(english text below)

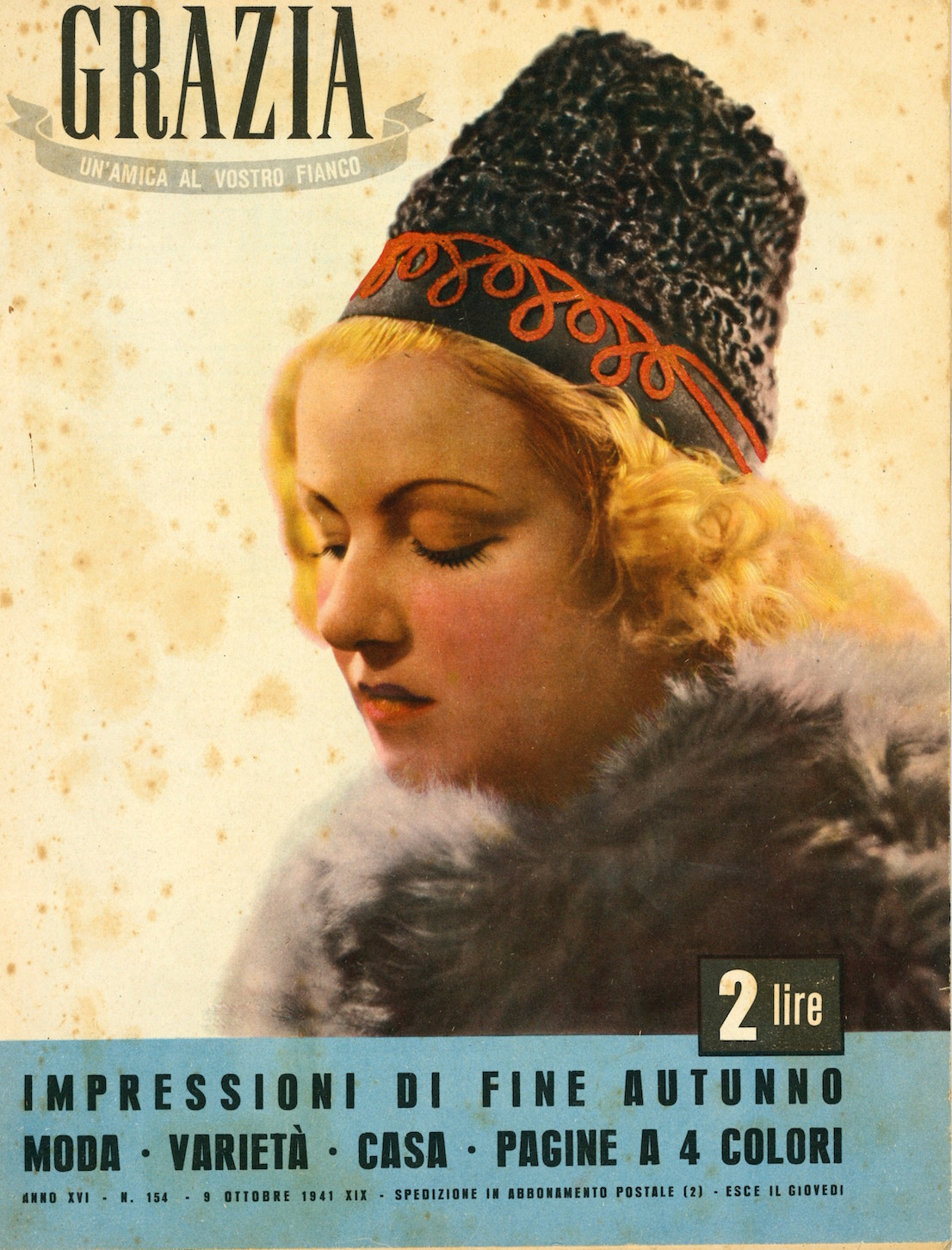

Intervista di / Interview by Federico Florian

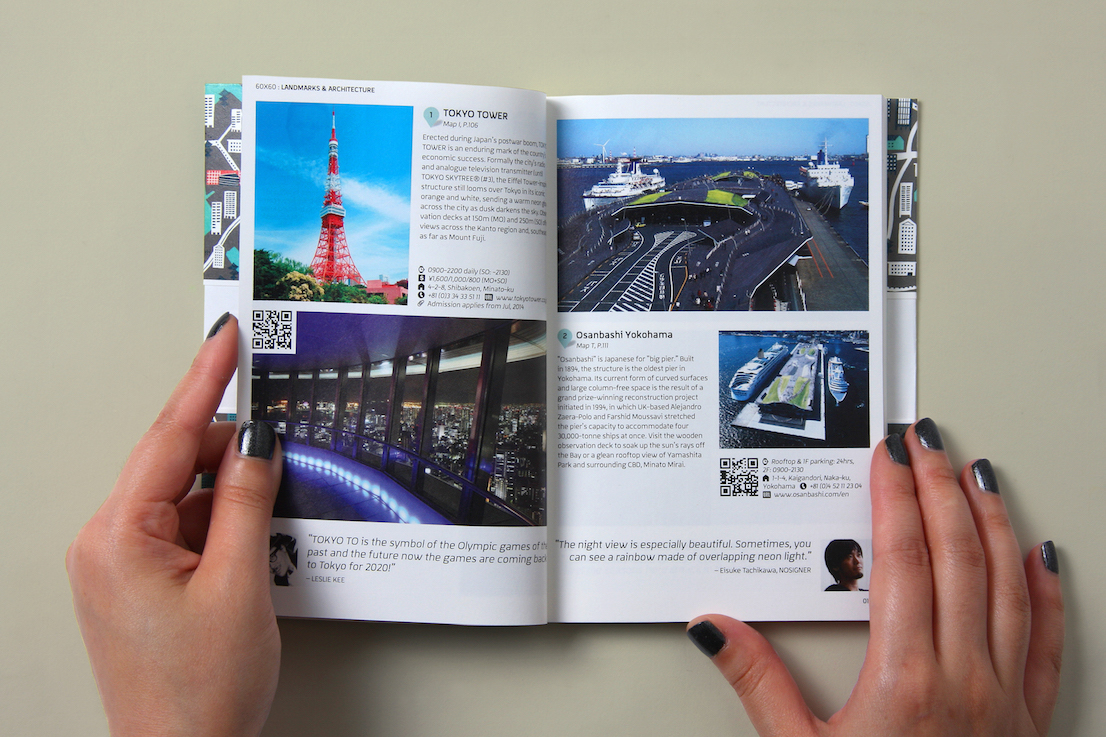

Valerio Rocco Orlando, artista milanese, classe 1978, esplora con sorprendente delicatezza il paesaggio dell’incontro e della relazione con l’Altro. Il video è il suo medium favorito: la sua macchina da presa penetra, attraverso inquadrature ravvicinatissime, nelle profondità degli sguardi e nelle pieghe dei volti dei personaggi che ritrae. La pratica di Orlando – una contemporanea forma di maieutica socratica – si fonda sul dialogo, sul confronto intimo con l’interlocutore. Dopo aver studiato drammaturgia a Milano e regia a Londra, ha vissuto a Roma, New York, Cuba, Bangalore, Tel Aviv e Seul, spostandosi di residenza in residenza e facendo del viaggio la condizione indispensabile della propria ricerca. Ho incontrato Valerio qualche mese fa a Milano, poco dopo il suo ritorno da Israele, il luogo dove girerà il suo prossimo film.

Interfaith Diaries è il titolo del progetto cui ti sei dedicato nel corso della tua residenza ad Artport Tel Aviv, a partire da maggio 2014. A causa del conflitto scoppiato a luglio dello stesso anno nella Striscia di Gaza, sei stato costretto a lasciare Israele e a interrompere il lavoro. Mi racconti di più di questa esperienza?

Interfaith Diaries è un progetto cui pensavo da molto tempo. Ho una formazione cattolica, ho trentasei anni e in questa fase della vita sto rimettendo totalmente in discussione il mio rapporto con Dio. Ci sono momenti in cui penso sia fondamentale porsi delle domande in tal senso. Da diverso tempo scrivo un diario, uno strumento che mi consente di approfondire la mia dimensione interiore. Prima dell’invito di Vardit Gross, direttrice di Artport, non ero mai stato in Israele. L’ho pensato subito come un’opportunità per produrre un nuovo lavoro proprio sul tema della spiritualità. Dunque, sono partito con le migliori intenzioni. Inizialmente, credevo che Gerusalemme potesse accogliere al meglio questa ricerca. In realtà, non è così. Lo stato israeliano è molto giovane, il progresso sociale davvero accelerato, e il rapporto delle persone con la religione è piuttosto controverso. Io poi non desideravo esplorare la realtà delle comunità ortodosse. Al contrario, quello che mi premeva approfondire era la quotidianità della gente comune e il modo in cui si relaziona alla propria dimensione spirituale.

