(english text below)

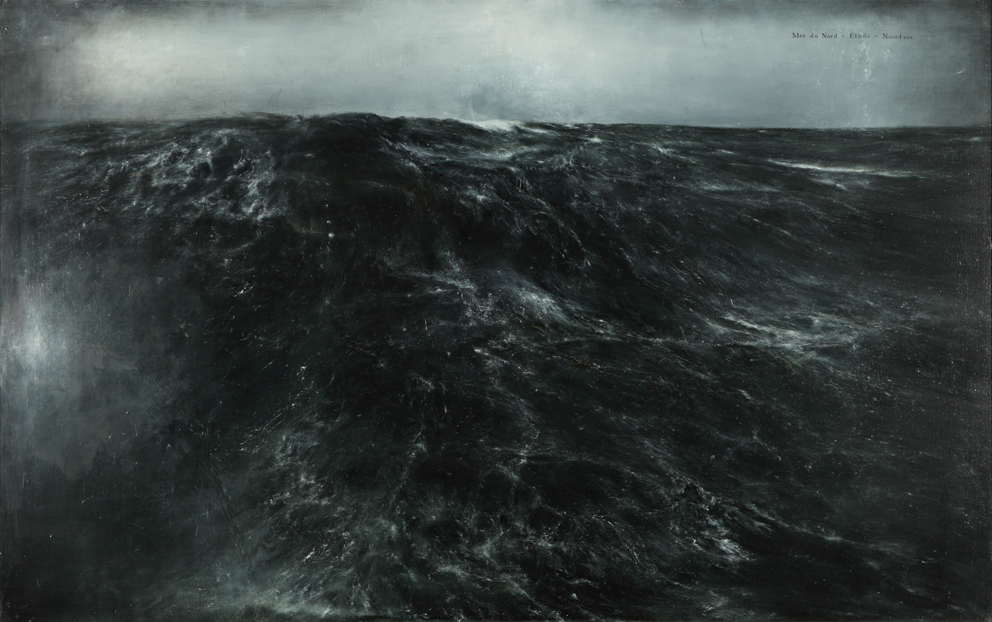

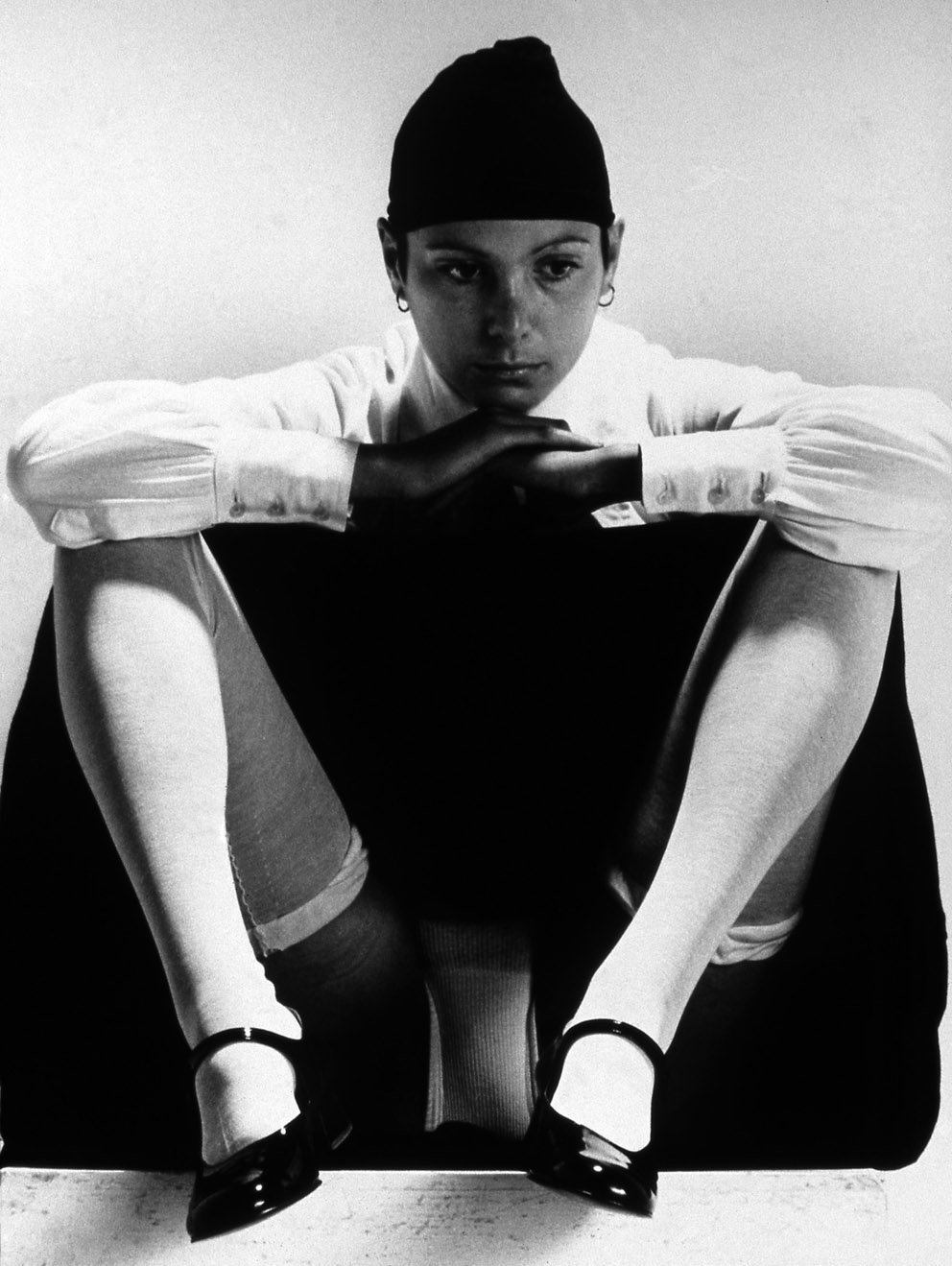

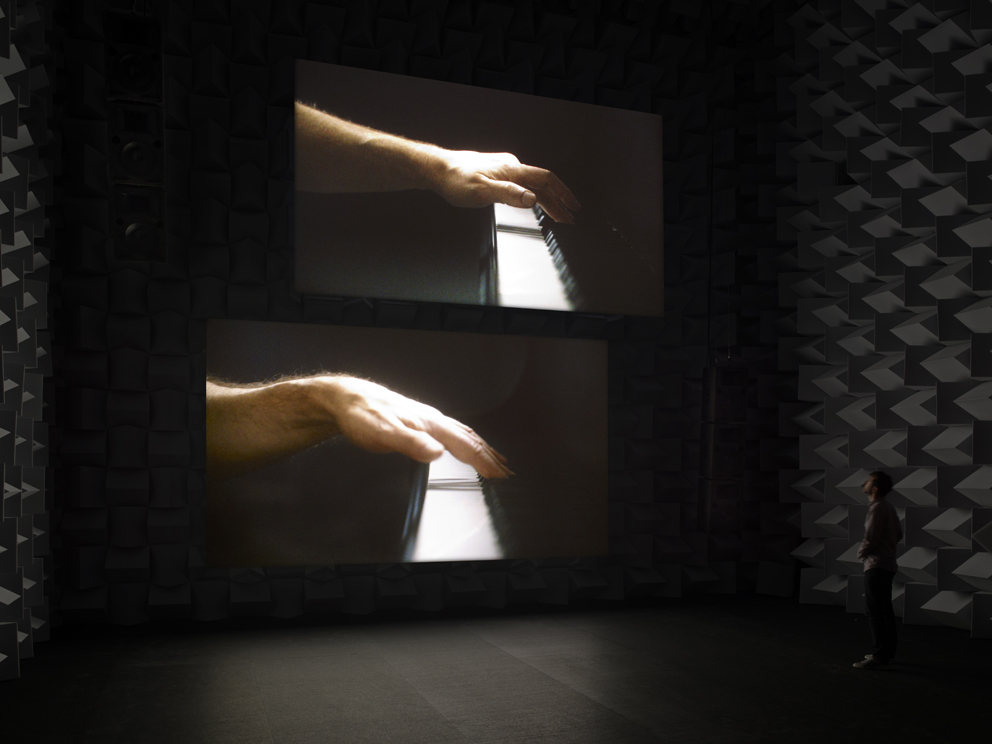

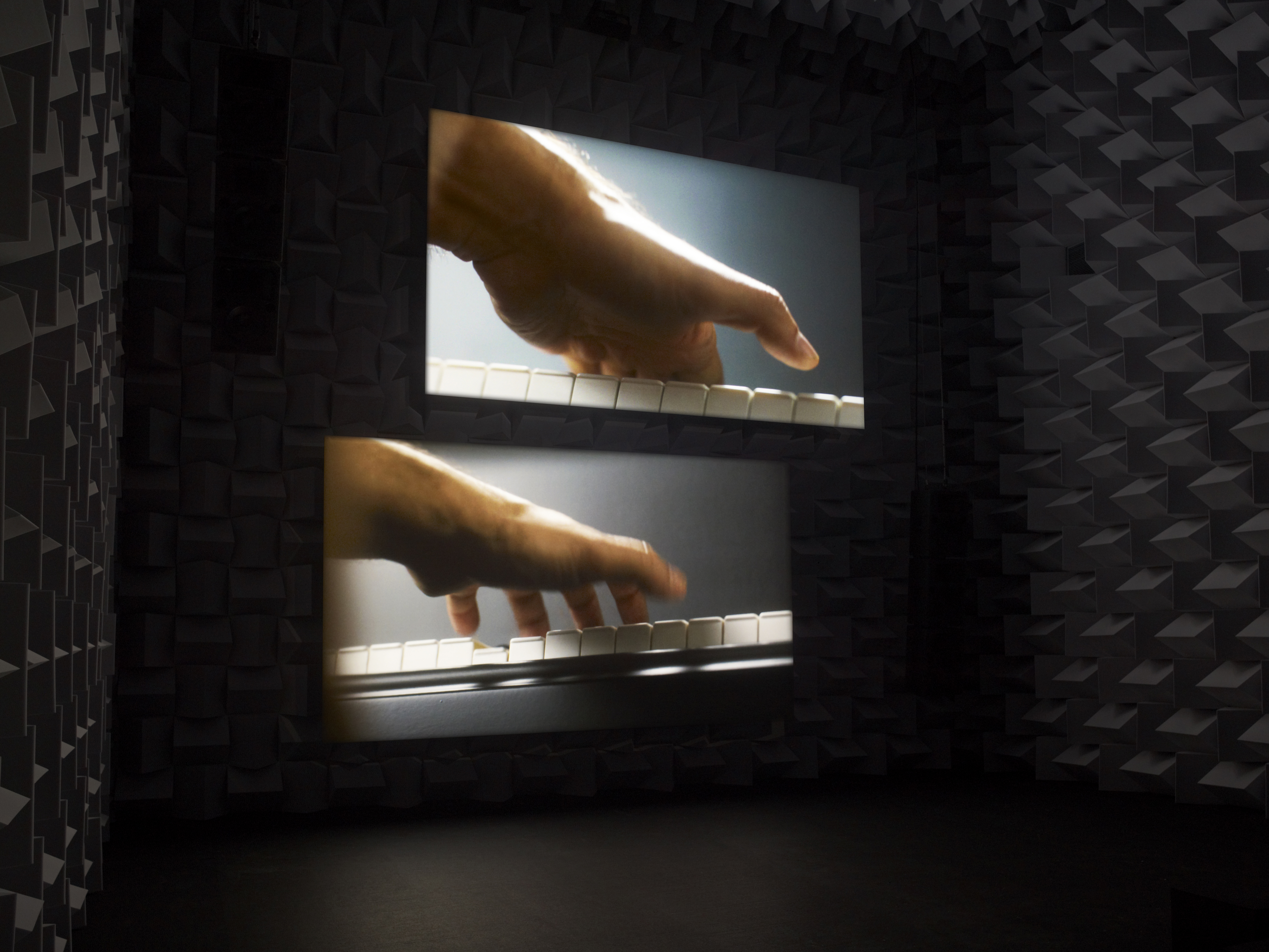

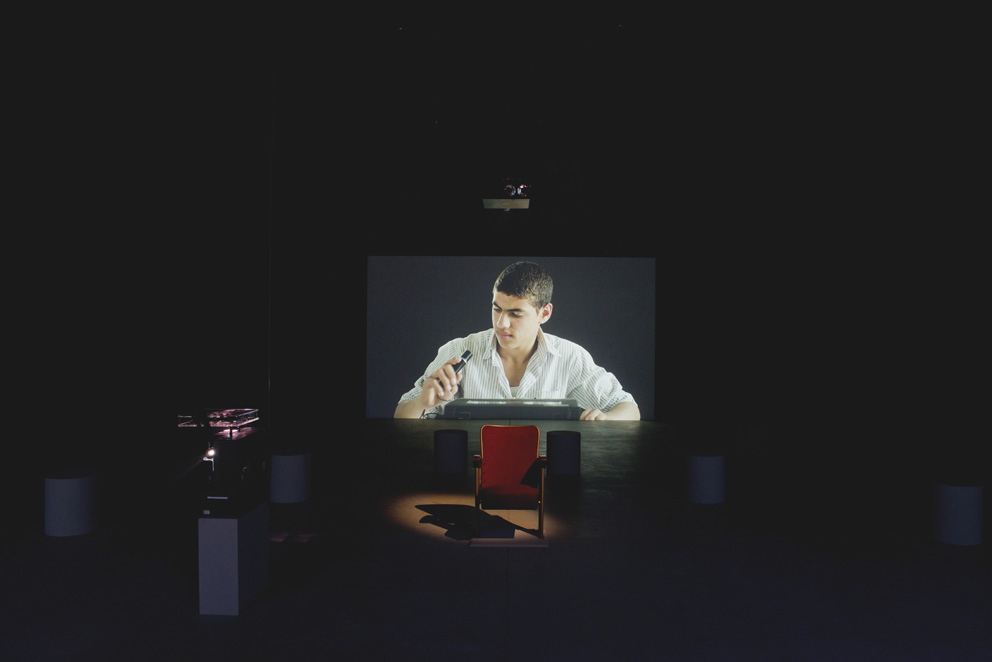

Foto di /Photo by Maria Ziegelböck

A grande richiesta, abbiamo deciso di pubblicare sul sito le lunghe e straordinarie interviste apparse sul magazine cartaceo dal 2009 al 2011. Quaranta trascinanti conversazioni con i protagonisti dell’arte contemporanea, del design e dell’architettura. Una volta alla settimana, un appuntamento da non perdere. Un regalo.

Oggi tocca a Martino Gamper.

Paolo Priolo

Intervista di Laura Garbarino. Klat #02, primavera 2010.

Martino Gamper, una delle personalità più intriganti del mondo del design contemporaneo. Ron Arad lo ha definito «a wizard, inventive chef», la sua amica e grafica Kajsa Stahl un «last minute perfectionist». Il suo metodo ha un non so che di geniale, che spazia dall’artigianato all’improvvisazione, al concettuale. In ogni suo atteggiamento, nei progetti, a cena con gli amici, nelle sue teorie più varie, la spontaneità e l’unicità sono gli elementi che maggiormente lo contraddistinguono.

Ciao Martino, come ti definisci e in quale ordine? Designer, artista, chef…

