised by research projects like the one on the prisons. There are places where it is very difficult to stay, for me. After three days at Sachsenhausen I had the sensation that the place was expressing what had happened there. Though you can no longer see the traces, it is impossible not to feel them, they are in the air. Every step you take, you cannot avoid them.

What is your relationship with color? Over the years your works have become more and more desaturated.

The discussion on color is infinite. When I started taking photographs, and was using black and white, I already had the impression that the world of photography might be too full of contrasts. After having discovered the work of Timothy O’Sullivan, which struck me because of its soft black and white, the desaturation of color seemed more natural, closer to what we perceive. Now I realize that I often go beyond that, pushing the limit. It is as if I were seeking an increasingly big distance from the rather dated concept of saturation, which if you think about it is dictated by what the industry tells us: this would be right, it will sell better. I love neutral colors, I like a white that is more cool than warm. Working on mountain landscapes I often have white: precise, clean, it balances all the other colors.

With today’s digital technology, Photoshop and plotters, the eye is accustomed to imagining/seeing results that take concrete form in images after at least three passages. This also happens in publishing: first there is the computer monitor that shows us the image in one way, then there are the proofs, then the printing on paper. With all these passages the eye has become used to dealing with three “deceptions.” What does Niedermayr see and imagine when he looks at the world through a lens?

I believe that already back in the darkroom there were many possibilities for manipulation. Today, with digital photography, these possibilities have simply been multiplied. You can do anything. Then you have to decide what you want to do. For me it doesn’t change that much. It changes, in the sense that I no longer have to use the chemicals that were needed for developing. The same is true of color: yesterday you could filter it by analog means, today there is Photoshop, which has very great potential.

What are you working on now?

I am preparing a publication with the works I did in Iran. I’ve been there three times: 2005, 2006, 2008. I photographed the landscape of the historical and the modern city. Not just in Tehran, but also in other centers: Isfahan, Shiraz, Yazd and other places.

Is this the first time you have worked on such a faraway landscape?

Not really, I also worked in America, Japan, New Zealand. The project in Iran was organized by an institute in Vienna that focuses on cultural exchanges with Iran. Artists, architects and writers are involved, who present their research, conduct workshops and can work for up to four weeks in that country, which is a very beautiful, very interesting place. What we hear about Iran is very distorted by politics. Politics in Iran is one thing, the population is another. Most of the generation of people in their thirties would like to leave or change the system. It is a difficult, complex reality.

What kind of book will we see?

The research had to do with the new that inserts itself into tradition. I was very interested in this ambivalence: on the one hand, a very long history, three thousand years and more, spanning different periods, eras and cultures, also in architectural terms. A very lofty tradition, extremely fascinating. Think, for example, about the Iranian wind towers, simple structures but also very sophisticated in bioclimatic terms. After the Islamic revolution, the recent past has introduced an idea of architecture that has produced landscapes with no connection to history. This contrast struck me. It is as if the excluding effort of the regime had imposed an abandoning of tradition, unintentionally forcing people to look to the West for other models.

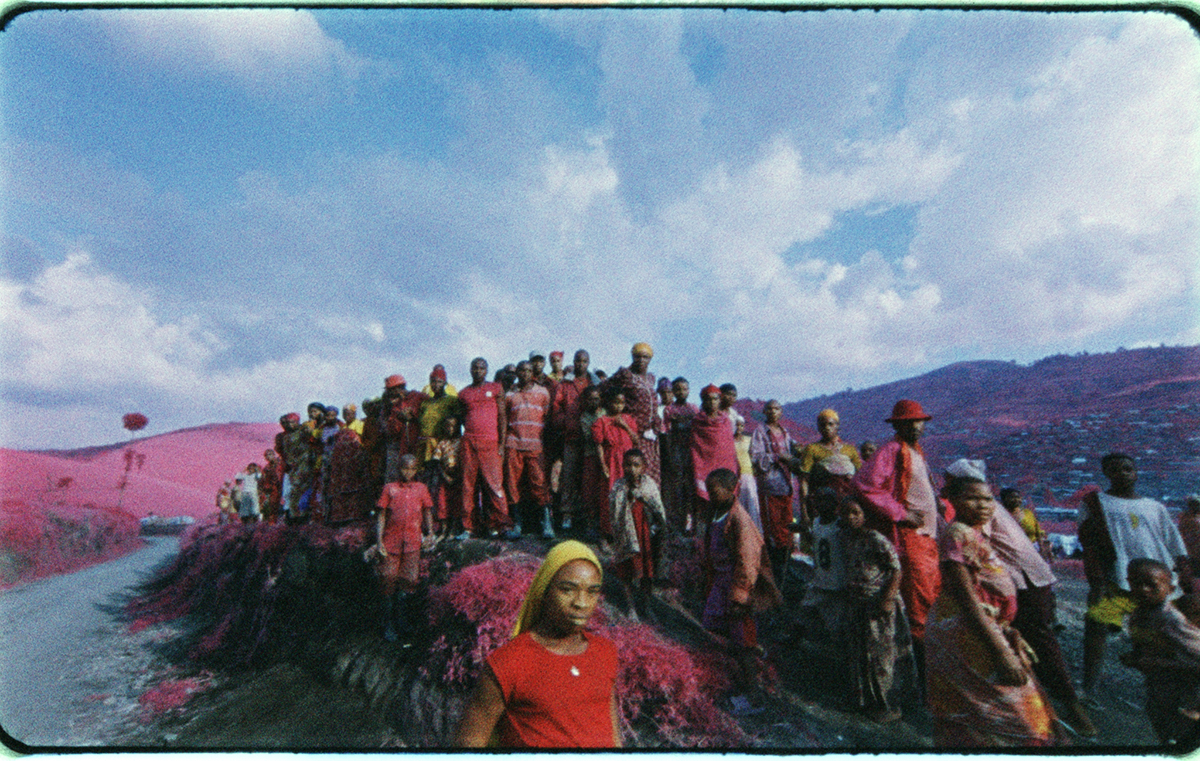

![Walter Niedermayr, Iran, 155/2008.]()

Walter Niedermayr, Iran, 155/2008. Courtesy: Galleria Suzy Shammah, Milano e/and Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin/Stockholm.

Would you show us something?

Niedermayr opens a book with Arabic characters. He turns the pages and shows us the research by about ten different authors. We see Tehran, earth constructions, monumental Iran, crumbling neighborhoods, faded suburbs. Then the surprise: the optical white of a ski resort. And, once again, everything makes sense.