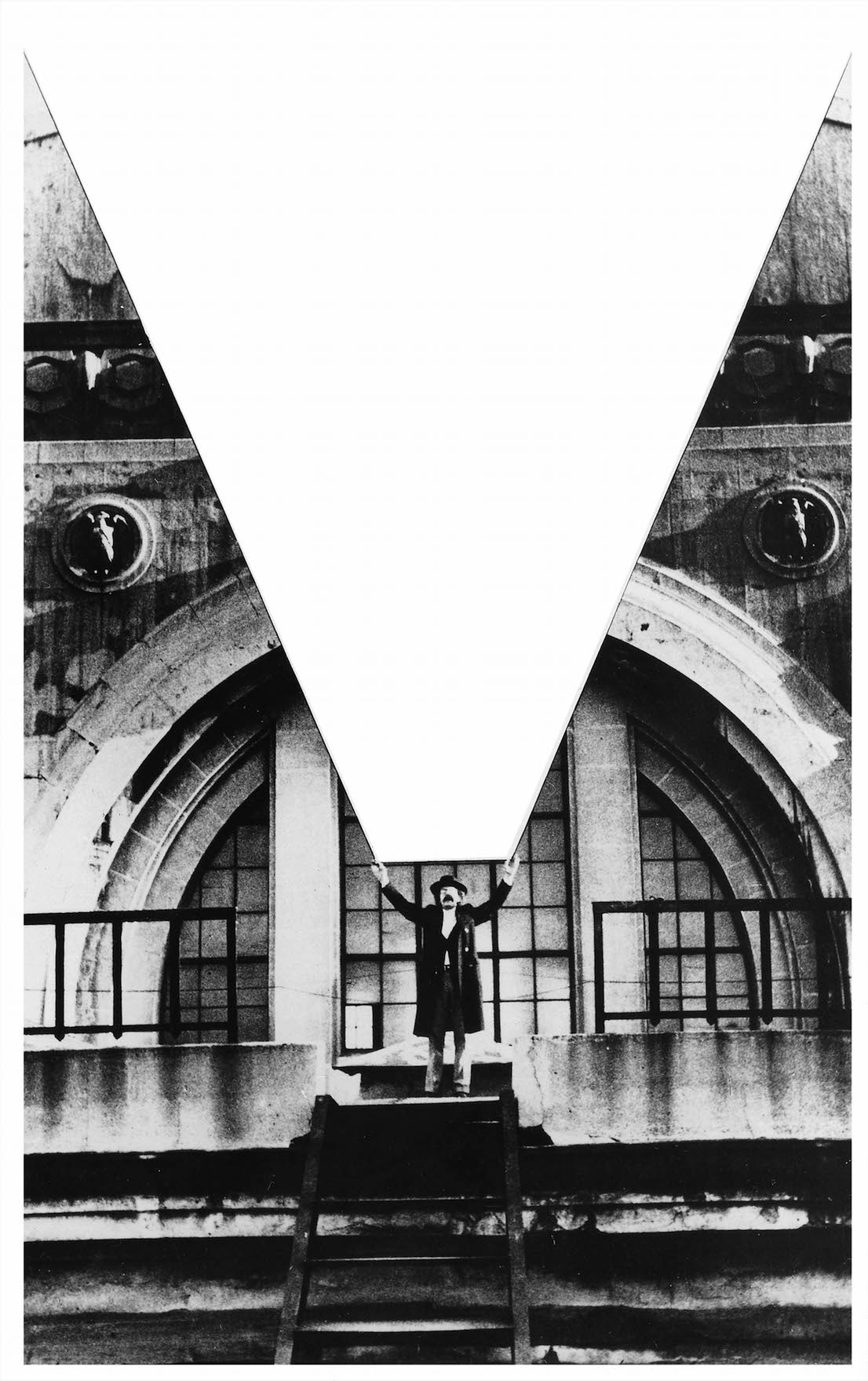

![Valerio Rocco Orlando, Interfaith Diaries, 2014.]()

Valerio Rocco Orlando, Interfaith Diaries, 2014.

Dunque, persone che si stessero ponendo i tuoi stessi interrogativi, che rispecchiassero la tua esperienza personale.

Esattamente. Individui in qualche modo vicini a me. Anche se il mio lavoro mi porta in luoghi lontani – in Corea, in Islanda, negli Stati Uniti, a Cuba, in India o, come in questo caso, in Israele – cerco sempre di raccogliere e raccontare storie che siano affini al mio vissuto. Sin dal mio arrivo in Medio Oriente, ho spiegato a tutti che non era mia intenzione raccontare il conflitto o la realtà delle minoranze religiose; volevo piuttosto interagire con chi come me stesse mettendo profondamente in discussione la propria relazione con la dimensione spirituale. A Tel Aviv, all’inizio di giugno dello scorso anno, quando ho presentato il progetto, ho esordito dicendo: “I’m looking for someone who is in some sort of spiritual journey” [Sono alla ricerca di persone che stiano intraprendendo un viaggio in qualche modo trascendentale]. Questa open call includeva molte possibilità: non proponevo la ricerca di una tipologia specifica di individuo. Mi sono aperto a narrazioni diverse e ho cominciato a frequentare realtà alternative. Tra tutte, una sinagoga un po’ speciale, il cui rabbino accoglie chi non si riconosce più nella propria comunità d’origine per una serie di scelte personali. Ad esempio, coppie di donne omosessuali con bambini: storie distanti dalla famiglia ortodossa classica. Per raccontarti un aneddoto, tra queste persone ho conosciuto un ragazzo di ventotto anni che ha deciso di partecipare al progetto e condividere così la propria esperienza. Yarden è originario di un kibbutz vicino a Tel Aviv, dove anni fa si è sposato e ha avuto un bambino. A un certo punto della sua vita ha riconosciuto e accettato la propria omosessualità, decidendo di lasciare la famiglia per trasferirsi in città. Ora vive con un compagno a Tel Aviv e frequenta la sinagoga di cui ti ho appena parlato. Yarden mi raccontava che da ragazzo era solito camminare nei campi vicino a casa, di notte, e pregare. Una cosa che non può più fare e per cui prova una certa nostalgia. Quando gli ho chiesto, per questo nuovo film, di pensare a un luogo che rappresentasse il suo percorso interiore, mi ha parlato di queste passeggiate. L’idea è di girare una camminata notturna in uno di quei terreni – un lungo piano sequenza in cui lui porta per mano suo figlio. Una scelta nata da un dialogo costante e da una fiducia reciproca. Non ti nascondo l’entusiasmo di questo incontro. Ad ogni modo, non siamo ancora riusciti a girare questa scena perché, nel momento in cui è scoppiata la guerra, Yarden è stato chiamato come riserva ed è partito per Gaza.

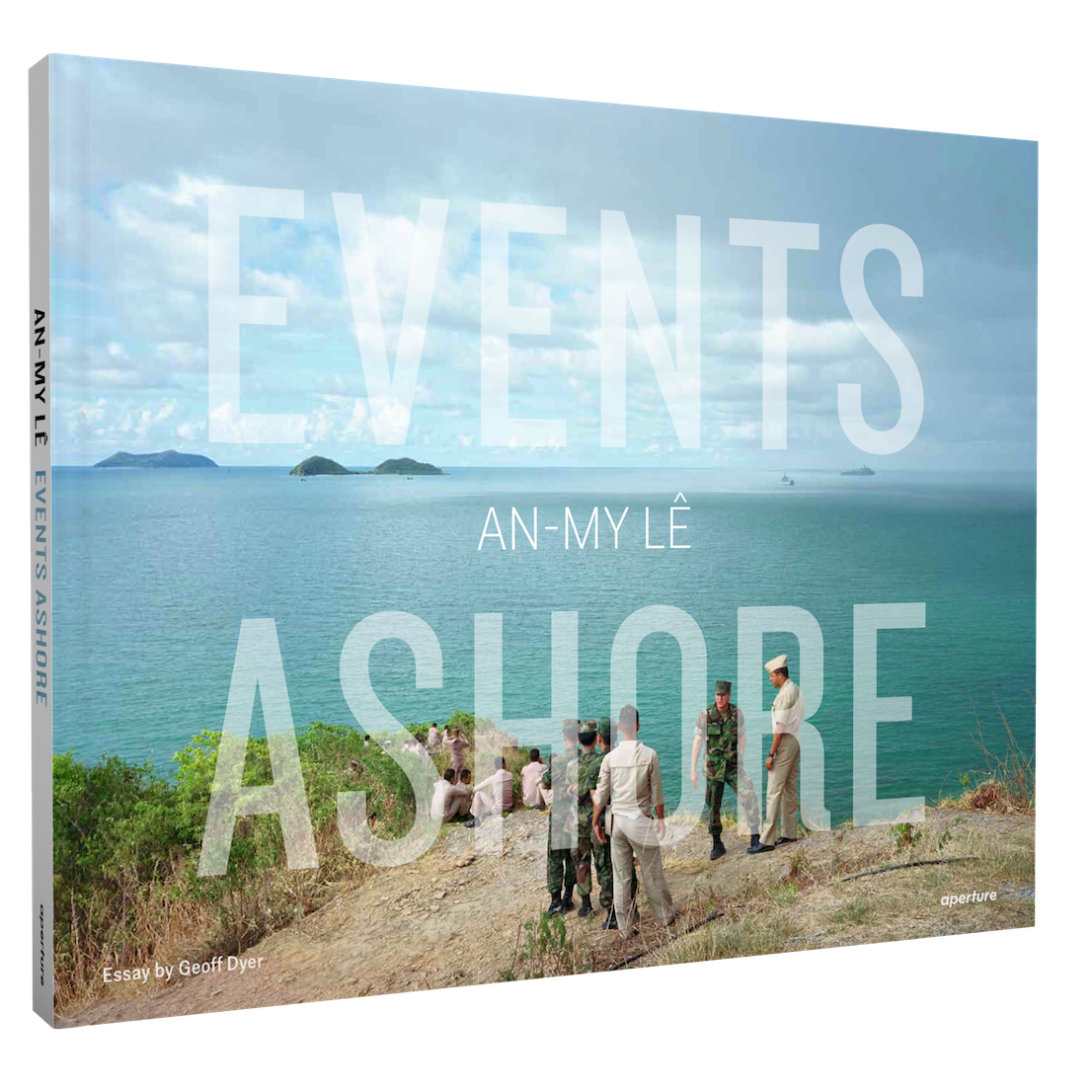

![Valerio Rocco Orlando, Eva, 2010. ISCP, New York.]()

Valerio Rocco Orlando, Eva, 2010. ISCP, New York.

Come è stato vivere in Israele in pieno conflitto, anche se per un breve periodo?