Professionalmente mi ritengo un designer, ma il mio approccio al progetto è per certi aspetti artistico. Lavoro anche senza committenza. Non avere committenza può essere un valore, perché sei più libero, ma a volte il nulla spaventa. Il mio metodo ha molto a che fare con la ricerca, meno con la creazione, che è un po’ la differenza tra un designer e un artista. È la funzionalità a distinguere i due ambiti. L’arte può essere irrazionale, non deve spiegare nulla. Io, al contrario, devo poter definire quello che creo e soprattutto voglio che le mie sculture, i miei oggetti, i miei mobili siano usati. Per rispondere alla tua domanda: designer, artigiano, artista e chef.

Italiano di nascita: Merano, 1971. Londinese d’adozione: hai studiato al Royal College e sei rimasto in Inghilterra. Perché Londra?

Londra innanzitutto per formazione. Sono scappato abbastanza giovane dall’Italia. Dopo il mio apprendistato come falegname, all’età di diciannove anni, ho lasciato le montagne e l’Italia per il mondo. Dove sono cresciuto mi sentivo isolato. Amo le montagne, ma non ti lasciano vedere cosa succede al di là delle cime.

Tra Merano e Milano, dove hai fatto un’esperienza di due anni nello studio di Matteo Thun, c’è stata l’Accademia di Vienna e numerosi viaggi in giro per il mondo. Penso che vivere in città diverse, muovendo il proprio pensiero nel mondo, abbia un’influenza determinante sul carattere di una persona, sul suo modo di essere. Cosa ti ha lasciato Vienna e il nomadismo di qualche viaggio?

Vienna mi ha influenzato e mi ha lasciato la grande cultura dell’umanesimo, l’inizio del design craft e lo Jugendstil, la Secessione, ma anche l’arte degli anni Settanta e Ottanta, l’Aktionismus Viennese, la cultura del cibo e del caffè. L’esperienza nello studio di Matteo Thun è stato il primo contatto con il design industriale. È stata una esperienza utile, impegnativa e formativa, poiché il mondo del lavoro è astruso per chi esce da un’accademia o dall’università. Direi che Thun mi ha insegnato un metodo, ma mi ha anche mostrato quello che non volevo fare, aiutandomi a trovare una mia strada, una mia dimensione, rendendomi consapevole che non volevo lavorare per qualcun altro, ma solo per me stesso. Prima di studiare a Vienna, ho viaggiato due anni in giro per il mondo: Stati Uniti, America Centrale, Guatemala, Messico, Hawaii, Nuova Zelanda, Australia, Filippine, Thailandia. Ognuno di questi posti mi ha lasciato qualcosa, sarebbe lungo ricordarli singolarmente, ma tutti hanno concorso a definire quello che sono oggi.

Come sceglievi le tue mete?

Avevo un biglietto aereo “round the world” che permetteva di fare soste in giro per il mondo, sempre in una direzione, senza mai tornare indietro, quindi a volte erano scelte obbligate. Cosa ho imparato da questo viaggio? Che il mondo è pieno di possibilità e devi sempre essere tu a scegliere. Il mondo non sceglie per nessuno, quando viaggi devi fare una scelta ogni giorno, dove andare, quanto stare.

E l’Italia cosa rappresenta per te? Come la vedi ora che vivi all’estero?

L’Italia resta un punto di riferimento, con la mia casa, la famiglia, e un certo senso di appartenenza. Quello che accade nel Paese non si riesce a comprendere dall’estero, sembra che i media parlino soltanto di cose superficiali o di scandali e che gli italiani si riconoscano in questa cultura dell’apparire, vuota di contenuti e stanca. In realtà, penso che la mentalità italiana dei giovani si sia aperta negli ultimi anni, alla ricerca di un cambiamento che il Paese non offre. Hanno cominciato a viaggiare di più e molti, prima per necessità e ora anche per scelta, cercano opportunità all’estero.

Cosa leggi per tenerti aggiornato?

Leggo il New Yorker, il settimanale tedesco Zeit e quotidianamente consulto BBC online, ma butto un occhio anche a corriere.it, repubblica.it e stol.it, un sito locale di Merano, così passo dal mondo all’Italia, al mio paese.

![Martino Gamper, 100 Chairs in 100 Days and its 100 Ways, 2005-2007. Photo: Åbäke, Martino Gamper]()

Martino Gamper, Backside, 100 Chairs in 100 Days and its 100 Ways, 2005-2007. Photo: Åbäke, Martino Gamper.

Pensi mai di tornare in Italia?

Per vivere no, almeno per ora, ma ho molte occasioni che mi ci portano: dalla vacanza con gli amici, al lavoro stesso. E questo mi fa piacere.

100 Chairs in 100 Days: la tua più grande esposizione, transitata da Londra alla Triennale di Milano. La mostra è un’esemplificazione della tua capacità creativa. Ognuna delle sedute ha una sua personalità, sembrano ritratti, collage tridimensionali. Quando l’ho visitata, ho avuto l’impressione che avessi infinite combinazioni a disposizione per arrivare alla realizzazione di ciascuna sedia. Come hai scelto certe combinazioni piuttosto che altre? C’è stato uno slancio creativo, immediato, che ti ha guidato nella scelta delle combinazioni?

Le 100 sedie sono i progetti finiti, ma da quelle idee ne sono nate altrettante. La limitazione temporale rendeva il progetto intrigante. Le ho effettivamente realizzate in 100 giorni, non consecutivi, ovviamente. Mi è piaciuto tradurre le mie idee in uno spazio tridimensionale, creando una sorta di sketchbook.

Parlami dei titoli che hai dato a ogni seduta. Sono spontanei o propongono una chiave di lettura?

Solo nel momento in cui ho redatto il catalogo della mostra mi è stato chiesto di dare dei titoli, quindi arrivano a posteriori. In alcuni casi, non ho potuto fare altro che associare le sedie a delle persone, umanizzandole, nonostante non le abbia pensate come dei ritratti. In altri casi, ho voluto ironizzare su riferimenti storici e personaggi di fantasia come Barbapapà in Vienna, Sonet Butterfly o Charles and Ply.

Quando cominci a lavorare, assemblando due sedie, hai già in testa un’idea del risultato? Mi è capitato di vedere un video su YouTube, the making of aradson, che ti riprendeva con un collaboratore, Harry, in fase progettuale. Stavate perdendo l’idea di partenza, schizzata sul tavolo a matita, quando a un certo punto hai detto: «I want to save it». Cosa significava in quel momento esatto?

È facile trovare una tipologia di sedia su cui cominciare a lavorare, ma se non riesco a finirla mi areno, allora passo ad altro, e riprendo in mano il lavoro in un secondo momento. Non sono così legato al punto di partenza, ma quando ho a che fare con un prototipo devo aver provato almeno a realizzarlo. In quel caso, volevo salvare l’idea iniziale, anche se poi il risultato era diverso da quello che avevo in mente…

Il tuo modo di operare restituisce vita agli oggetti dimenticati e allo stesso tempo sacrifica quella di oggetti che hanno fatto storia, come gli arredi di Gio Ponti e di Carlo Mollino. È un tentativo d’interazione e re-interpretazione di quelle opere o un intervento irriverente verso alcuni maestri?

Penso che per creare qualcosa di nuovo sia necessario decostruire l’esistente o dimenticare il passato. Credo sia ipocrita e sbagliato imitare un maestro o voler diventare un nuovo Ponti. Per me, è importante “tagliare a pezzi” l’esistente: lo faccio con rispetto, lo vedo come una sorta di processo di conoscenza. Non ho bisogno di partire dalla materia prima pura. Anche ciò che è stato già lavorato o utilizzato, e ha una sua forma, può essere visto come materia prima da cui ricavare un altro oggetto. Non è una questione di “troppo rispetto”, ma di evoluzione del pensiero. L’eccessivo rispetto non ti fa andare avanti. Nella prima performance che ho proposto a Design Miami/Basel, nel 2008, If Gio only knew, ho utilizzato gli arredi dell’Hotel Parco dei Principi a Sorrento, disegnati da Gio Ponti. Ero un po’ titubante, influenzato appunto da una forma di eccessiva riverenza. Alla decima opera mi sono lasciato andare, preso dall’entusiasmo di cambiare destino a quegli oggetti. Ho pensato che, in realtà, c’era poco di Ponti in quegli arredi, si trattava di una produzione in serie, anzi industriale, destinata a un albergo. Non volevo distruggere Ponti perché è Ponti. C’era certamente della provocazione, e non è un caso se ho scelto di proporre quella performance a Basilea, visto che in una fiera che si definisce di design contemporaneo la maggior parte degli stand proponevano Gio Ponti e design anni Cinquanta e Sessanta. Non vedevo spazio per i giovani…

![Martino Gamper, 100 Chairs in 100 Days and its 100 Ways, 2005-2007. Photo: Åbäke, Martino Gamper]()

Martino Gamper, Sonet Butterfly, 100 Chairs in 100 Days and its 100 Ways, 2005-2007. Photo: Åbäke, Martino Gamper.

Parlando di mercato del design, cosa pensi di Ron Arad e Marc Newson, oggi tra le star del design contemporaneo? Sono ancora dei designer o sono degli artisti?

Sono un po’ perplesso, non tanto sulla loro identità di designer, quanto sul fatto che si stia parlando di design o di mercato. Ron Arad è stato mio professore a Londra e Vienna, lo stimo molto. Un giorno in classe disse: «Farò la prima sedia su cui non ci si potrà sedere». Da lì, per me non era più design. Ron ha voluto shockare il mondo del design e del mercato. Ha voluto scegliere per il mercato per paura che il mercato scegliesse per lui, arrivando quasi a controllarlo.

Hai mai fatto produzioni industriali?

Mi fai la domanda al momento giusto. Sono in procinto di tentare la prima produzione industriale, non posso ancora anticipare nulla. Forse al prossimo Salone del Mobile si vedrà qualcosa. Sono curioso di lavorare coi processi industriali. L’industria, a mio avviso, è entrata in un cul de sac, perché non si è aperta a processi nuovi e non ha le idee chiare. Spesso approccia un designer senza avere presente cosa commissionargli, pescando nel buio delle sue proposte. L’industria non ha tempo da dedicare al processo creativo e senza di quello non c’è spazio neanche per le idee nuove.

Una domanda a Mollino?

Perché non hai mai insegnato?