Non ho mai temuto per la mia sicurezza. Tuttavia, la quotidianità era completamente sottosopra, sebbene a Tel Aviv nessuno sia rimasto ferito. Quei due mesi sono stati per me un periodo di preparazione e ricerca. Sapevo che non avrei effettivamente girato o realizzato concretamente il progetto. Piuttosto, cercavo di comprendere come svilupparlo. Per la prima volta dopo dieci anni ho deciso di confrontarmi con un attore, scegliendo di collaborare con Saleh Bakri, nato in Palestina, con cittadinanza israeliana, uno dei firmatari del manifesto del BDS, movimento fondato da alcuni intellettuali palestinesi che boicottano Israele rifiutandosi di partecipare a produzioni governative. È stato molto difficile entrare in contatto con Saleh e cominciare a lavorare con lui: i fondi della mia residenza, infatti, provengono da una fondazione americana. Dopo una lunga serie di email, telefonate e tentativi di avvicinamento fallimentari, un giorno, finalmente, Saleh ha accettato di vedermi. Mi ha invitato a casa sua, ad Haifa, una città a nord del paese, vicino al Libano. La guerra era già cominciata e il viaggio è stato piuttosto complicato. Ricordo la vista meravigliosa sul porto dal suo terrazzo. Lì cominciai a esporre le mie idee, parlando in modo concitato, nella speranza di riuscire in poco tempo a incuriosirlo e persuaderlo a partecipare. Dopo avermi ascoltato senza intervenire, mi offrì un espresso dicendo: “Valerio, my friend, relax!”. Allora capii che non c’era bisogno di convincerlo. Si era documentato su di me e aveva già deciso di prendere parte al progetto. Quel giorno decidemmo di scrivere insieme il lavoro. Gli chiesi non tanto di recitare un ruolo o un personaggio, quanto di interpretare se stesso, invitandolo a farmi da guida, un po’ come ha fatto Virgilio per Dante. Doveva aiutarmi a incontrare le persone, israeliani e palestinesi, instaurando un dialogo con i partecipanti. Abbiamo iniziato a definire insieme il testo, fino a che mi sono reso conto che era impossibile andare avanti e perciò, a malincuore, ho deciso di rimandare le riprese. Non solo per le ovvie difficoltà sul piano emotivo e relazionale. Molti dei luoghi che dovevamo percorrere erano troppo vicini al conflitto. Ti parlo, per esempio, del deserto del Negev, poco distante da Gaza, dove mi sarebbe piaciuto girare una scena centrale del film. Avevo preso una macchina a noleggio, e guidando sulla strada abbiamo incrociato una serie di carri armati che venivano trasportati per preparare l’attacco di terra. Dormendo nel deserto, sentivamo il rumore delle bombe. Il progetto è stato interrotto e il budget di produzione congelato. Per ora lavoriamo a distanza. La mia intenzione è di tornare sul posto l’anno prossimo (nel 2015, nda) per riprendere tutti i contatti e per proseguire il lavoro.

Quale forma assumerà il lavoro finale? Sarà una videoinstallazione?

Interfaith Diaries sarà un lavoro diverso dagli altri. Come ti dicevo, innanzitutto lavorerò con un attore – e sono certo che Saleh Bakri sia la scelta giusta. È molto amato dalla gente del luogo, un attivista lucido e consapevole, una persona capace di ascoltare. Si tratterà di un film, un lungometraggio, adatto a essere mostrato sia in un museo sia in un festival o in un cinema. Non ci saranno grandi dialoghi, immagino scene con lunghe camminate. Credo che la ricerca spirituale alla base di questo lavoro, nella sua forma finale, emergerà soprattutto dal silenzio. Vedo quest’opera come una sorta di pellegrinaggio personale, in cui vengo accompagnato da individui con cui condivido un certo sentire e lo stesso atteggiamento di analisi interiore.

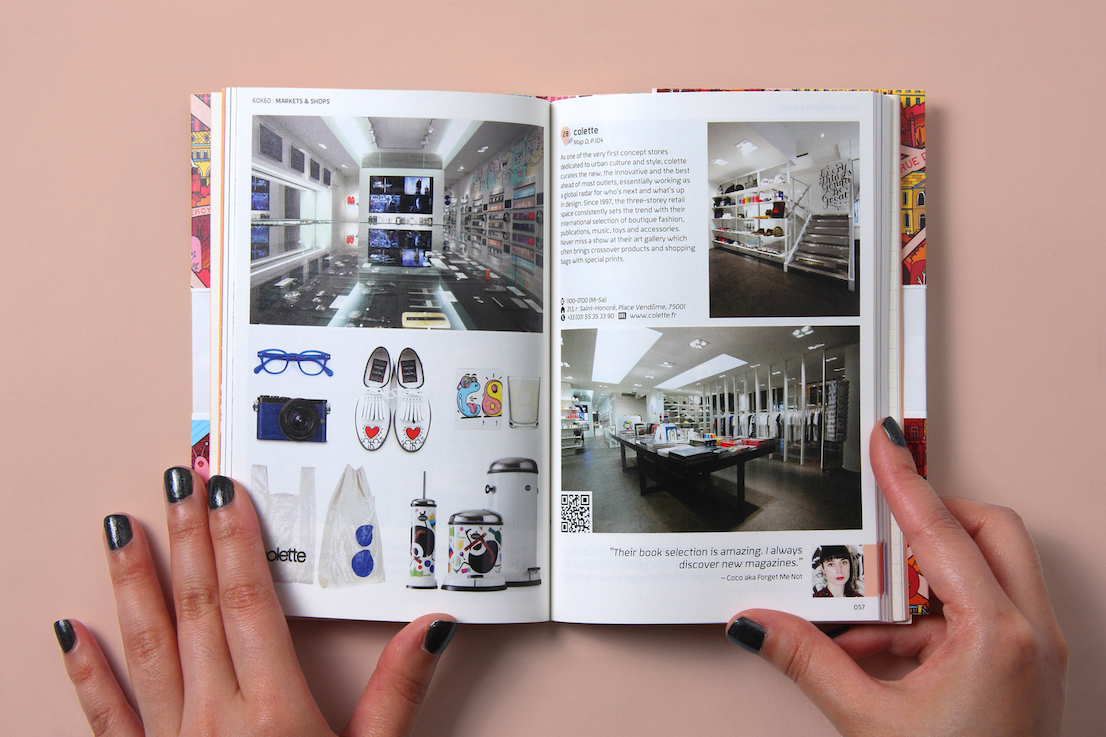

Hai studiato a Milano e a Londra. La regia è al centro del tuo lavoro. Nei tuoi video, collezioni una serie di storie e dirigi i contributi dei soggetti che interpelli nelle tue “inchieste”, ciascuna legata a un tema specifico: l’amore, l’educazione, la religione. Il risultato finale è un’equilibrata orchestrazione di volti e primissimi piani. Penso in particolare a The Sentimental Glance (2002-2007), una delle tue prime videoinstallazioni, composta dai ritratti in movimento di sei giovani donne legate al tuo vissuto personale.

Del cinema e del teatro mi hanno sempre affascinato le possibilità espressive del volto umano. Il ritratto, perciò, è sempre stato in un certo senso il mio principale campo di ricerca. Il viso fornisce un’opportunità di dialogo e di confronto. Tutti i miei video sono come degli autoritratti, anche se non compaio mai in scena e non si sente mai la mia voce. Tuttavia, la mia presenza è tangibile. Forse, l’impianto registico di tutti questi lavori – e non parlo solo dei video, ma anche dei libri, delle fotografie e delle mie installazioni – sta nell’empatia che si crea tra me e il soggetto. Per me, l’arte costituisce un percorso di conoscenza condivisa, un processo di formazione. In questo senso, l’empatia è uno straordinario veicolo di apprendimento.

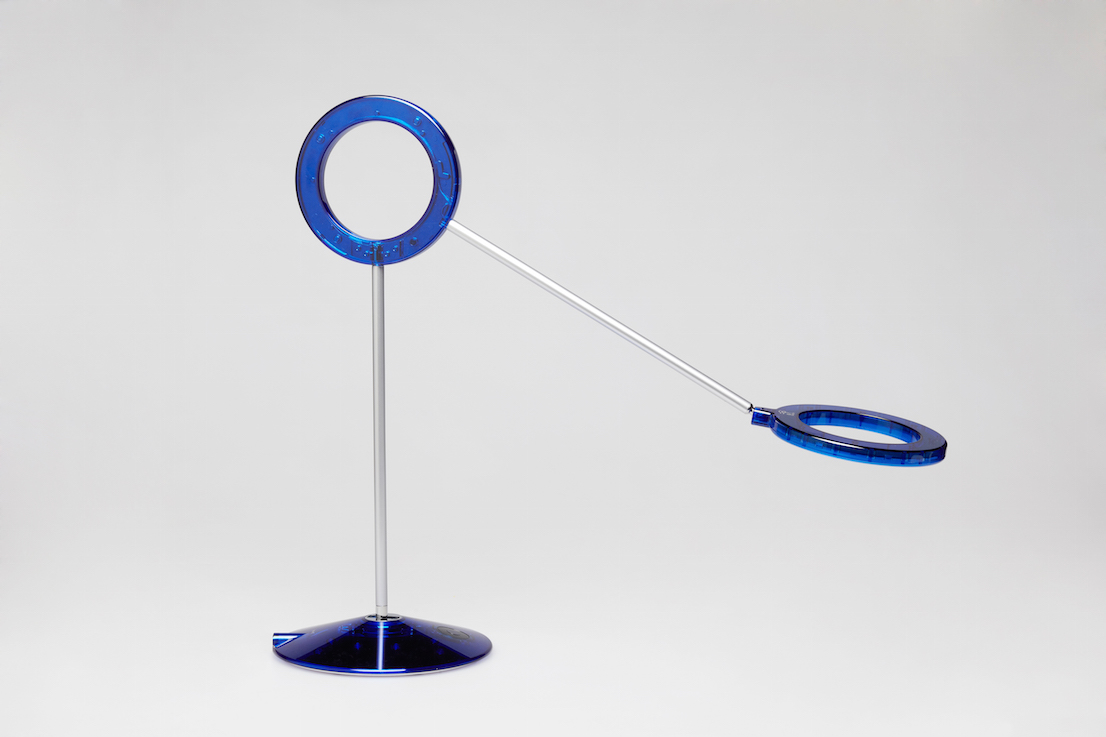

![Valerio Rocco Orlando, The Sentimental Glance, 2007.]()

Valerio Rocco Orlando, The Sentimental Glance, 2007.