Una domanda a Gio Ponti?

Se ai tuoi tempi io avessi tagliato le sedie di Mollino, mi avresti dato spontaneamente i tuoi pezzi?

A proposito di insegnamento, tu hai insegnato per cinque anni al Royal College di Londra. Perché per un designer è così importante l’insegnamento?

Quando insegni non sei più tu al centro dell’attenzione. Devi spogliarti di tutto il tuo bagaglio, delle tue convinzioni, per aiutare gli studenti a capire cosa sia il design, indirizzandoli secondo la loro attitudine. Gli studenti sono molto critici e dalla critica s’impara. Per sviluppare l’idea di un altro hai bisogno di molta flessibilità.

La Trattoria al Cappello, progetto di un ristorante nomade e multidisciplinare, nasce dalla collaborazione con i grafici Maki Suzuki, Kajsa Stahl e Alex Rich, compagni di college. Mi racconti come è nata l’idea e la realizzazione di questo progetto?

A Londra i ristoranti sono troppo cari o non di qualità, e a noi è sempre piaciuta la buona cucina. Spesso organizzavamo delle cene insieme ad amici. Da lì è nata l’idea di mettere insieme i nostri lavori e la nostra passione, e così abbiamo deciso di organizzare una volta al mese un happening in cui progettavamo tutto, dal menu agli arredi, cucinando per un numero limitato di persone. Gli invitati non erano mai solo amici, si aggiungevano anche sconosciuti, chiunque rispondesse per primo all’invito lanciato via mail aveva un posto prenotato.

Da dove viene il nome Trattoria al Cappello?

Hattonwall è il nome di una strada nell’East End di Londra. Lì c’era un bar gestito da amici, Hat on Wall, semi-legale, con solo un bancone: è lì che sono avvenute le prime dieci cene.

Le tue cene, veri e propri happening, hanno sempre una combinazione magica di arte, cibo e amicizia?

Sì, per gli ospiti sì. Cerchiamo sempre di trovare la combinazione giusta, sperimentando qualche novità, ma c’è sempre qualcosa che sfugge. È capitato che gli ospiti non si amalgamassero tra loro, d’altronde spesso sono estranei che si ritrovavano allo stesso tavolo…

Una volta hai detto che il processo progettuale è simile a quello culinario. Parli del connubio tra idea e casualità?

In cucina si lavora con gli ingredienti, così come nel design si parte dai materiali. Si ha a che fare continuamente con la casualità perché si lavora col calore, si prendono decisioni immediate, non c’è tempo per pensare. Questo accade anche nel mio laboratorio. Non sempre il piatto è perfetto, ma c’è comunque qualcosa di interessante per cui vale la pena assaggiarlo. Conosco il mondo della cucina, da studente ho lavorato come cuoco, aiuto cuoco e cameriere, per mantenermi. Nella mia famiglia alcuni zii hanno attività, come pensioni e agriturismi. I miei stessi genitori sono contadini, quindi conosco la materia prima “cibo”. Quello che cerco, però, non è entrare nella logica del ristorante: voglio sperimentare, guidato dalla curiosità. Per me, ha più valore lo stare insieme, pongo l’accento sull’aspetto sociale.

![Trattoria al Cappello, London, 2009. Martino Gamper, Maki Suzuki e Kajsa Stahl]()

Trattoria al Cappello, London, 2009. Created by The Trattoria Team: Martino Gamper, Maki Suzuki and Kajsa Stahl. Photo: Amit Lennon

Il tuo piatto preferito?

Pasta allo zenzero, una mia ricetta.

Nel 2004 ho lavorato a un workshop con Rirkrit Tiravanija dal titolo No Vitrines, No Museums, No Artists. Just A Lot of People, organizzato da Domus Academy. La performance della trattoria mi ricorda lo spirito sottile dei suoi interventi. Rirkrit ha creato delle situazioni in cui spontaneamente le persone socializzavano, e spesso questo accadeva intorno ai fornelli. Il suo lavoro abbandona l’individualismo per aprirsi al pubblico, non più spettatore ma protagonista. Potrebbe essere il filo conduttore delle tue opere?

Sì, coinvolgere le persone fa parte della storia della gente di montagna. Culturalmente, sono abituato a invitare. Sono molto legato al contesto in cui nasce un progetto, alla committenza o al destinatario, e a ogni elemento del processo. Voglio seguire ogni passo, in ogni oggetto che creo c’è un pezzo di qualcuno, non solo perché utilizzo oggetti già vissuti, ma perché ciascun oggetto nasce con un destino già condiviso.

Il tuo è un lavoro volutamente ecologico? Si parla soprattutto di riciclo…

Sì, ma non amo il termine riciclo, ha una valenza tipica della qualità scadente: dopo il riciclo, il materiale non è mai al meglio delle sue possibilità. In inglese, c’è il termine recycling e upcycling, cioè dargli un altro ciclo, un’altra vita. La sedia per strada che nessuno desidera più ha un valore nullo; darle un’idea e includerla in una delle mie sculture significa rivalutarla. Più che di riciclo, oggi sarebbe meglio parlare di sostenibilità. Bisogna pensare e creare affinché le cose abbiano una vita più lunga. L’ecologico, se basato sul puro riciclo, dura ancora meno e supporta l’idea di un sistema debole e consumistico. Una sedia non dovrebbe costare 30 euro, dovrebbe costare molto di più e durare una vita intera. È vero che tutti possono comprare sedie oggi, ma alla fine siamo arrivati a una situazione assurda, in cui ognuno di noi potrebbe comprarsi una sedia al giorno… dovremmo invece riflettere sul perché il cibo costi così tanto e le sedie così poco…

Le tue opere sono pezzi unici o edizioni limitate, scelte più comuni all’ambito artistico… perché questa scelta?

Il motivo per cui non ho mai fatto edizioni industriali è semplice, ed è legato al mio metodo: il fatto di utilizzare oggetti già esistenti e di lavorarli manualmente, in laboratorio, non mi permette di abbracciare il processo industriale. L’edizione limitata è senza senso, esiste solo per mere questioni di mercato. Per esempio, la libreria Together, che ho prodotto in una edizione di 12 esemplari per la Galleria Nilufar di Milano, è un sistema che potrebbe essere riproducibile, ma non lo è perché è costituita da moduli componibili in diverse misure, quindi tutti diversi.

Le commissioni di alcuni lavori che hai realizzato provengono da colleghi e amici.

Il 70% del mio lavoro nasce liberamente, senza committenza, o con una committenza personale.

Hai sempre progettato in piccola scala, oggetti o interni: cosa ti affascina di più in questa dimensione?

Direi che questa scelta è piuttosto dettata dal fatto che non ho avuto altre occasioni. La grande scala non può essere eseguita da solo o in laboratorio.

Sei attratto dall’idea di progettare in scala maggiore? Certo, perderesti in gran parte la dimensione artigianale…

Sì, mi piacerebbe, ma non ho le competenze di un architetto. Devo dire che se potessi scegliere, mi interesserebbe di più progettare un edificio che un piano urbanistico.

Non sai stare fermo con le idee, sei un sognatore: da uno sgabello può nascere un dondolo e da un pallone da calcio una lampada. Mi dici qualcosa di più sulla tua idea di craftsmanship? Scusa l’inglesismo, ma “artigianalità” non rende l’idea tanto quanto il vocabolo inglese…

L’aspetto craftsmanship mi aiuta a esprimermi, se fossi bravo a disegnare non mi metterei a fare delle sculture. Perché dovrei fare qualcosa che sembri industriale? I difetti delle mie opere sono anche il loro pregio, le industrie non riescono a farlo. È il mio modo di distinguermi. Non è una strategia di marketing, ma quanto di più vicino al mio pensiero.