Il montaggio, nei tuoi video, ricopre un ruolo fondamentale: attraverso la selezione e l’assemblaggio delle testimonianze degli individui con cui ti relazioni, l’opera si carica di un valore simbolico, sentimentale. Il che rende i tuoi lavori distanti anni luce dalla pura inchiesta sociologica.

Io non realizzo documentari: la mia ricerca è assolutamente poco scientifica. Parto in maniera emotiva e istintiva da un’esigenza di approfondimento personale; sono poi gli incontri con le persone che interpello a indicarmi la strada da seguire. Io pongo delle domande e metto in relazione le risposte: la mia idea di arte è una proposta che resta aperta. Il montaggio è il mezzo attraverso cui, in quanto artista, compio delle scelte; una di queste può essere quella di legare una storia a un’altra realizzando, per esempio, un campo-controcampo che nella realtà non è mai avvenuto. Così emerge la mia soggettività. Il cuore della regia avviene in fase di montaggio, tanto che nessun altro eccetto me può montare i miei lavori. Si tratta di un’assunzione di responsabilità, in un certo senso.

E che ruolo riveste lo spettatore nel tuo lavoro?

Un ruolo fondamentale. Il mio obiettivo è che gli interrogativi che pongo coinvolgano e stimolino lo spettatore, di modo che quest’ultimo possa entrare a far parte di quella piattaforma di riflessione, dialogo e confronto che è alla base della mia opera.

Citi spesso Jean-Luc Nancy e la sua nozione di “essere singolare-plurale”, ovvero l’idea per cui l’essenza della nostra esistenza sia la “co-esistenza”, il vivere insieme agli altri. Nei tuoi lavori esplori il concetto di identità e cerchi di comprendere fino a che punto l’individuo venga influenzato dal senso di appartenenza a una comunità più o meno piccola, come le coppie di innamorati in Lover’s Discourse (2010), gli studenti di What Education for Mars? (2011-2013) o gli artisti in residenza di The Reverse Grand Tour (2012).

Prima di tutto, non m’interessa lavorare con comunità enormi poiché quello che devo preservare – e sono fermamente convinto di ciò – è il rapporto personale uno a uno. Per me, il concetto di identità è fortemente in relazione con quello di comunità, e penso che l’arte e gli artisti abbiano grandi possibilità di azione su questo piano. L’intimità diviene la chiave di accesso alla verità.

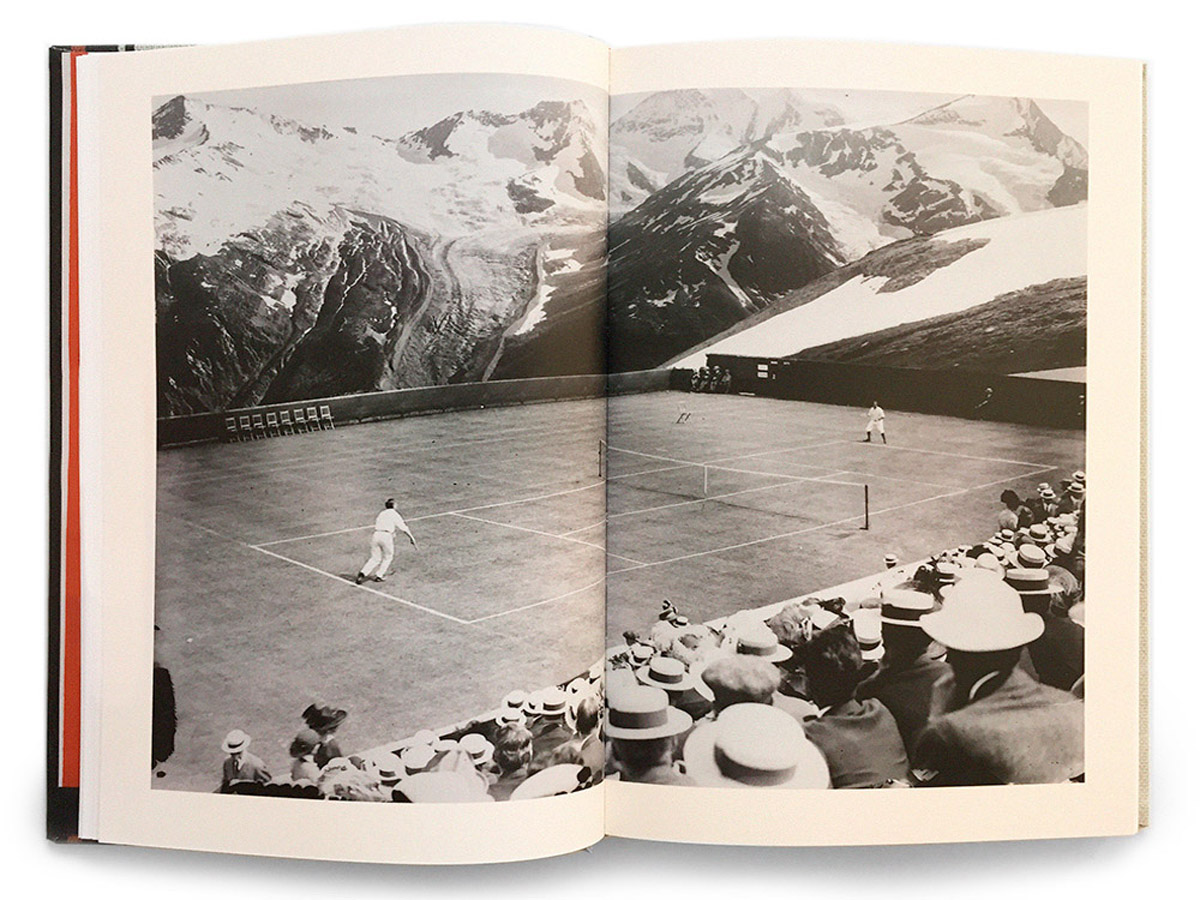

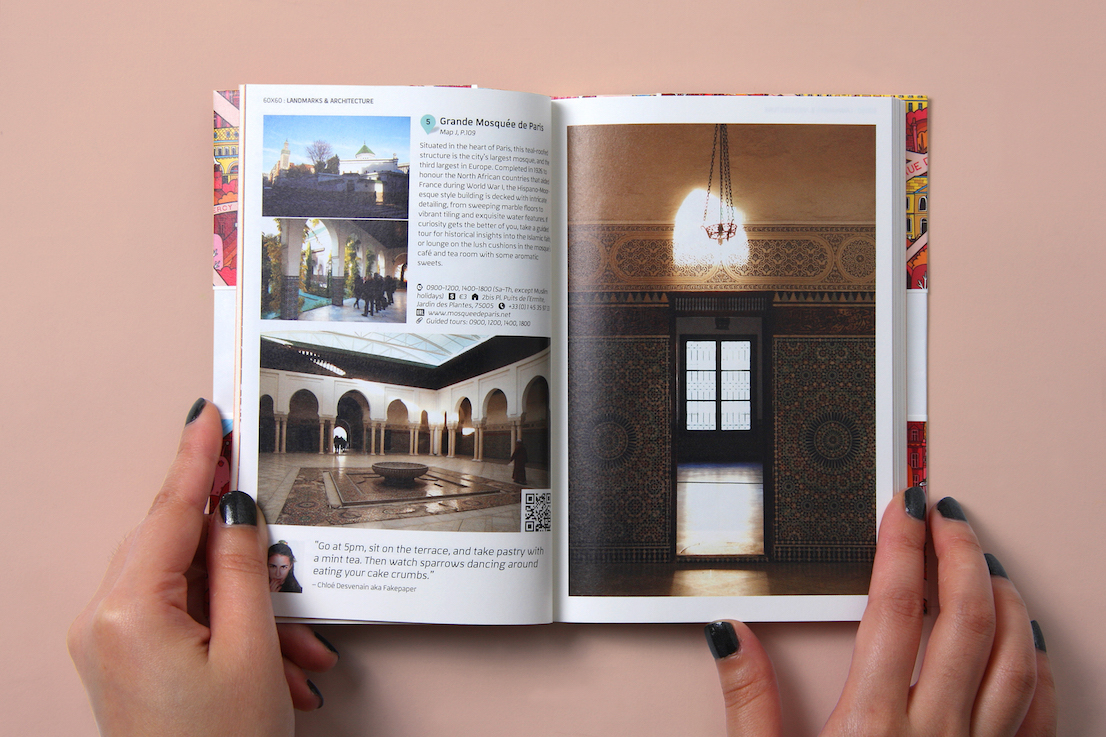

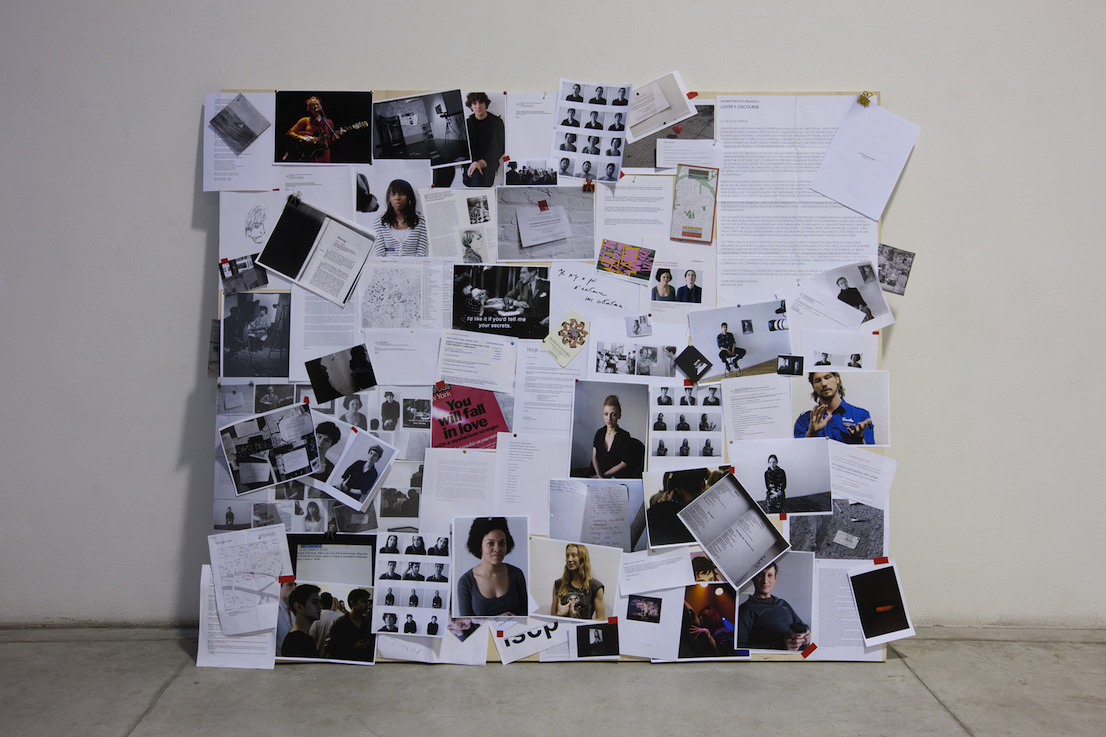

![Valerio Rocco Orlando, WHAT EDUCATION FOR MARS?, 2011-2013]()

Valerio Rocco Orlando, What Education for Mars?, 2011-2013.

Potremmo dire che le relazioni che instauri con le persone per realizzare i tuoi lavori contribuiscono alla definizione della tua identità.

Sì, di individuo e di artista. Questo avviene a partire da The Sentimental Glance, che è un grande affresco della mia formazione, un autoritratto attraverso i volti di alcune giovani donne che ho conosciuto nell’arco di alcuni anni. Si tratta di una produzione diversa rispetto alle ultime, in cui mi confronto con comunità lontane ed esotiche – basti pensare alla foresta indiana dove ho lavorato la scorsa estate con gli studenti della Valley School. Tuttavia, non riscontro grandi differenze rispetto alla metodologia degli altri lavori. In tutti quanti è forte il carattere personale, per me sono un’unica grande opera. Tanto che sogno di mostrare un giorno tutti questi video e film insieme: vorrei che lo spettatore entrasse in questo labirinto di storie: alcune sussurrate, altre parlate, mai urlate, dal carattere intimo, e allo stesso tempo sociale. Mi piace l’idea di coinvolgere il pubblico in un grande dialogo, in parte autobiografico, ma che di fatto racconta la vita degli altri.

Vedo il tuo lavoro come una forma di maieutica socratica: il dialogo, su cui si fonda la tua pratica, diviene strumento di crescita e conoscenza.

È proprio così. Il dialogo è un mezzo per guardarsi negli occhi, ascoltarsi ed entrare in profondità, in contatto con l’altro. Martin Buber parla di “sphere of the between”, dello spazio che si crea tra due persone nell’atto dell’incontro. Egli sostiene che quando due uomini si ritrovano faccia a faccia accade qualcosa di unico, che contribuisce a rimodellare l’identità dell’individuo. Io sono convinto di questo: tramite il confronto profondo con l’altro rimettiamo continuamente in discussione noi stessi; senza di esso, sarei come un pittore senza musa, tela e colori.

Per tornare al ruolo principale che il volto umano assume nei tuoi video, in più di un’occasione hai paragonato i visi ripresi dalla tua macchina da presa a dei paesaggi. Giuliana Bruno, con il suo Atlante delle emozioni, costituisce uno dei tuoi riferimenti letterari. Mi affascina molto la connessione tra corpo e paesaggio, anatomia e geografia, su cui pare basarsi il tuo linguaggio formale.

Ho sempre concepito il volto in rapporto con lo spazio. Nel momento in cui mi confronto con l’altro, il viso diventa un tessuto organico capace di registrare uno spettro di emozioni: in questo senso diviene paesaggio. Desidero che i miei video vengano mostrati su grandi schermi o attraverso proiezioni su larga scala non per una semplice ragione formale, ma perché il volto, attraverso il close-up, l’inquadratura ravvicinatissima sullo sguardo, diviene un luogo all’interno del quale lo spettatore può perdersi. Tali requisiti favoriscono una sorta di immersione emozionale, dal carattere catartico. Fin da piccolo, al cinema, mi perdevo nelle facce dei grandi attori. Non mi affascinava tanto la popolarità del personaggio, l’aspetto cosiddetto divistico, quanto i dettagli del viso e la sua espressione mimica. Nei miei video non riprendo mai il paesaggio naturale; piuttosto, inquadro lo scenario emotivo dell’incontro tra me e i miei interlocutori.

![Valerio Rocco Orlando, Promenades, 2012. MACRO, Rome.]()

Valerio Rocco Orlando, Promenades, 2012. MACRO, Rome. Photo: Giorgio Benni.

Una sorta di cartografia emozionale, in cui il corpo umano – il volto – diviene mappa.

Esatto. E tutti questi volti, un giorno, quando riuscirò a mostrarli insieme, formeranno un paesaggio estremamente variegato, particolare e universale, legato alle esperienze vissute in prima persona in luoghi tanto diversi. Quando Heidegger parla della poesia di Friedrich Hölderlin, utilizza una metafora a cui sono molto affezionato, quella delle “lente passerelle”. Si tratta di ponti che non sembrano tali, poiché fanno parte dei luoghi tra cui stabiliscono il passaggio. L’esplorazione umana che compio attraverso il mio lavoro avviene percorrendo a fianco dell’altro queste “lente passerelle”. Esse connettono diversi elementi del paesaggio, favoriscono l’incontro, il dialogo e l’apertura – tutti processi che richiedono tempo e presenza costante, ma soprattutto fiducia reciproca, osservazione e ascolto. Si tratta, per l’appunto, di un viaggio lento, graduale.

Passiamo al ciclo di video sul tema dell’educazione, dal titolo What Education for Mars?

L’intero progetto è nato nel 2011, quando sono stato invitato a una residenza di sei mesi a Roma da Nomas Foundation. L’idea era quella di indagare le relazioni tra studenti e insegnanti all’interno del sistema educativo nazionale. A Roma ho dunque lavorato con gli allievi e i docenti del Liceo Artistico De Chirico, nella periferia cittadina. Gli stessi studenti sono poi diventati la mia troupe: mi hanno aiutato a sviluppare il progetto, a scrivere le domande, a realizzare le interviste e a fare le riprese. Ho presentato lo stesso progetto a Cuba, in occasione della XI Bienal de La Habana nel 2012 e, nell’estate del 2013, sono stato invitato come Visiting Professor alla Valley School della Krishnamurti Foundation, una scuola nella foresta indiana fuori Bangalore. Qui gli studenti vivono in un campus insieme agli insegnanti; non ci sono libri di testo, le classi sono verticali e raccolgono ragazzi di età, etnie e background diversi. L’insegnamento avviene unicamente attraverso il dialogo. Nel corso della mia permanenza in India, ho prodotto un nuovo video – il terzo capitolo della serie – con i giovani che seguivano il workshop. Durante le lezioni ho posto degli interrogativi, e al termine del soggiorno abbiamo girato le interviste. In occasione della mia mostra personale al Museo Marino Marini di Firenze, la prossima primavera (dal 20 febbraio al 9 maggio, nda), verrà presentato per la prima volta il ciclo nella sua interezza. Inoltre, grazie alla collaborazione con il dipartimento educativo del Museo, verrà organizzato all’interno degli spazi espositivi un laboratorio speciale della durata di due mesi che coinvolgerà un gruppo variegato di studenti fiorentini. L’obiettivo è quello di costruire insieme ai ragazzi un libro d’artista, un’opera collettiva che sia il risultato dell’osservazione dei video in mostra.

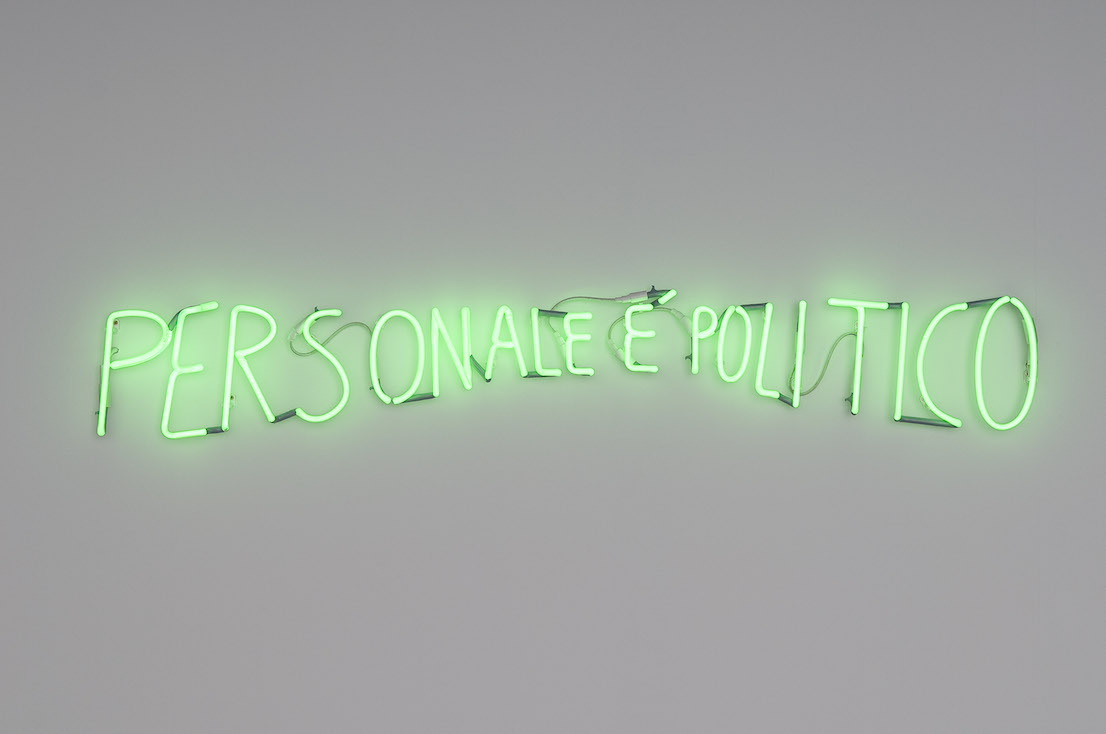

![Valerio Rocco Orlando, Personale è Politico, 2011. Nomas Foundation Collection. MACRO, Rome.]()

Valerio Rocco Orlando, Personale è Politico, 2011. Nomas Foundation Collection. MACRO, Rome.