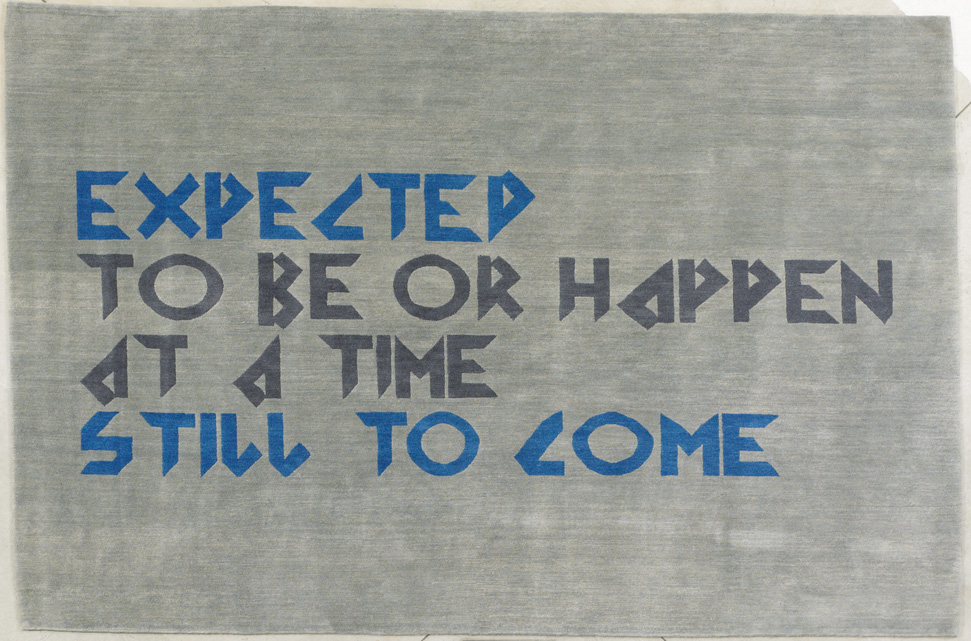

Per la Galleria Nilufar hai prodotto un tappeto, Carpet Future, eseguito e annodato in Nepal, su cui è scritto a caratteri cubitali: Expected to be or happen at a time still to come. Che significato ha per te questa frase?

È un pezzo commissionato da Design Miami/Basel nel 2008, in occasione della selezione Designers of the Future, in cui sono stati presentati quattro designer. Questa è la mia interpretazione del futuro: aspettarsi il momento che dovrà venire. Il font che ho scelto di usare per la frase è tipico della science fiction degli anni Settanta, quando il futuro aveva ancora una visione fantastica.

![Martino Gamper, Carpet Future, 2008. Courtesy: Galleria Nilufar, Milano]()

Martino Gamper, Carpet Future, 2008. Courtesy: Galleria Nilufar, Milano

Cosa è cambiato rispetto alla visione del futuro di trenta anni fa?

Oggi abbiamo una visione più disincantata del futuro. Il tempo passa veloce, ma il nostro mondo non cambia altrettanto velocemente. A Londra continuiamo a vivere nelle case vittoriane e non ci immaginiamo su astronavi. L’attrazione per il fantascientifico è stata sostituita dal trend del vintage. Insomma, il futuro andrà più lentamente di quanto ci immaginavamo trent’anni fa. Gli unici interrogativi seri da considerare sono: come potremo vivere su questo pianeta senza risorse e con i cambiamenti climatici che hanno già avuto effetti disastrosi?

Parlami del tappeto come oggetto.

Il tappeto mi interessa perché è stato totalmente sottovalutato dal design contemporaneo. Non mi soffermo solo sulla veste grafica: il pavimento come elemento progettuale è fondamentale quanto il tavolo o la sedia. In Oriente, il tappeto è il più nobile degli oggetti domestici, veniva utilizzato per tramandare storie; in Occidente invece ha perso completamente la valenza narrativa, diventando un oggetto puramente decorativo.

Quali sono i tuoi riferimenti storici nel design e nell’arte?

Tanti e nessuno. Per fare alcuni nomi: Franco Albini, Dino Gavina, Carlo Mollino, Gio Ponti, Ettore Sottsass, ma anche Mathieu Mategot, Charlotte Perriand, Jean Prouvé. Alcuni dei miei professori come Ron Arad ed Enzo Mari. E tra gli artisti, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Gianni Colombo e Martin Kippenberger. Sono libero, non li guardo.

Sei ossessionato dagli angoli. È una ossessione che si ritrova in molti tuoi progetti: da quelli pubblici, come Berlino Bench (2004) e The Book Corner (2002) per il British Council, ad altri come Sit Together Bench (2000), Totem Shelf 01 (2000), Booksnake Shelf (2002), i vari Corner Lights (2000-2003), fino al Kid’s Corner (2002). Cosa rappresenta per te questo elemento? È una sfida o un vecchio compagno di viaggio?

Sicuramente, un vecchio compagno di viaggio. Già la mia tesi al college analizzava l’angolo come elemento progettuale. L’angolo è un elemento che riguarda l’interno di uno spazio. Gli architetti non vi si soffermano molto e i designer ne hanno timore. Tutte le stanze hanno angoli irrisolti e quindi mi piace pensare l’angolo come elemento d’incontro tra il mobile e l’architettura. Poi c’è anche un discorso sociale: al di là della sua geometria, gli angoli sono posti che ti fanno sentire sicuro, sono luoghi solitari dove rifugiarsi e pensare. Allo stesso tempo, possono essere claustrofobici o isolati, basti pensare a modi di dire come: l’angolo più sicuro della casa o mi hanno messo all’angolo. È contraddittorio, ma ha un grande potenziale.

Mi racconti un’idea che non hai mai realizzato? Potrebbe essere uno scoop, un sogno da raccontare o magari un appello…

Una valigia. Non trovo una valigia che mi piaccia e che sia funzionale. Mi piacerebbe pensarne una.

Il progetto più importante per te?

100 Chairs in 100 Days and its 100 Ways.

Il progetto di cui ti sei pentito, se c’è?

Tanti piccoli che non avrei voluto fare, ma non li ricordo neanche.

Un’occasione persa e un’occasione presa al volo?

Perse ce ne sono tante… presa al volo, quella di realizzare una sedia industriale.

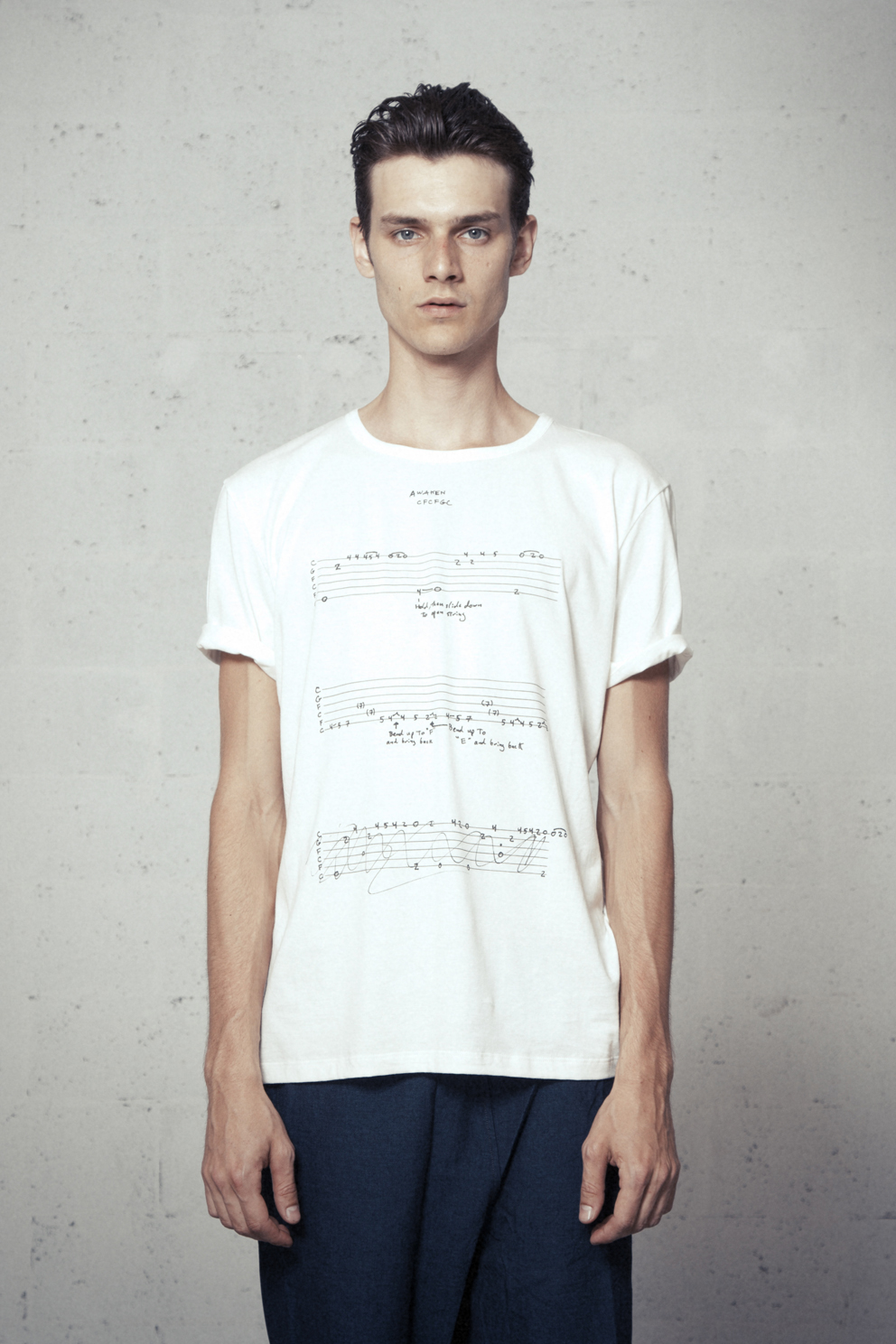

![Martino Gamper, Cover Version’s, 2009. Photo: Anna Arca]()

Martino Gamper, Cover Version’s, 2009. Photo: Anna Arca

Oltre a te stesso, c’è qualcuno a cui devi molto del tuo successo?

Tante persone: gli amici soprattutto, lo studio Åbäke, mia moglie, la Galleria Nilufar, la mia famiglia e i miei maestri.

Magari da piccolo ti piacevano i Lego… come hai trasportato l’infanzia o il passato nel lavoro?

La vita in montagna è diversa da quella in città: anche se mi fossero piaciuti, i videogiochi non esistevano. Passavo le giornate mettendomi sempre ad aiutare gli altri, a cucinare, a fare i loro mestieri. Mi piaceva molto aiutare la gente.

Ti sei sposato da poco… pensi che questa nuova vita ti cambierà?

È già cambiata… in positivo certo, vivo una vita diversa. Lavoro un po’ di meno e questo giova anche la mia attività. Vorrei essere meno egoista. Io e mia moglie lavoriamo insieme: lei è un’artista, ci siamo conosciuti perché voleva coinvolgermi in un progetto, e da lì è nata la storia. Lei aiuta me e io aiuto lei.

Cosa manca al design di oggi?

Al design di oggi manca la riflessione sull’oggetto come qualcosa che duri nel tempo, che invecchi bene. Enzo Mari lo ha sempre detto. Purtroppo, essendo noi tutti un po’ vittime della moda e dei trend, si progetta pensando a un ciclo di vita dell’opera molto breve. Abbiamo noi stessi la paura di invecchiare male e direi anche del tempo che passa.

Secondo te, una volta era più facile essere conosciuti?

Il mondo dei media è veloce, ti offre molte più possibilità rispetto a prima, ma ti dimentica altrettanto velocemente. Tutti hanno fretta di diventare ricchi

e famosi. Credo che questo atteggiamento generi un approccio sbagliato alla vita. Trovo più interessante sviluppare un pensiero senza l’assillante ricerca

di notorietà. Sarà poi il tempo a giudicare…

/

In response to great demand, we have decided to publish on our site the long and extraordinary interviews that appeared in the print magazine from 2009 to 2011. Forty gripping conversations with the protagonists of contemporary art, design and architecture. Once a week, an appointment not to be missed. A real treat. Today it’s Martino Gamper’s turn.

Paolo Priolo

Interview by Laura Garbarino. Klat #02, spring 2010.

Martino Gamper, one of the most intriguing personalities in the world of contemporary design. Ron Arad has called him «a wizard, an inventive chef», while his friend the graphic artist Kajsa Stahl says he’s a «last-minute perfectionist». His method has something brilliant about it, ranging from crafts to improv to the conceptual. In all his projects, at dinner with friends,

in all his various theories, spontaneity and uniqueness

are his most outstanding traits.

Hi Martino. To define yourself, in what order should we list these terms? Designer, artist, chef…

As a profession I think of myself as a designer, but my approach to design is artistic, in certain ways. Like an artist, I can work without having a client. Not having a client can be a good thing, because you are freer, but the void can be scary too. My method has a lot to do with research, and less to do with creation, which is sort of the difference between a designer and an artist. The two spheres are set apart by the functional aspect. Art can be irrational, it doesn’t have to explain anything. On the other hand, I have to be able to define what I create and above all I want my sculptures, my objects, my furniture to be used. So to answer your question: designer, craftsman, artist and chef.

Italian by birth: Merano, 1971. Londoner by choice: you studied at the Royal College and then stayed in England. Why London?

London, first of all, for training. I escaped from Italy when I was quite young. After working as an apprentice with a carpenter, when I was 19 I left the mountains, and Italy, to explore the world. I felt isolated in the place I grew up. I love the mountains, but they don’t let you see what’s happening on the other side of their peaks.

Between Merano and Milan, where you gained experience during two years in the studio of Matteo Thun, there was the Academy in Vienna and many trips to different places in the world. I think that living in different cities, moving your thoughts in the world, has a decisive influence on a person’s character and way of being. What did you get from Vienna and the nomadism of your travels?

Vienna influenced me, it offered the great culture of Humanism, the start of crafts design, the Jugendstil, the Secession, but also the art in the 1970s and 1980s, Viennese Aktionismus, the culture of food and coffee. The experience in the studio of Matteo Thun was my first contact with industrial design. It was a useful, engaging, educational experience, because the world of work is hard to understand for someone who just got out of the academy or the university. I’d say that Thun taught me a method, but he also showed me what I didn’t want to do, helping me to find my own path, my own dimension, making me aware that I didn’t want to work for someone else, but only for myself. Before studying in Vienna I traveled around the world for two years: the United States, Central America, Guatemala, Mexico, Hawaii, New Zealand, Australia, the Philippines, Thailand. Every one of those places left me with something, it would take too long to list them all, but they all had a part in making me what I am today.

How did you choose your destinations?

I had a “round the world” airline ticket that lets you stop wherever you want, as long as you continue moving in the same direction, never backtracking, so at times the choices were obligatory. What did I learn from that trip? That the world is full of possibilities, and you are the one that has to choose. The world doesn’t make choices for anyone, when you travel you have to make a choice every day, about where to go and how long to stay there.

![Martino Gamper, 100 Chairs in 100 Days and its 100 Ways, 2005-2007. Photo: Åbäke, Martino Gamper]()

Martino Gamper, Omback, 100 Chairs in 100 Days and its 100 Ways, 2005-2007. Photo: Åbäke, Martino Gamper

What does Italy mean to you? How do you see it, now that you live elsewhere?

Italy remains a point of reference, with my home, my family, a certain sense of belonging. From abroad, you can’t really understand what is happening in Italy, the media seem to only talk about superficial things or scandals, and it seems like the Italians can identify with this culture of appearances, void of meaning, tired. Actually, I think the mentality of young Italians has opened up in recent years, in search of a change the country doesn’t offer. They are starting to travel more and many of them, first by necessity and now also by choice, are looking for opportunities abroad.

What do you read to stay informed?

I read the New Yorker, the German weekly Zeit and every day I look at the BBC online, but I also visit the sites corriere.it, repubblica.it and stol.it, a Merano-based site, so I go from the world to Italy, my country.

Do you think you will ever return to Italy?

Not to live, at least for now, but there are many situations that take me there: vacations with friends, and work opportunities. And I am glad.

100 Chairs in 100 Days: your biggest show, which went from London to the Milan Triennale. The exhibition illustrates your creative capacities. Each seat has its own personality, they seem like portraits, three-dimensional collages. When I saw it I had the impression that you had infinite combinations available, to reach the design of each chair. How did you choose certain combinations instead of others? Was there an immediate creative impulse that guided you in the choice of the combinations?

The 100 chairs are finished projects, but those ideas have led to an equal number of others. The time limit made the project intriguing. I really did make them in 100 days, though not consecutive days, obviously. I enjoyed translating my ideas into a three-dimensional space, creating a sort of sketchbook.

Tell me about the titles you gave to each seat. Are they spontaneous or do they contain a key of interpretation?

I was asked to give them titles only when I began to do the catalogue for the show, so they came a posteriori. In some cases all I could do was associate the chairs with persons, humanizing them, though I had not previously thought about them as portraits. In other cases I wanted to be ironic about historical references or fantasy characters, like Barbapapà in Vienna, Sonet Butterfly or Charles and Ply.

When you start to work, assembling two chairs, do you already have an idea in mind about the result? I saw a video on YouTube, the making of aradson, showing you and one of your staff, Harry, in the design phase. You’re losing the initial idea sketched on the table with a pencil, and then at a certain point you say: «I want to save it». What did that mean, in that precise moment?

It’s easy to find a type of chair on which to start working, but if I don’t manage to finish I get stuck, so I move on to something else, and then go back to the work later. I’m not so tied to the starting point, but when I’m working on a prototype I have to at least try to complete that initial idea. In the case you saw in the video, I wanted to save the first idea, but in the end the result was different from what I previously had in mind…

Your way of working gives new life to forgotten objects, and at the same time it sacrifices the lives of objects that have made history, furniture by Gio Ponti or Carlo Mollino. Is this an attempt at interaction or reinterpretation of those works, or is it a matter of irreverence with respect to certain great masters?