Oltre alla personale al Museo Marino Marini, quali sono i tuoi progetti futuri?

Fino al 6 gennaio si potrà vedere PAC di Milano una collettiva (ora conclusa, nda) dedicata alle interferenze tra arte e cinema in Italia, a cui partecipo con una chicca che pochi hanno visto: The Screen, un film del 2004 che vanta la prima apparizione sullo schermo di Alba Rohrwacher. Poi terrò un paio di mostre in due musei in Corea (tra cui The Sphere of the Beetween, in corso fino al 28 febbraio presso la Korea Foundation di Seul, nda), dove rimarrò fino a fine anno, grazie a un’International Artist Fellowship al MMCA di Seul. Per poi riprendere, finalmente, il progetto in Israele. Ti confesso che non è facile tenere insieme le fila di tutto. In ogni caso, sono sempre più consapevole di come questa strada sia in linea con la mia natura, e soprattutto quanto ogni nuovo incontro sia vitale per riattivare e coltivare questo percorso condiviso.

/

Portraits in Motion

The work of the artist Valerio Rocco Orlando, born in Milan in 1978, explores the landscape of the encounter and the relationship with the Other with surprising delicacy. Video is his favorite medium: his camera penetrates, through extreme close-ups, into the depths of the expressions and the lines on the faces of the people he portrays. Orlando’s practice—a contemporary form of the Socratic Method—is based on dialogue, on an intimate exchange with the interlocutor. After studying dramaturgy in Milan and film directing in London, he has lived in Rome, New York, Cuba, Bangalore, Tel Aviv and Seoul, moving from residence to residence and making travel the indispensable condition of his research. I met Valerio a few months ago in Milan, shortly after his return from Israel, the place where he is going to shoot his next film.

Interfaith Diaries is the title of the project on which you have been working during your residency at Artport Tel Aviv, since May 2014. As a result of the conflict that broke out in the Gaza Strip in July of the same year, you were forced to leave Israel and interrupt your work. Can you tell me more about this experience?

Interfaith Diaries is a project that I have been thinking about for a long time. I was raised as a Catholic, I’m thirty-six years old and in this phase of my life I am calling my relationship with God completely into question. There are moments in which I think it is fundamental to raise questions of this kind. For some time I’ve been keeping a diary, something that allows me to investigate my inner world. Before the invitation from Vardit Gross, director of Artport, I’d never been to Israel. I saw it at once as an opportunity to produce a new work on just this theme of spirituality. So I set off with the best intentions. Initially, I thought Jerusalem would be the ideal place for this research. In reality, it’s not like that. The Israeli state is very young, social progress is really rapid and people’s relationship with religion is fairly controversial. And then I didn’t want to explore the reality of the orthodox communities. On the contrary, what I wanted to look at was the everyday lives of ordinary people and the way in which they relate to their own spiritual dimension.

![Valerio Rocco Orlando, Lover’s Discourse (New York), 2010.]()

Valerio Rocco Orlando, Lover’s Discourse (New York), 2010.

So people who are asking the same questions as you, who mirror your personal experience.

Exactly. Individuals who are in some way close to me. Even though my work takes me to faraway places—Korea, Iceland, the United States, Cuba, India or, as in this case, Israel—I always try to collect and tell stories that are close to my own experience. Ever since my arrival in the Middle East, I’ve been explaining to everyone that it was not my intention to deal with the conflict or the situation of the religious minorities; rather I wanted to interact with those who like me are questioning deeply their own relationship with the spiritual dimension. When I presented the project in Tel Aviv, at the beginning of June last year, I started by saying: “I’m looking for someone who is on some sort of spiritual journey.” This open call included many possibilities: I wasn’t going to look for a specific type of person. I was open to different stories and I started to frequent alternative situations. Among them, a rather special synagogue, where the rabbi welcomed those who no longer identified with their community of origin as a result of a series of personal choices. For example, lesbian couples with children: stories quite different from the classic orthodox family. To tell you an anecdote, among these people I met a young man of twenty-eight-year who decided to take part in the project and share his experience. Yarden is originally from a kibbutz near Tel Aviv, where years ago he got married and had a child. At a certain point in his life he recognized and accepted his homosexuality, deciding to leave his family and move to the city. Now he lives in Tel Aviv with a partner and attends the synagogue that I was just talking to you about. Yarden told me that as a boy he used to walk in the fields close to his house, at night, and pray. Something that he can no longer do and for which he feels a certain nostalgia. When I asked him, for this new film, to think of a place that represented his inner path, he spoke to me of these walks. The idea is to shoot a nighttime stroll in one of those fields—a long tracking shot in which he is walking hand-in-hand with his son. A choice that springs from constant dialogue and mutual trust. I won’t hide from you my enthusiasm about this meeting. Anyway, we haven’t been able to shoot this scene yet because, when the war broke out, Yarden was called up to the reserves and left for Gaza.

What was it like living in Israel in the middle of the conflict, even if only for a short time?

I never feared for my safety. However, everyday life was a complete shambles, even though no one in Tel Aviv was hurt. Those two months were a period of preparation and research for me. I knew that I wouldn’t do any actual shooting or concretely realize the project. Rather, I was trying to work out how to develop it. For the first time for ten years I decided to deal with an actor, choosing to work with Saleh Bakri. Born in Palestine, but with Israeli citizenship, he was one of the signatories of the manifesto of the BDS, a movement founded by some Palestinian intellectuals that boycotts Israel, refusing to take part in government-funded productions. It was very difficult to get in touch with Saleh and to start working with him: the funds for my residence, in fact, come from an American foundation. After a long series of emails, telephone calls and failed attempts to meet him, one day, finally, Saleh agreed to see me. He invited me to his home, in Haifa, a city in the north of the country, close to Lebanon. The war had already started and the journey was fairly complicated. I remember the marvelous view of the port from his terrace. There I started to explain my ideas, speaking excitedly, in the hope of being able to stir his curiosity in a short space of time and persuade him to participate. After listening to me without interruption, he offered me an espresso, saying: “Valerio, my friend, relax!” Then I realized there was no need to convince him. He had found out all about me and had already decided to take part in the project. That day we decided to write the thing together. I asked him not so much to play a part or a character as to be himself, inviting him to be my guide, a bit like Virgil was for Dante. He was supposed to help me to meet people, Israelis and Palestinians, establishing a dialogue with the participants. We started to define the script together, until I realized that it was impossible to go ahead and so, reluctantly, decided to postpone the shooting. Not just because of the obvious difficulties on the emotional and relational level. Many of the places that we had to go to were too close to the conflict. There was, for instance, the Negev Desert, not far from Gaza, where I’d have liked to shoot a central scene of the film. I had hired a car, and driving along the road we encountered a series of tanks that were being transported in preparation for the ground attack. Sleeping in the desert, we could hear the noise of the bombs going off. The project was suspended and the production budget frozen. For the moment we are working at a distance. My intention is to go back there next year (in 2015, author’s note) to reestablish contacts and carry on with the work.

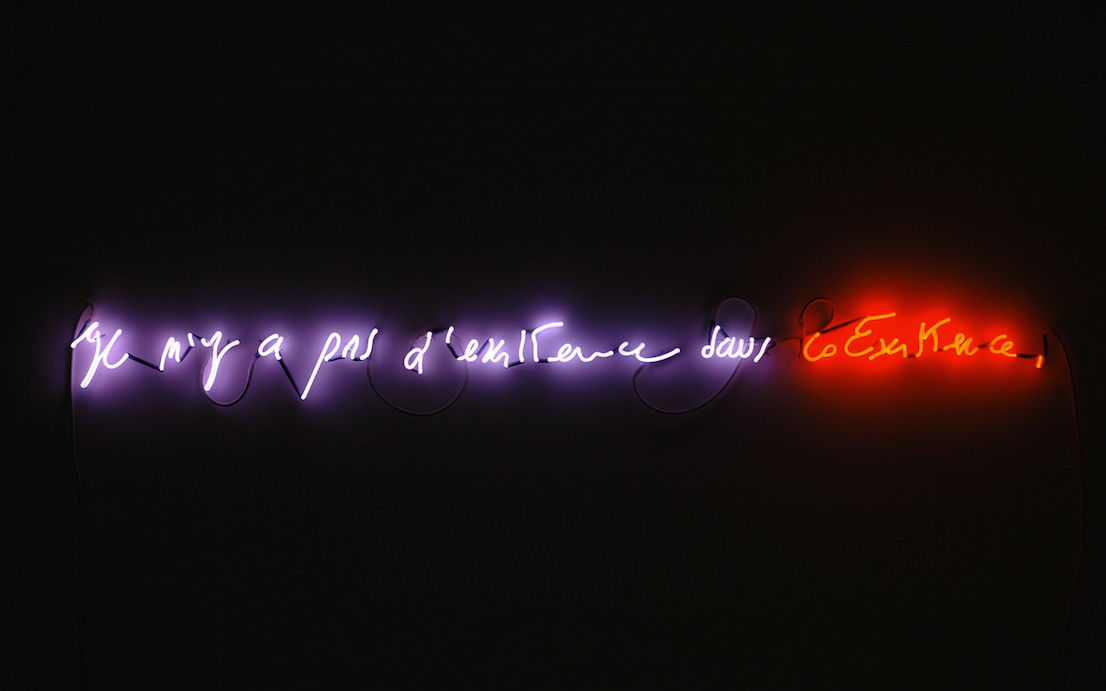

![Valerio Rocco Orlando, Coexistence, 2010.]()

Valerio Rocco Orlando, Coexistence, 2010. Leksell Collection, Stockholm.