I think that to create something new you have to deconstruct what exists or forget the past. I believe it is hypocritical and wrong to imitate a master or to want to become a new Ponti. For me, it is important to “cut up” what already exists: I do it respectfully, I see it as a sort of process of knowledge. I don’t have to start with pure raw material. Even something that has already been worked or utilized, and has its own form, can be seen as raw material from which to make another object. It’s not a question of “too much respect”, but of the evolution of thought. Excessive respect can hold you back. In the first performance I did at Design Miami/Basel, in 2008, If Gio only knew, I used the furnishings of the Hotel Parco dei Principi in Sorrento, designed by Gio Ponti. I felt hesitant, hampered by a form of excessive reverence. At the tenth work I let myself go, gripped by the enthusiasm of changing the fate of those objects. I thought that actually there was not much of Ponti in those furnishings, they were produced in a series, industrial, for a hotel. I didn’t want to destroy Ponti because he’s Ponti. There was certainly an element of provocation, and it is no coincidence that I chose to do the performance at Basel, because at a fair that defines itself as a fair of contemporary design most of the stands were offering Gio Ponti and design from the 1950s and 1960s. I didn’t see any space for young designers…

Speaking of the design market, what do you think about Ron Arad and Marc Newson, two of today’s contemporary design stars? Are they still designers or are they artists?

I’m a bit perplexed, not so much about their identity as designers, as about the fact that we’re talking about design or the market. Ron Arad was my professor in London and Vienna, I admire him very much. One day in class he said: «I will make the first chair you cannot sit on». From that point on, for me it was no longer design. Ron wanted to shock the design world and the market. He wanted to choose for the market out of fear that the market would choose for him, reaching the point of almost controlling him.

![Martino Gamper, Robot Chair, 2008. Courtesy: Galleria Nilufar, Milano]()

Martino Gamper, Robot Chair, 2008. Courtesy: Galleria Nilufar, Milano

You’ve never done industrial productions?

That question comes at the right time. I’m just about to do my first industrial production, though I can’t announce anything here. Maybe you’ll see something at the next Salone del Mobile. I am curious about working with industrial processes. The industry, in my view, has entered a cul de sac, because it has not opened up to new processes and it doesn’t have clear ideas. It often approaches a designer without knowing what to commission him to make, just fishing for proposals. The industry doesn’t have time to devote to the creative process, but without it there can be no room for new ideas.

Something you’d like to ask Mollino?

Why didn’t you ever teach?

A question for Gio Ponti?

If I had cut up Mollino’s chairs back in your day, would you have spontaneously given me your pieces?

Speaking of teaching, you have done it for five years at the Royal College in London. Why is teaching so important for a designer?

When you teach you are no longer the center of attention. You have to shed all your baggage, your convictions, to help students to understand what design is, guiding them in the direction of their talents. Students are very critical and you can learn from criticism. And to develop the ideas of others, you have to be very flexible.

The Trattoria al Cappello, a project for a nomadic, multidisciplinary restaurant, comes from your collaboration with the graphic designers Maki Suzuki, Kajsa Stahl and Alex Rich, all classmates from college. How did the idea come about, and how was it put into practice?

In London restaurants are too expensive, the quality is low, and we’ve always liked good food. We often organized dinners together with friends. That led to the idea of putting our work and our passion together, so we decided to organize a happening once a month in which we would design everything, from the menu to the furnishings, cooking for a limited number of guests. The guests were never only friends, we would also add some people we didn’t know. The first people to respond to an invitation sent out by e-mail would have a reservation.

Where did the name Trattoria al Cappello come from?

Hattonwall is the name of a street in London’s East End, and there was a bar there run by friends, the Hat (Cappello) on Wall, a semi-legal place with just a counter: that’s where we held the first ten dinners.

Do your dinners – veritable happenings – always have a magical combination of art, food and friendship?

Yes, for the guests. We always try to find the right combination, experimenting with new things, but something always eludes us. Sometimes the guests don’t make a good mix, often they are strangers, and they find themselves sitting at the same table…

![Trattoria al Cappello, London, 2009. Da un'idea di Martino Gamper, Maki Suzuki e Kajsa Stahl.]()

Trattoria al Cappello, London, 2009. Created by The Trattoria Team: Martino Gamper, Maki Suzuki and Kajsa Stahl. Photo: Amit Lennon

You once said that the design process is like cooking. Could you tell me about the connection between ideas and chance?

In the kitchen you work with ingredients, and in design you start with materials. You constantly have to deal with chance, because you work with heat, you have to make quick decisions, there is no time to think. That also happens in my workshop. The dish doesn’t always come out perfect, but there is still something interesting that makes it worth tasting. I know the world of cooking, when I was a student I worked as a cook and a waiter, to make ends meet. In my family some of my uncles have businesses, like guesthouses and rural tourism facilities. My parents are farmers, so I know about the raw material of food. What I want, though, is not to get into the logic of a restaurant: I want to experiment, guided by curiosity. For me socializing has more value, I put the accent on that.

Your favorite dish?

Pasta with ginger, my recipe.

In 2004 I was involved in a workshop with Rirkrit Tiravanija entitled No Vitrines, No Museums, No Artists. Just A Lot of People, organized by Domus Academy. The performance of the trattoria reminds me a bit of the subtle spirit of his works. Rirkrit has created situations in which people spontaneously socialize, often around a hot stove. His work abandons individualism and opens up to the audience; the viewers are no longer spectators, but players. Could that also be a leitmotiv of your works?

Yes, involving people is a part of the heritage of mountain people. Culturally, I’m used to inviting. I am closely tied to the context in which a project begins, the client or the person it is for, and every element of the process. I want to pay attention to every step, in every object I create there is a piece of someone, not just because I use objects that have already been experienced, but also because they are born with an already shared destiny.

Is your work intentionally ecological? There’s a lot of talk about recycling, above all…

Yes, but I don’t like the term recycling, it has connotations of poor quality: after recycling material is never at its best, never retains its fullest potential. In English, there are the terms recycling and upcycling, another cycle, another life. The chair you find on the street, that no one wants, has no value, so giving it an idea and including it in one of my sculptures means revaluation. More than recycling, it would be better to talk about sustainability today. We need to think and create so that things will have a longer life. Ecological things, if they are based on pure recycling, last even less, so they reinforce the idea of a weak system of ongoing consumption. A chair should not cost 30 euros, it should cost much more and last a lifetime. It is true that everyone can afford to buy chairs nowadays, but in the end we’ve reached an absurd situation in which each of us could buy himself one chair a day. Instead, we should think about why food costs so much and chairs cost so little…

Your works are one-offs or limited editions, choices more common in the art world… why?

The reason why I have never done industrial productions is simple, and it is connected with my method: the fact that I use objects that already exist and manipulate them, in the workshop, prevents me from using the industrial process. The limited edition makes no sense, it only exists for the market. For example, the Together bookcase, which I made in an edition of 12 pieces for the Nilufar Gallery in Milan, is a system that could be reproduced, but it is composed of modules of different sizes, so all the pieces are different.

The commissions for some of your works come from colleagues and friends.

About 70% of my work happens spontaneously, without a client, or from a personal commission.

You have always worked on a small scale, with objects or interiors. What fascinates you about that dimension?

I’d say that choice is dictated by the fact that I have not had other opportunities. You can’t work on a large scale by yourself, or in the workshop.

Are you attracted by the idea of working on a larger scale? Of course that would mean losing much of the crafts approach…

Yes, I would like it, but I don’t have the expertise of an architect. I must say that if I could choose, I’d be more interested in doing a building than an urban plan.

You are always restlessly looking for new ideas, and you’re a dreamer: a stool can lead to a rocking chair, a football can lead to a lamp. Would you tell me something about your idea of craftsmanship? That’s a word that works best in English…

The aspect of craftsmanship helps me to express myself, if I was good at drawing I wouldn’t make sculptures. Why should I do something that looks industrial? The defects of my works are also their beauty, industry can’t do that. It’s my way of standing out. It is not a marketing strategy, but something very close to my way of thinking.

For the Nilufar Gallery you produced a carpet, Carpet Future, made by hand in Nepal, bearing the inscription Expected to be or happen at a time still to come. What does that phrase mean to you?

That was a piece commissioned by Design Miami/Basel in 2008, for the selection Designers of the Future, which presented four designers. It is my interpretation of the future: waiting for the moment that is still to come. The font I chose for the phrase is typical of Seventies science fiction, when the future was still a fantastic vision.

What has changed, with respect to the vision of the future of thirty years ago?

Today we have a more disenchanted vision of the future. Time passes quickly, but our world does not change so quickly. In London we go on living in Victorian houses and we don’t imagine ourselves in spaceships. The appeal of science fiction has been replaced by the vintage trend. In short, the future will be slower than what we imagined thirty years ago. The only serious questions to consider are: how will we be able to live on this planet without any resources and with climate changes that have already had disastrous effects?

Tell me about the carpet as object.

Carpets interest me because they have been totally undervalued in contemporary design. I don’t only concentrate on the graphics, the floor as a design element is just as fundamental as a table or a chair. In the Orient the carpet is the most noble of all domestic objects, it was used to pass on stories; in the Occident, on the other hand, it has completely lost its narrative value, and become a purely decorative object.

What are your historical references in design and art?

Many and none. To name a few names: Franco Albini, Dino Gavina, Carlo Mollino, Gio Ponti, Ettore Sottsass, but also Mathieu Mategot, Charlotte Perriand, Jean Prouvé. Some of my teachers, like Ron Arad and Enzo Mari. And, among the artists, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Gianni Colombo and Martin Kippenberger. I am free, I don’t look at them.

You’re obsessed by corners. It is an obsession found in many of your projects: from the public ones, like Berlino Bench (2004) and The Book Corner (2002) for the British Council, to others like Sit Together Bench (2000), Totem Shelf 01 (2000), Booksnake Shelf (2002), the various Corner Lights (2000-2003), all the way to the Kid’s Corner (2002). What does this element represent for you? Is it a challenge or an old traveling companion?

Definitely an old traveling companion. My college thesis was on the corner as a design element. The corner has to do with the inside of a space. Architects don’t pay much attention to it, and designers fear it. All rooms have unresolved corners, so I like to think of the corner as the place where furniture and architecture meet. Then there is also a social side: beyond their geometry, corners are places that make you feel safe, solitary places where you can seek refuge and think. At the same time, they can be claustrophobic, isolated… just think about certain expressions, “go stand in the corner”, “the safest corner of the house”, “he’s in my corner”. The corner is contradictory, but it has great potential.

Can you tell me about an idea you’ve never been able to put into practice? A scoop, a dream to tell, an appeal…

A suitcase. I can’t find a suitcase I like, one that is functional. I would like to invent one.

The most important project, for you?

100 Chairs in 100 Days and its 100 Ways.

The project you regret, if there is one?

Lots of little things I wouldn’t have wished to do, but I don’t even remember them.

An opportunity lost, an opportunity snapped up?

All kinds of lost ones… snapped up: to make an industrial chair.

Besides you, is there someone to whom you own much of your success?

Many people: my friends, above all, the Åbäke studio, my wife, the Nilufar Gallery, my family, my teachers.

![Martino Gamper]()

Photo: Maria Ziegelböck

Maybe when you were a child you liked Lego… how have you transported childhood or the past into your work?

Life in the mountains is different from life in the city: even had I wanted them, there were no video games. I spent my time helping the others, cooking, doing chores. I really liked helping people.

You recently got married… do you think this new life will change you?

It already has… in a positive way, of course, I live a different life. I work a bit less and that’s good for my activity too. I would like to be less egotistical. My wife and I work together: she is an artist, we met because she wanted to involve me in one of her projects, that’s how the story began. She helps me and I help her.

What is lacking in today’s design?

Design today lacks reflection on the object as something that lasts in time, and ages well. Enzo Mari has always said this. Unfortunately, because we are all fashion and trend victims, to some extent, design is done by thinking about a very short life cycle for the work. We too are afraid of aging badly, and I’d say

we are also afraid of the passage of time.

In your view, was it easier to get known in the past?

The world of the media is fast, it offers you many more possibilities than before, but it forgets you just as quickly. Everyone is in a hurry to become rich and famous. I believe this attitude generates a flawed approach to life. I think it is more interesting

to develop your thinking, without the tiresome pursuit of fame.

In the end, time will be the judge…

Follow Paolo Priolo on Google+, Facebook, Twitter

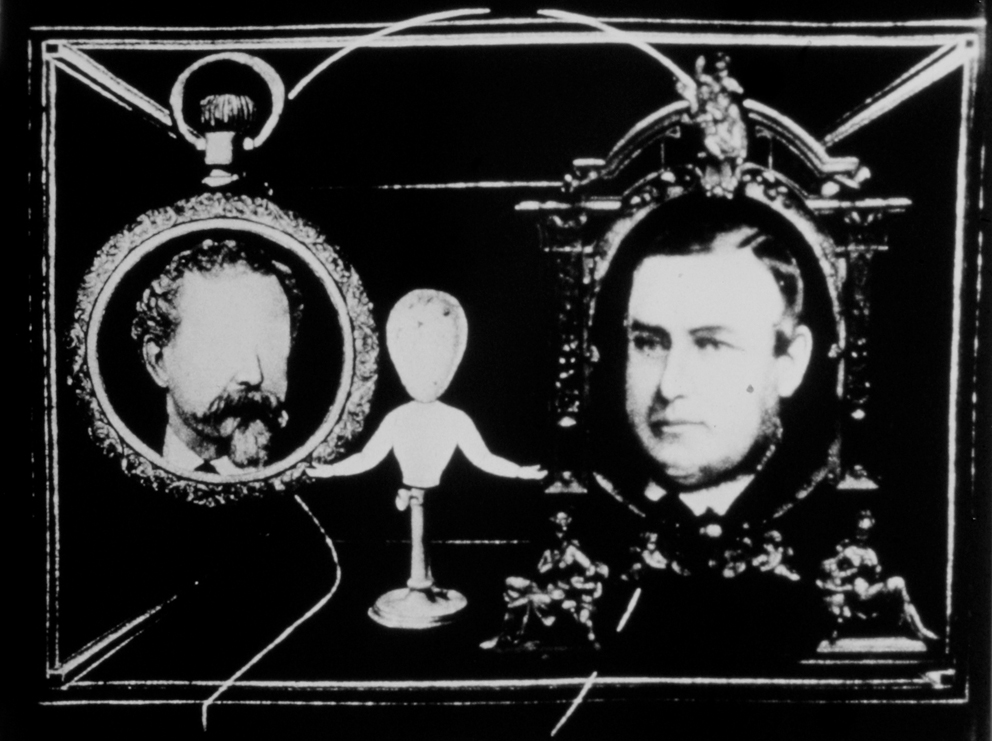

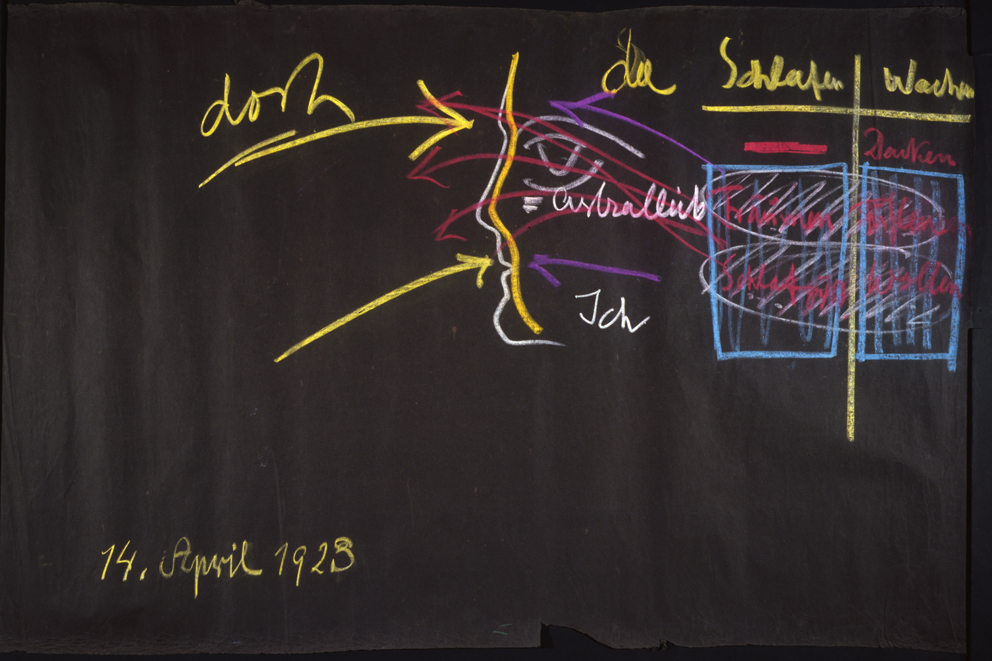

![Carl Gustav Jung The Red Book [page 655], 1915-1959](http://www.klatmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Klat_Carl_Gustav_Jung.jpg)