What form will the work take in the end? Will it be a video installation?

Interfaith Diaries will be different from my other works. As I was telling you, in the first place I’ll be working with an actor—and I’m sure that Saleh Bakri is the right choice. He’s much loved by the people of the place, a lucid and well-informed activist, a person who knows how to listen. It will be a film, a feature-length movie, that can be shown in a museum or at a festival or in a movie theater. There won’t be much dialogue, I’m imagining scenes with long walks. I believe that the spiritual quest at the base of this work, in its final form, will emerge above all from silence. I see this work as a sort of personal pilgrimage, on which I am accompanied by individuals with whom I share a certain feeling and the same interest in inner analysis.

You have studied in Milan and London. Directing is at the center of your work. In your videos, you gather a series of stories and guide the contributions of the people you speak to in your “inquiries,” each turning on a specific theme: love, education, religion. The end result is a harmonious orchestration of faces and extreme close-ups. I’m thinking in particular of The Sentimental Glance (2002-07), one of your earliest video installations, composed of portraits in motion of six young women connected with your own life.

In the cinema and the theater I’ve always been fascinated by the expressive possibilities of the human face. So in a sense the portrait has always been my main field of research. The face provides an opportunity for dialogue and exchange. All my videos are like self-portraits, even though I never appear in the scene and you never hear my voice. Yet my presence is tangible. Perhaps, the basis of my directing in all these works—and I’m not speaking just of the videos, but also of my books, photographs and installations—lies in the empathy that is established between me and the subject. For me, art is a process of shared understanding, of development. In this sense, empathy is an extraordinary vehicle for learning.

Editing, in your videos, plays a fundamental role: by selecting and putting together the testimonies of the individuals with whom you establish a relationship, the work is charged with a symbolic, emotional value. Which means your works are light years away from pure sociological research.

I don’t make documentaries: my research is not at all scientific. I start out in an emotional and instinctive way from a need for self-understanding; then the encounters with the people I talk to show me the way forward. I ask questions and connect up the answers: my idea of art is a proposal that remains open. Editing is the means by which, as an artist, I make choices; one of these can be to link one story with another by creating, for example, a shot-reverse shot that in reality never took place. This is how my subjectivity emerges. The heart of the directing process lies in the editing stage, so no one but me can edit my works. It is a question of assuming responsibility, in a way.

![Valerio Rocco Orlando, Amalia, 2006.]()

Valerio Rocco Orlando, Amalia, 2006.

And what role does the viewer play in your work?

A fundamental one. My aim is for the questions I raise to involve and stimulate the viewer, so that the latter can become part of the platform of reflection, dialogue and exchange that is at the base of my work.

You often cite Jean-Luc Nancy and his notion of “being singular-plural,” that is to say the idea that the essence of our existence is “co-existence,” living with others. In your works you explore the concept of identity and try to understand to what extent the individual is influenced by the sense of belonging to a more or less small community, like the pairs of lovers in Lover’s Discourse (2010), the students in What Education for Mars? (2011-13) or the artists in residence of The Reverse Grand Tour (2012).

First of all, I’m not interested in working with enormous communities because what I have to maintain—and I’m firmly convinced of this—is the personal one-to-one relationship. For me, the concept of identity is closely bound up with that of community, and I think that art and artists have great possibilities to act on this level. Intimacy becomes the key of access to truth.

We could say that the relations you establish with people to create your works contributed to the definition of your identity.

Yes, as an individual and an artist. This has been happening since The Sentimental Glance, which is a sweeping depiction of my growing up, a self-portrait through the faces of some young women whom I’ve known over the course of several years. It’s a different kind of production from the more recent ones, in which I deal with remote and exotic communities—it suffices to think of the Indian forest where I worked last summer with the students of the Valley School. However, I don’t see major differences with respect to the methodology of the other works. In all of them the personal character is strong. For me they are a single, grand work. In fact I dream of one day showing all these videos and films together. I’d like the viewer to enter this labyrinth of stories: some of them whispered, others spoken out loud, but never shouted, intimate in character, and at the same time social. I like the idea of involving the public in a broad dialogue, in part autobiographical, but one that in fact recounts the life of others.

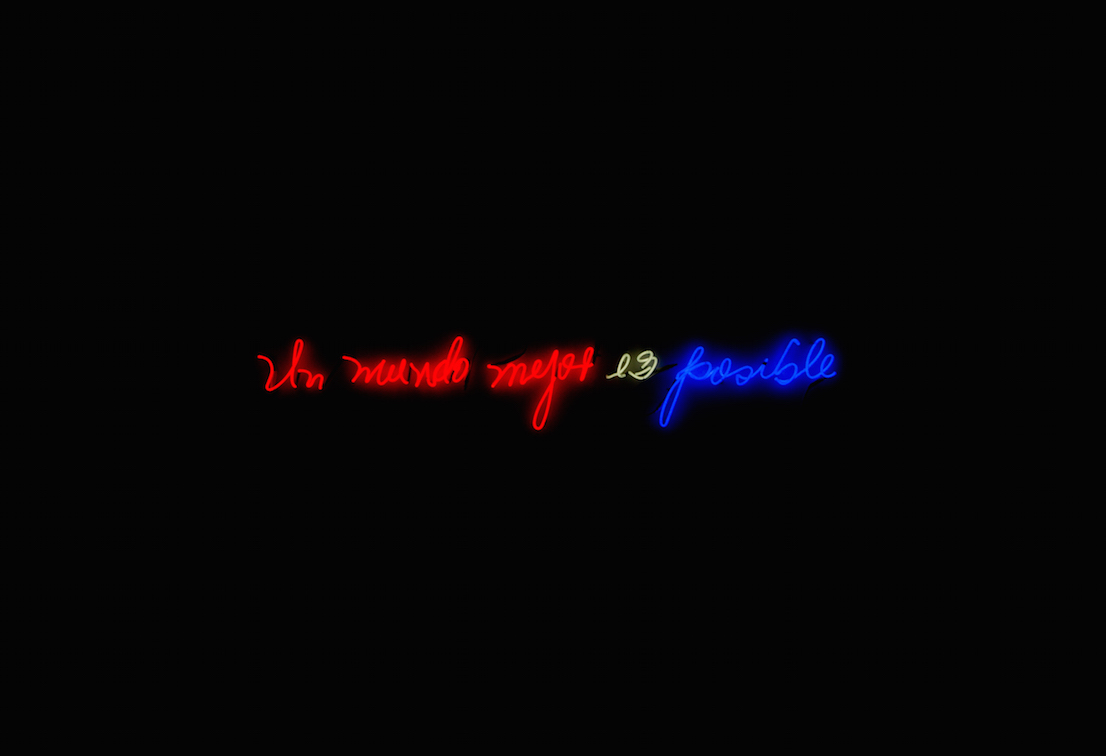

![Valerio Rocco Orlando, Un mundo mejor es posible, 2012.]()

Valerio Rocco Orlando, Un mundo mejor es posible, 2012.

I see your work as a form of maieutics, of the Socratic Method: dialogue, on which your practice is founded, becomes a means of growth and understanding.

That’s exactly right. Dialogue is a way of looking one another in the eyes, listening to and entering into deep contact with the other. Martin Buber speaks of the “sphere of the between,” of the space that is created between two people in the act of meeting. He argues that when two human beings find themselves face to face something unique happens, which helps to reshape the identity of the individual. I’m convinced of this: through a profound exchange with the other we continually bring ourselves into question; without it, I’d be like a painter without muse, canvas and paints.

To go back to the principal role that the human face takes on in your videos, on more than one occasion you have compared the faces filmed by your camera with landscapes. Giuliana Bruno, with her Atlas of Emotion, constitutes one of your literary references. I’m deeply fascinated by the connection between body and landscape, anatomy and geography, on which your formal language seems to be based.

I’ve always thought about the face in relation to space. At the moment in which I confront the other, the face becomes an organic tissue capable of registering a range of emotions: in this sense it becomes landscape. I want my videos to be shown on large screens or through projections on a large scale not for any simple formal reason, but because the face, through the close-up, the framing of the expression at really close range, becomes a place in which the viewer can lose himself. These requisites favor a sort of emotional immersion, of a cathartic nature. Ever since I was young, in the movie theater, I would lose myself in the faces of the great actors. What fascinated me was not so much the popularity of the personage, his or her so-called star quality, as the details of the face and its mimicking of expression. In my videos I never shoot the natural landscape; instead, I frame the emotional scenery of the meeting between me and my interlocutors.

A sort of emotional cartography, in which the human body—the face—becomes a map.

Exactly. And all these faces, one day, when I manage to show them all together, will form an extremely variegated, particular and universal landscape, linked to my personal experiences in very different places. When Heidegger speaks of the poetry of Friedrich Hölderlin, he uses a metaphor of which I’m very fond, that of the “slow pathways.” These pathways are bridges that do not seem to be bridges, as they are part of the places between which they form a passage. The exploration of humanity that I carry out through my work is made by taking these “slow pathways” alongside the other. They connect different elements of the landscape, favoring meeting, dialogue and opening—all processes that require time and constant presence, but above all mutual trust, observation and listening. It is, precisely, a slow journey, made step by step.

![Valerio Rocco Orlando, 16.12, Roma, 2011]()

Valerio Rocco Orlando, 14.12, Roma, 2011.

Let’s move on to the series of videos on the theme of education, entitled What Education for Mars?

The whole project was born in 2011, when I was invited for a residency of six months in Rome by the Nomas Foundation. The idea was to investigate the relations between students and teachers within the national system of education. So in Rome I worked with the students and teachers of the Liceo Artistico De Chirico, in the suburbs. The students then became my crew: they helped me to develop the project, to write the questions, to carry out the interviews and to do the shooting. I presented the same project in Cuba, on the occasion of the 11th Bienal de La Habana in 2012 and, in the summer of 2013, I was invited as visiting professor to The Valley School run by the Krishnamurti Foundation, a school in the Indian forest outside Bangalore. Here the students live on a campus with the teachers; there are no textbooks, the classes are vertical and made up of children of different ages, ethnic groups and backgrounds. Teaching is done exclusively through dialogue. Over the course of my stay in India, I made a new video—the third chapter of the series—with the young people who attended the workshop. During the lessons I raised questions, and at the end of my stay we filmed the interviews. At my solo exhibition at the Museo Marino Marini in Florence, next spring, the series will be shown for the first time in its entirety. In addition, in cooperation with the museum’s educational department, a special two-month-long workshop will be held in the exhibition spaces that will involve a varied group of students from Florence. The aim is to create with them an artist’s book, a collective work that will be the result of their observation of the videos on show.

In addition to the solo exhibition at the Museo Marino Marini, what are your future projects?

Until January 6 you can see a joint exhibition at the PAC in Milan (now closed, author’s note) devoted to the interactions between art and cinema in Italy, to which I’m contributing a little gem that few have seen: The Screen, a film from 2004 that can lay claim to being Alba Rohrwacher’s first appearance on screen. Then I’ll be holding exhibitions at a couple of museums in Korea, where I’ll be staying until the end of the year, thanks to an International Artist Fellowship at the MMCA in Seoul. After which I’ll go back, at last, to the project in Israel. I’ll admit to you that it’s not easy to keep it all together. In any case, I’m more and more conscious of the fact that this path is in keeping with my nature, and above all how every new encounter is vital to reactivating and cultivating this shared process.

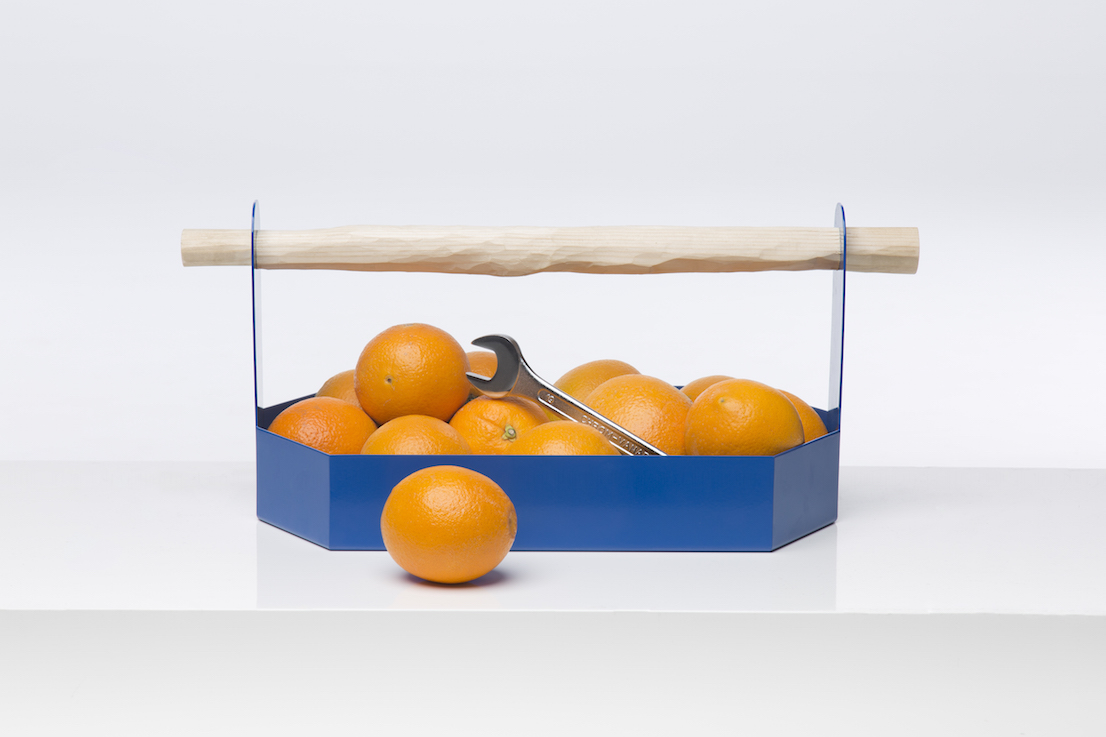

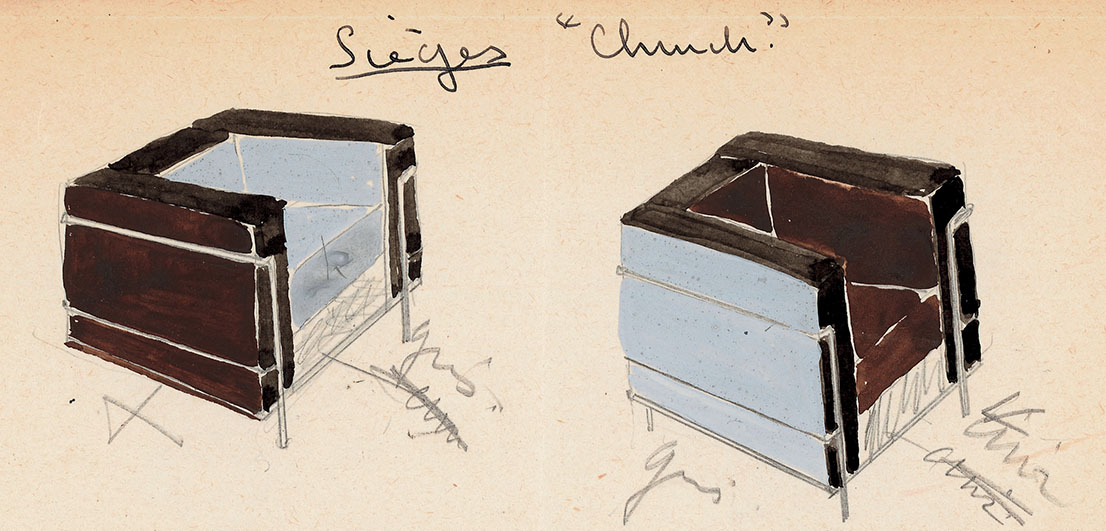

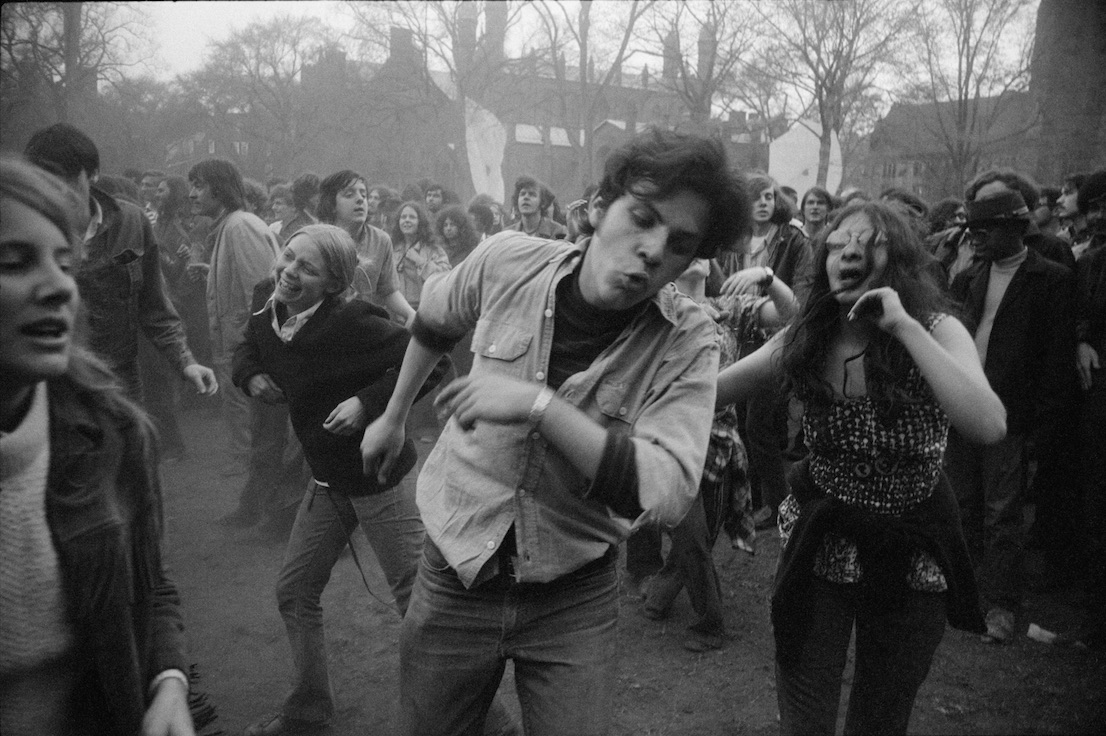

![Richard Nixon Campaign Rally, New York [Rassemblement de campagne de Richard Nixon, New York], 1960. Garry Winogrand. Garry Winogrand Archive, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona. © The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco](http://www.klatmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Klat_Garry_Winogrand_19.jpg)